artwork by Gemini 3 Pro (Nano Banana Pro)

Abstraction of Thought Makes AI Better Reasoners

Chain-of-Thought made LLMs seem smart. But what if step-by-step thinking is the problem, not the solution? Human experts don’t just plow through problems sequentially. Instead, we build mental models, identify overarching principles, and sketch out strategies before diving into details. This article explores Abstraction of Thought (AoT), a structured reasoning format that explicitly incorporates multiple levels of abstraction, demonstrating how teaching AI to think at different levels of abstraction dramatically improves reasoning performance.

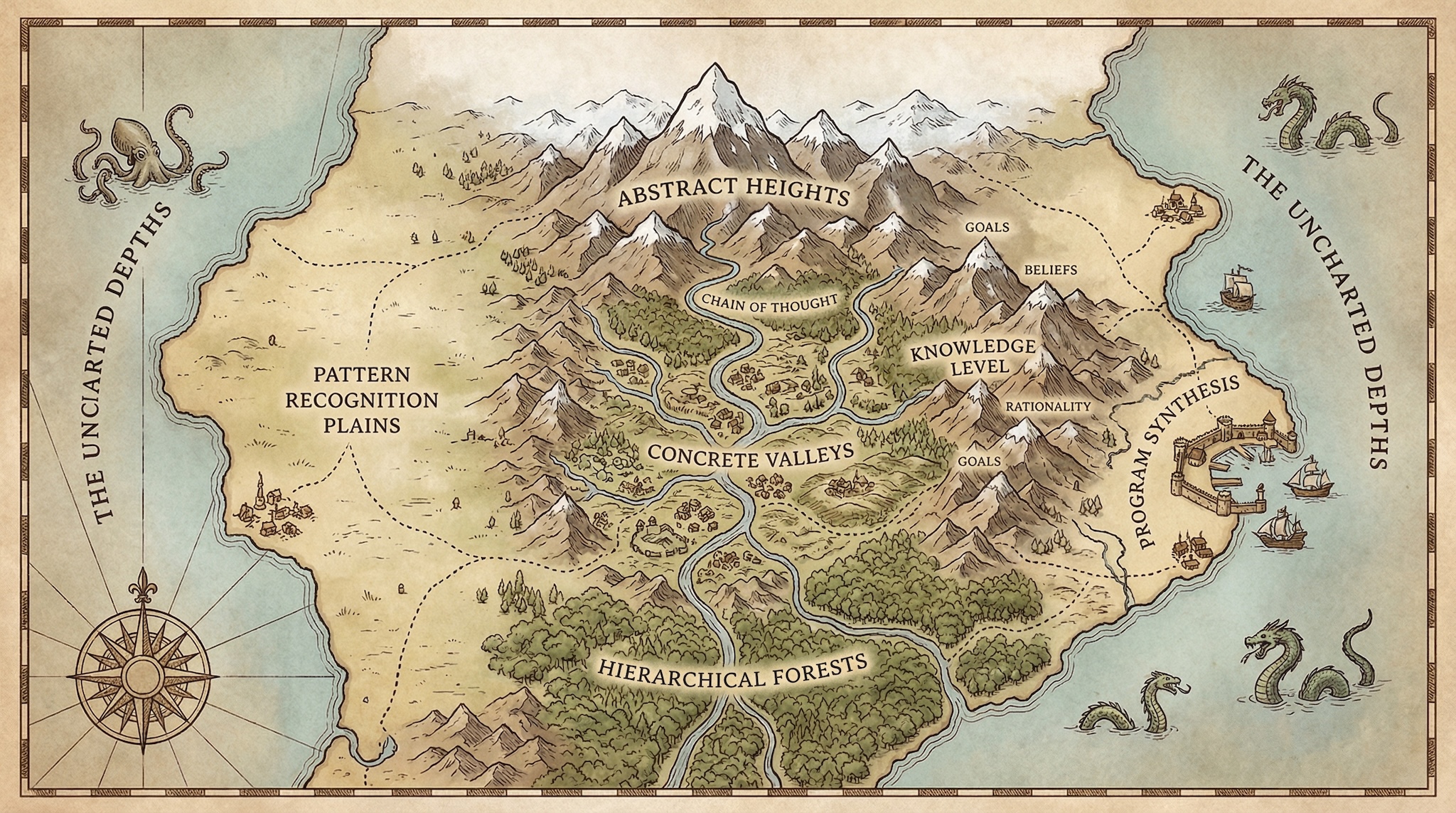

Figure. A cartographic abstraction of the reasoning landscape — from the “Abstract Heights” of high-level principles down through “Concrete Valleys” of detailed operations. Like explorers charting unknown territories, we navigate through “Hierarchical Forests,” cross “Chain of