artwork by Nano Banana

Ontology - The Queryable Brain of Software Archaeology

Applied BMAD

Part 3 of 4Every seasoned developer knows the feeling. You inherit a complex, business-critical system where the original architects are long gone. There are multiple databases, a web of microservices, and the only documentation is a handful of outdated wiki pages. Your job is to add a new feature or fix a critical bug, but first, you have to answer a seemingly simple question: “If I change this, what breaks?”

The Legacy System Nightmare

This isn’t just a problem for decade-old monoliths. Consider the “Software Archaeology Tools Platform,” a production system that is only six months old. It already has eight microservices, three different databases (Neo4j, PostgreSQL, and Redis), 47 API endpoints, and 12 database tables with no clear ownership. To compound the issue, imagined if the team has already lost two of its three original developers, which is a 66% turnover rate, taking critical institutional knowledge with them. The new team is left trying to piece together how data flows through this intricate system.

There is a powerful way to cut through this complexity. By creating a formal semantic model of your system, an Software Archaeology Ontology (refer as SAR ontology in this article), you can build a “queryable brain” that holds a persistent, accurate, and discoverable map of its architecture and data flows. This post breaks down the five most impactful takeaways from applying this exact approach to the production system.

Consider this article is the missing puzzle piece of software archaeology, using BMAD-V6 SAR module to understand a legacy system, and BMAD-V6 ONTO module to document and analyze what has been done. Subsequently, the knowledge can be used to modernize the legacy system with strong evidence and confidence of impact.

Figure. The “Astronaut Pointing a Gun” meme is repurposed to illustrate the self-referential power of the Software Archaeology Tools Platform. This layered analysis establishes the Software Archaeology Ontology as the “queryable brain” for confident legacy system modernization, forming the completed puzzle of Software Archaeology.

Figure. The “Astronaut Pointing a Gun” meme is repurposed to illustrate the self-referential power of the Software Archaeology Tools Platform. This layered analysis establishes the Software Archaeology Ontology as the “queryable brain” for confident legacy system modernization, forming the completed puzzle of Software Archaeology.

1. You Can Literally Ask Your Codebase Questions

Traditionally, understanding data lineage is a painful, manual hunt. It’s an archaeology dig through unfamiliar code, outdated wikis, and the hazy memories of the last senior engineer who touched the code. It’s guesswork, not engineering.

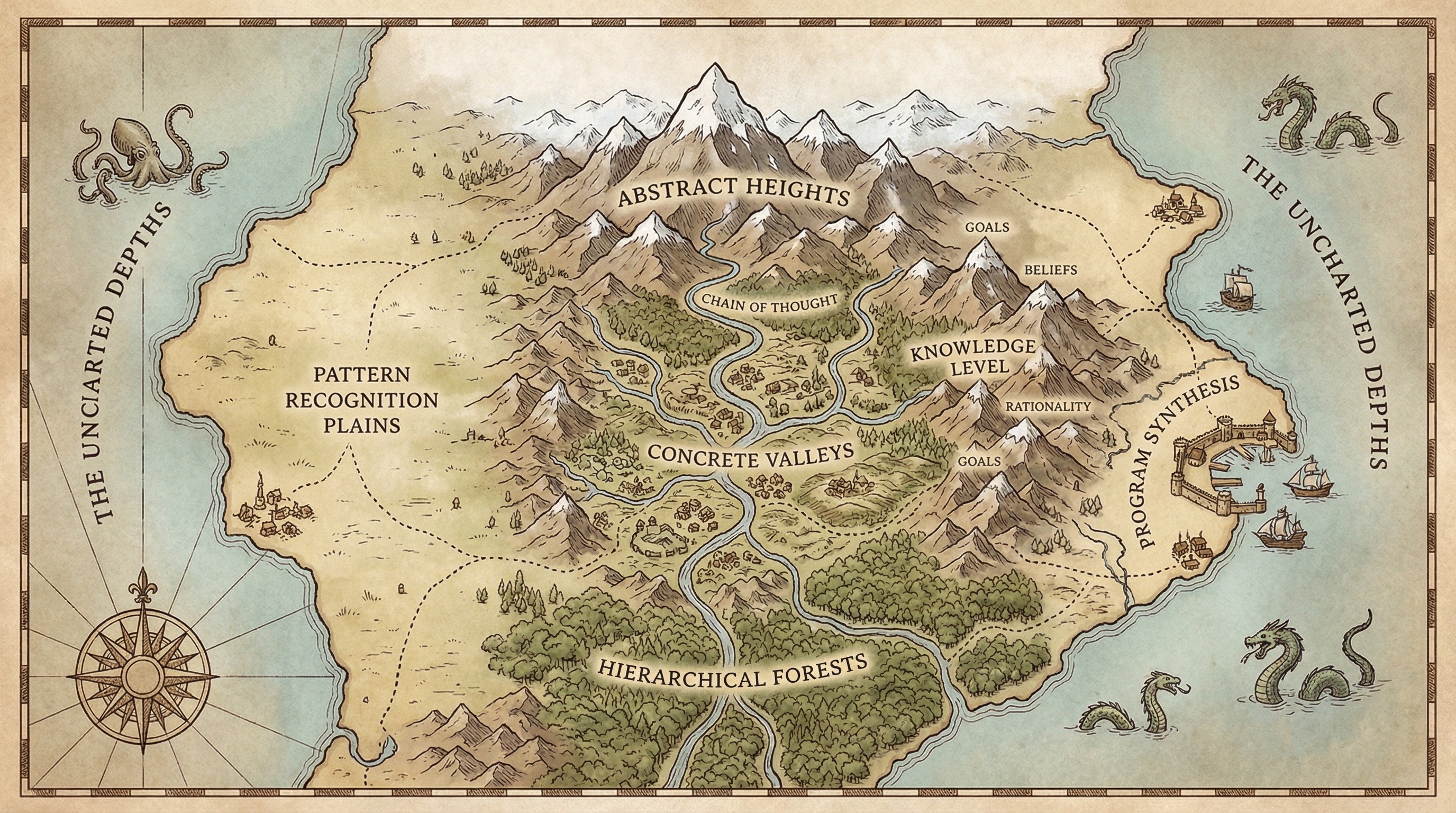

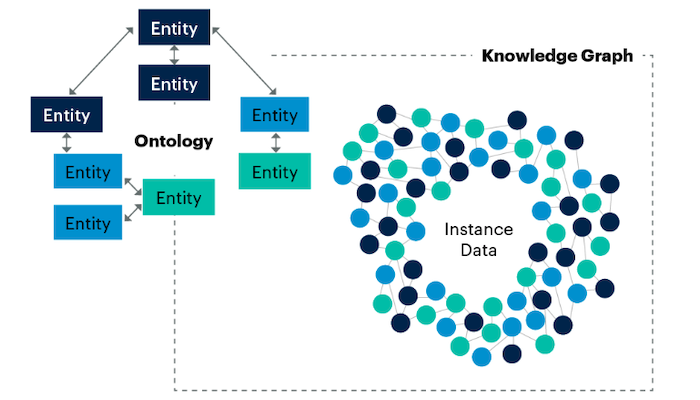

An ontology-driven approach shatters this paradigm. Instead of detective work, you get deterministic answers. By modeling the system’s components (e.g. services, APIs, databases, tables) and the relationships between them (e.g. dependsOn, calls, produces, writesTo), you create a knowledge graph. With this graph in place, you can use a query language like SPARQL to ask precise, complex questions and get definitive answers.