Thought” rivers, and venture into “The Uncharted Depths” where reasoning challenges await. This map serves as a metaphor for how abstraction organizes our exploration of complex problem spaces.

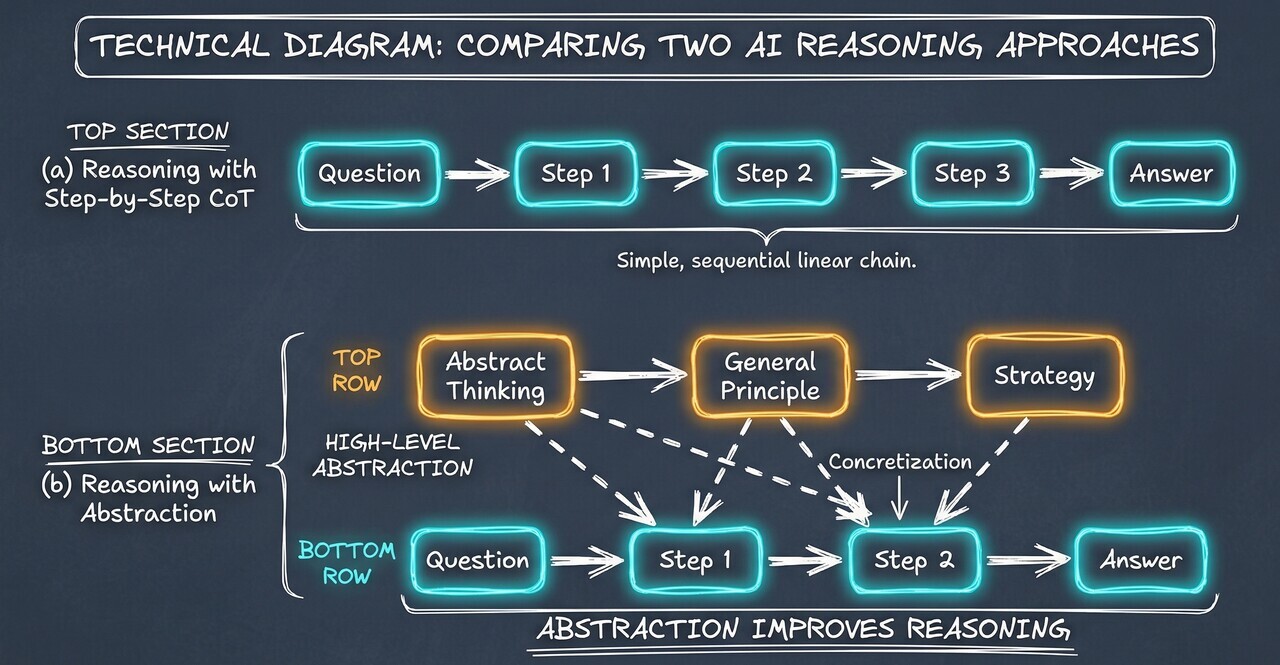

The quest to imbue Artificial Intelligence with genuine reasoning capabilities remains one of the most significant challenges, and opportunities, in the field. While Large Language Models (LLMs) demonstrate remarkable fluency and knowledge retrieval, pushing them beyond pattern matching towards deeper understanding and complex problem-solving requires fundamentally new approaches. Current techniques like Chain of Thought (CoT), Tree of Thoughts (ToT), and Graph of Thoughts (GoT) represent important strides, primarily focusing on enumerative or sequential exploration of reasoning steps. However, a crucial element often missing is the ability to think abstractly, a hallmark of human cognition when tackling complex problems.