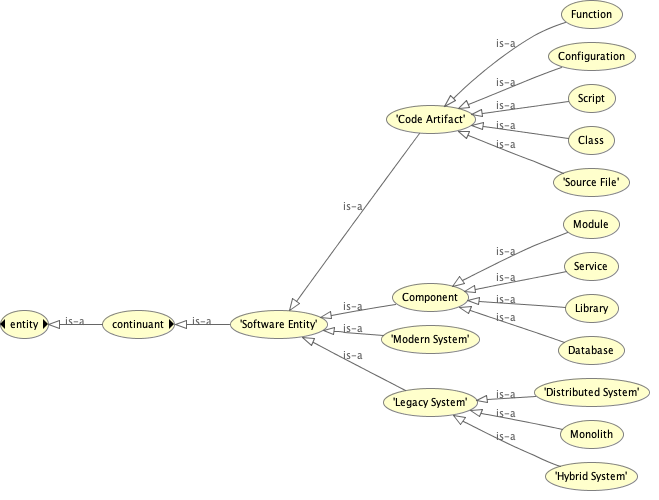

Figure. Illustrate the partial SAR Ontology modeling the Software Entity hierarchy. The ontology can be loaded into the popular Protégé platform for maintenance and visualization needs. We can also use Python programmatically manage and query the ontology, using rdflib or owlready2.

For example, instead of manual guesswork, you can now ask:

- “Which components have the most dependencies (coupling hotspots)?”

- “Which API endpoints write to which database tables?”

- “When a user interacts with the React UI dashboard, where is data stored?”

- “What technical debt items have the highest priority for remediation?”

Crucially, the answers to these questions are not hardcoded. They are discovered in real-time by tracing the relationships that have been formally modeled in the ontology. This turns system understanding from an art into a science. The beauty of this model is that even an incomplete answer is valuable. A query that returns nothing doesn’t mean the tool failed; it means you’ve discovered a gap in your knowledge model that needs to be filled.

Key Insight: The quality of data lineage tracing depends on how completely the system relationships are modeled in the SAR ontology. Gaps in the results indicate areas where the ontology needs enhancement.

From Ontology to Knowledge Graph Explained

The ontology serves as the blueprint or formal semantic model (or schema) that dictates the structure and relationships within a domain, defining concepts like Database and how it can relate to a Service using properties such as sar:dependsOn. In contrast, the knowledge graph is the actual data repository that holds the specific, real-world facts—the complete Software Archaeology Platform dataset in this case—which is represented as instance triples derived from and governed by the ontology schema.

Figure. Knowledge Graphs are machine readable data structures that represent knowledge of the physical and digital worlds as modeled in an ontology.

Therefore, the knowledge graph is built upon the ontology, combining the abstract structural definitions (the schema triples) with the concrete data (the instance triples). This combination allows complex operational tasks, such as automatically tracing complete data lineage across components using SPARQL queries against the knowledge graph, where the accuracy of the resulting lineage trace is directly dependent on how completely the system relationships were initially modeled in the SAR ontology.

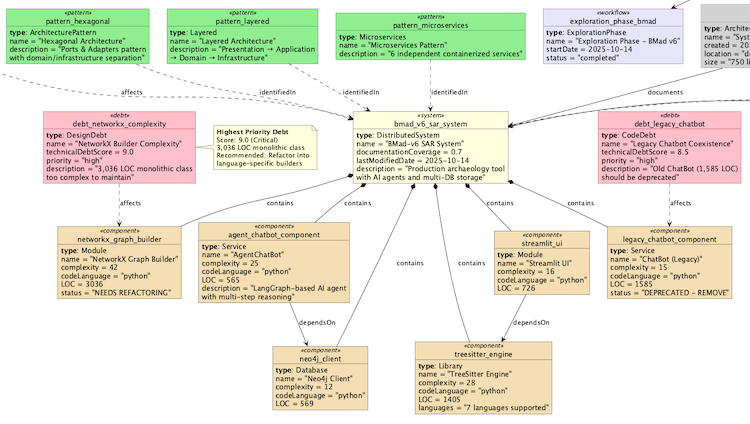

Figure. For example, real-world instance data from BMAD-V6 system exploration, showing the real components, technical debt items and architecture patterns identified.

2. Team Turnover Doesn’t Have to Be a Knowledge Black Hole

Team turnover is a critical business risk. When experienced developers leave, they take with them a wealth of undocumented knowledge about system architecture, design rationale, and operational quirks. As seen with the real system, losing two of its three original developers in just three months created a massive knowledge vacuum.

An ontology acts as a persistent, centralized knowledge base that mitigates this risk. It captures the essential “institutional knowledge” that is typically lost during team changes, formalizing it into a queryable model. The relationships between services, the purpose of different database tables, and the flow of data through workflows are no longer just in a developer’s head; they are explicit facts in the knowledge graph.

The impact on onboarding is dramatic. For our team, the time required to get a new developer productive was reduced from an estimated from weeks without the ontology to just days with it. This is because new team members can independently explore the system and answer their own questions, drastically reducing the ramp-up time and the risk associated with team churn. The system remains understandable and maintainable, independent of who is on the team today.

3. Impact Analysis Becomes a Science, Not Guesswork

This problem is magnified by the very team turnover we discussed. When institutional knowledge is gone, making changes to a complex system becomes a high-stakes guessing game. “If I modify this PostgreSQL table schema, what services will break?” Without a complete map, developers regress to grep-and-pray, hoping their text searches uncover every critical dependency. This isn’t a strategy; it’s a recipe for production incidents.

The ontology transforms impact analysis from guesswork into a deterministic process. In the scenario of changing a PostgreSQL schema, a single SPARQL query can be executed to find every single service, API endpoint, and component that depends on that database. The query returns a definitive list of affected components, eliminating all ambiguity.

This list becomes the foundation for a deterministic plan. You can even generate concrete effort estimates by assigning an average time per component, turning an ambiguous task into a quantifiable metric like “2.5 developer-days.” This capability transforms a multi-day exercise in high-anxiety guesswork into a one-hour task of precise, data-driven planning.

4. The Business Case Isn’t Soft - It’s Massive and Measurable

We’ve all struggled to justify time for “documentation,” a task often dismissed for its “soft” value. An ontology-driven approach reframes the discussion entirely, delivering a return on investment that is anything but soft.

For our system, an illustrative ROI calculation showed that the total annual value delivered by the ontology was ten of thousands dollars of labour saving, yielding an potential ROI of ~10x productivity, on an initial investment of just 20 hours for modeling and 10 hours for annual maintenance. This value comes from quantifiable time savings in common development activities, reduced onboarding costs, and the prevention of costly production incidents.

The estimated time savings on specific, recurring tasks are the most dramatic consideration of this value:

| Activity | Without Ontology | With Ontology |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding data flows | 2-3 weeks | 30 minutes |

| Finding all database consumers | 1 week | 5 minutes |

| Planning database migration | 2 weeks | 4 hours |

The key insight is simple: the more complex a system is, the higher the ROI will be for modeling it in an ontology. What took weeks of manual effort can now be accomplished in minutes with a single query.

5. Your System Documentation Can Finally Be Alive

The fundamental flaw of traditional documentation, whether it’s a diagram in a wiki or a Markdown file in a repository, is that it’s static (aka. dead). It becomes outdated almost the moment it’s written. Development moves fast, and documentation rarely keeps pace, quickly becoming a source of misleading or incorrect information.

The ontology approach creates a living document. It establishes a virtuous cycle where use drives maintenance. When an engineer runs a query to find a data lineage path and the query returns no result, it isn’t a failure of the tool. It is a clear signal that the system has changed and the model needs to be updated. The missing relationship is an explicit gap that needs to be filled.

This means that the very act of using the ontology for daily tasks, like performing impact analysis or onboarding a new developer, also serves to validate and maintain its accuracy. The model becomes an evolving asset that can grow with the system, starting with high-level architecture and gradually adding more detail over time, such as fine-grained, column-level data lineage, as the need arises.

Conclusion: Your System is Talking, Are You Listening?

This isn’t a theoretical exercise; it’s a practical, high-ROI discipline for taming the systems we build. By treating system knowledge as a first-class, queryable asset, we reclaim control over our architecture. The Software Archaeology platform shows that this is a practical approach for real-world production systems.

The legacy system nightmare isn’t inevitable; it’s a data problem. By giving our systems a queryable brain, we turn the nightmare of ambiguity into a dialogue with our own architecture. What is the one critical question about your legacy system’s data flow that no one on your team can confidently answer today?