This article closely aligns with ideas from recent research on Abstraction-of-Thought [1] while connecting it to foundational work on abstraction in AI [2] and the broader challenge of measuring intelligence through abstraction [3]. We shall explore how structured, multi-level abstract thinking could be the key not only to unlocking superior AI reasoning but also to making these powerful systems more understandable, reliable, and perhaps even controllable.

The Limitations of Linearity

Existing methods like Chain of Thought often encourage LLMs to generate a linear sequence of detailed steps. While effective for certain tasks, this approach can resemble plowing through a problem without first surveying the landscape. For truly complex challenges, human experts rarely operate this way. We build mental models, identify overarching principles, sketch out strategies, and then fill in the operational details. We leverage abstraction.

Figure. Reasoning with abstraction attempts to answer questions from the perspective of abstract essences, which may be overlooked by step-by-step Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning. The lower levels (blue nodes) perform concrete reasoning rich in detail, while higher levels (red nodes) are abstractions that organize the entire reasoning process.

Consider solving a quadratic equation, $ax^2 + bx + c = 0$. A purely sequential approach might immediately start substituting values. Abstraction-of-Thought, however, mirrors a more expert process:

- Abstract Level: First identify the type of problem: “This is a quadratic equation.”

- Strategic Level: Access the general principle for solving it: “The standard solution uses the quadratic formula: $x = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a}$.”

- Concrete Level: Only then proceed to substitute the specific values of a, b, and c.

This initial abstract identification provides a robust blueprint. The model isn’t just solving one equation; it understands the class of problems and the general method applicable to all instances of that class. This feels closer to genuine understanding than rote calculation.

What is Abstraction?

Before diving deeper into how abstraction improves AI reasoning, we need to understand what abstraction actually means. Far from being a dusty academic concept, abstraction is a vital, pervasive tool that shapes how we interact with the world, how we think, and how we build intelligent systems.

The word literally means “to draw away,” but its meaning has evolved. It’s not just about taking things away; it’s about purposeful simplification. As Goldstone and Barsalou put it, “To abstract is to distill the essence from its superficial trappings” [5]. This process is found everywhere, in philosophy, mathematics, natural language, art, and our own cognitive processes. In computer science, it is completely vital; without abstraction, we couldn’t possibly manage the sheer scale and intricacy of modern software.

The Modus Operandi of Abstraction

Based on the KRA (Knowledge Representation & Abstraction) model presented by Saitta and Zucker [2], abstraction operates through several key mechanisms:

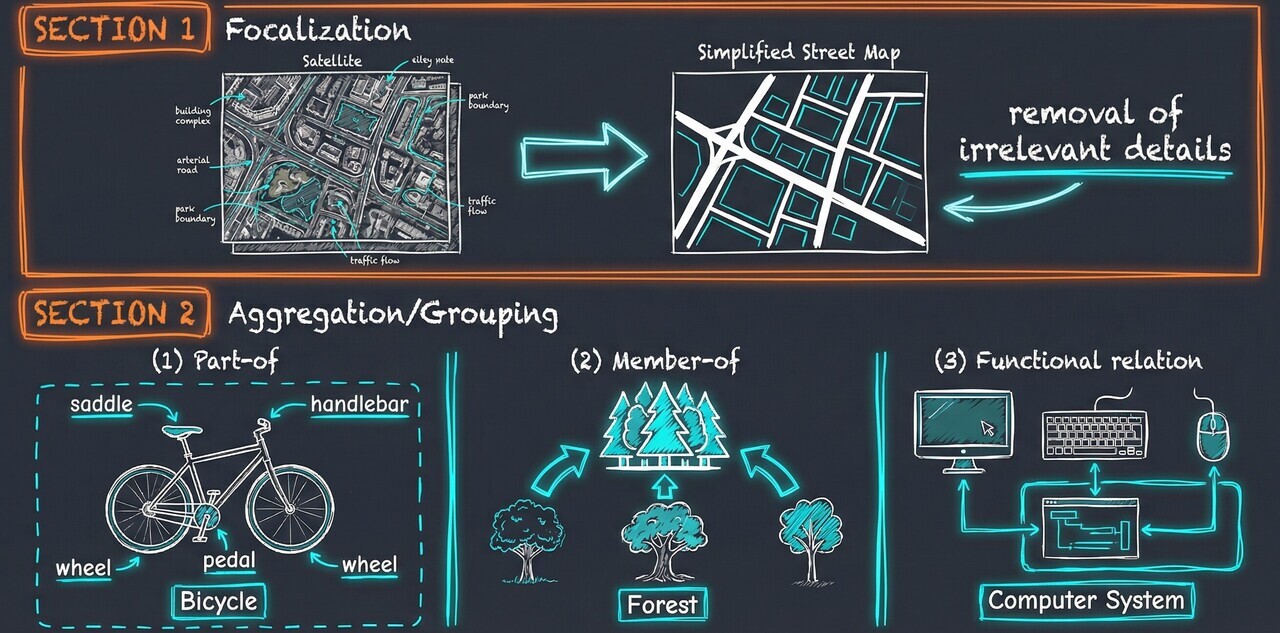

1. Focalization and Grouping

Figure. Focalization filters out irrelevant information to focus on what’s important, while grouping aggregates related elements into coherent structures through part-of, member-of, or functional relations.

Focalization refers to filtering out irrelevant information to focus only on what’s important. A satellite map abstracted to a simplified street map removes excess detail and leaves behind what’s contextually meaningful. Grouping aggregates related elements into coherent structures. A bicycle becomes an abstraction of wheels, pedals, and handlebars; a forest becomes a collection of individual trees.

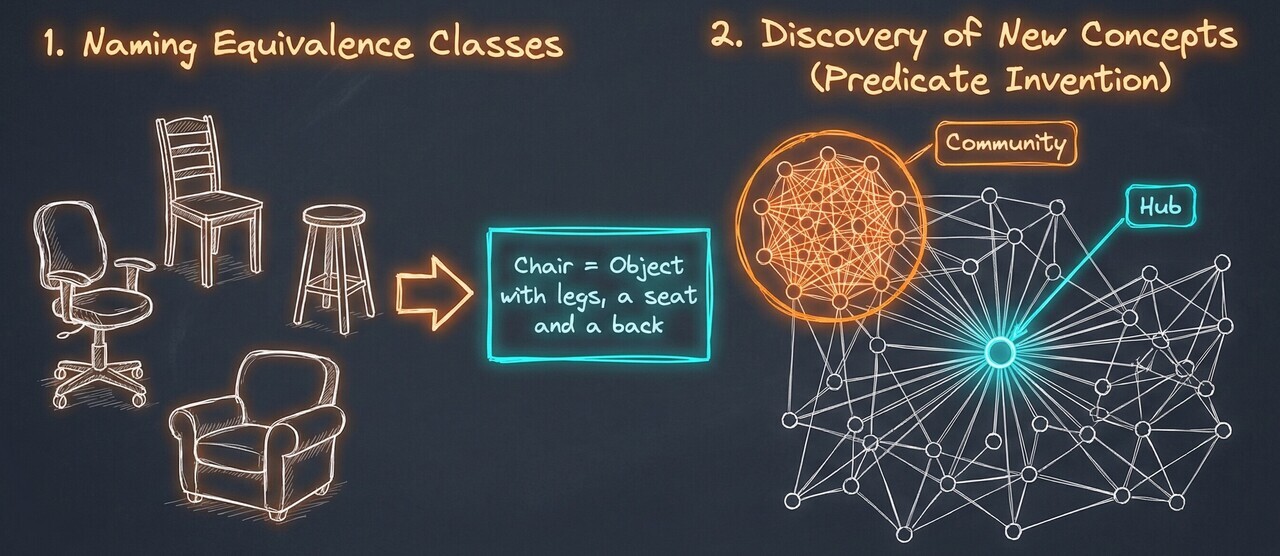

2. Equivalence and Concept Formation

Figure. Abstraction groups diverse instances into named concepts based on shared features, and discovers new higher-level concepts by recognizing patterns or structures.