References

- BMad Method - Foundations in Agentic Agile Driven Development, known as the Breakthrough Method of Agile AI-Driven Development

- [BMad Method User Guide](https://github.com/bmad-code-org/BMAD-METHOD/blob/main/docs/user-guide.

- Benny Cheung, BMAD V6 Intellectual Ecosystem for Understanding Legacy Software, Benny’s Mind Hack, 17 Oct 2025.

- Proposes the BMAD-V6 framework as a profound shift in thinking about AI, moving it from a reactive query tool to an integrated component within a complete intellectual ecosystem for systematic problem-solving. This philosophy, which includes a rigorous initial discipline of defining the problem and a collaboration between humans and AI, is specifically applied to the challenge of deconstructing, understanding, and resolving the intricacies of legacy software by turning chaotic, amorphous problems into bounded, addressable challenges.

- Benny Cheung, Unlocking the Secrets of Tabletop Games Ontology, Benny’s Mind Hack, 24 Feb 2025.

- Explores the development of an Ontology for Tabletop Games as a method for creating a consistent, formal, and discoverable representation of a complex, ambiguous domain. The effort highlights how constructing such an ontology moves beyond mere data organization, creating a semantic model that can be used to query, reason about, and generate new insights from the system’s architecture and logic.

-

Natalya F. Noy and Deborah L. McGuinness, Ontology Development 101: A Guide to Creating Your First Ontology, Stanford University.

- Protégé - is a free, open-source ontology editor and framework used to build intelligent systems, with a plug-in architecture for simple and complex applications.

Appendix - SAR Ontology

This ontology provides a formal semantic model for the Software Archaeology (SAR) domain, enabling systematic knowledge capture, integration, and analysis of legacy software systems. The ontology standardizes terminology across software archaeology activities, supports automated reasoning about system relationships, and facilitates knowledge transfer during brownfield development.

What is SAR Ontology?

An SAR Ontology is a formal, machine-readable model of knowledge that defines:

- Concepts (classes): What things exist? (e.g., LegacySystem, Component, Agent)

- Properties (relationships): How things relate? (e.g., dependsOn, executes, contains)

- Instances (individuals): Specific examples? (e.g., PaymentService, Dr. Ada Archaeologist)

- Axioms (rules): What constraints apply? (e.g., A Component can only belong to one Module)

At the high-level, the SAR Ontology is constructed like the following structure:

BFO (Basic Formal Ontology)

├── Continuant (Persistent Entities)

│ ├── Software Entities

│ │ ├── LegacySystem (kind)

│ │ │ ├── Monolith

│ │ │ ├── DistributedSystem

│ │ │ └── HybridSystem

│ │ ├── Component (kind)

│ │ │ ├── Module, Service, Library, Database

│ │ └── CodeArtifact (kind)

│ │ ├── SourceFile, Class, Function

│ ├── Agents (roles)

│ │ └── 6 agent types (Archaeologist, Cartographer, etc.)

│ ├── Quality & Patterns

│ │ ├── TechnicalDebt (mode)

│ │ ├── ArchitecturePattern (kind)

│ │ └── CodeSmell (mode)

│ └── Documentation

│ └── README, APIDoc, ArchitectureDoc, Runbook

└── Occurrent (Processes/Events)

├── ArchaeologyPhase (phase)

│ └── 5 phases (Exploration → Modernization)

└── Workflow (kind)

└── 5 workflow categories

SAR Ontology creates a semantic model for software archaeology:

- 96 Classes - Domain concepts (systems, agents)

- 23 Properties - Relationships (dependsOn, executes)

- 1,076 Triples - Rich knowledge graph

- 26 Competency Questions - Validated use cases

Here are many advantages to use SAR Ontology instead of tradition approach:

| Traditional Approach | Ontology Approach |

|---|---|

| Knowledge in people’s heads | Formalized knowledge graph |

| Documentation scattered | Single semantic model |

| Manual dependency tracing | Automated SPARQL queries |

| Tribal knowledge lost | Persistent, queryable knowledge |

| Siloed understanding | Shared vocabulary |