Abstraction groups diverse instances into a single named concept based on shared features. All varied objects with legs, a seat, and a back become abstracted under the concept “Chair.” More powerfully, abstraction can create new higher-level concepts by discovering patterns. In a network, densely connected nodes may be abstracted as a “community” while highly connected central nodes form a “hub.”

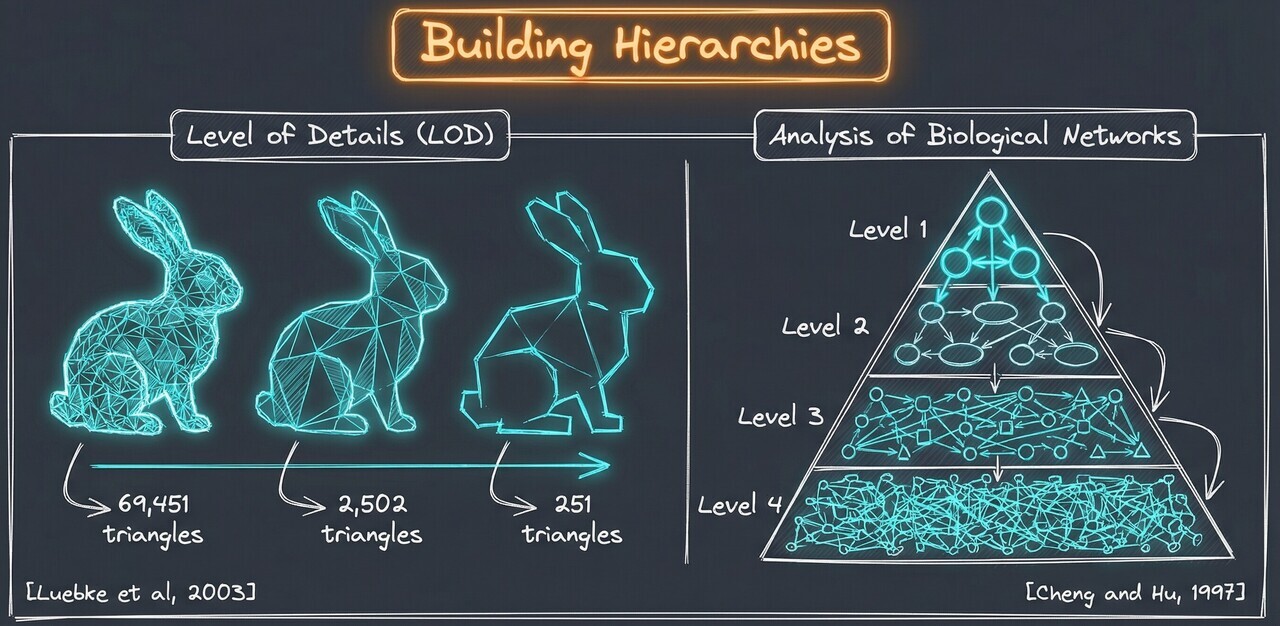

3. Building Hierarchies

Figure. Hierarchical structuring creates multiple levels of detail, enabling reasoning at different granularities. This is similar to a Level of Detail (LOD) model showing an object rendered at different resolutions.

Abstraction creates multiple levels of detail, enabling reasoning at different granularities. The “Level of Detail” (LOD) concept in graphics illustrates this perfectly. The same rabbit can be rendered with different triangle counts, each level a valid abstraction depending on the viewer’s needs.

Two Poles of Abstraction

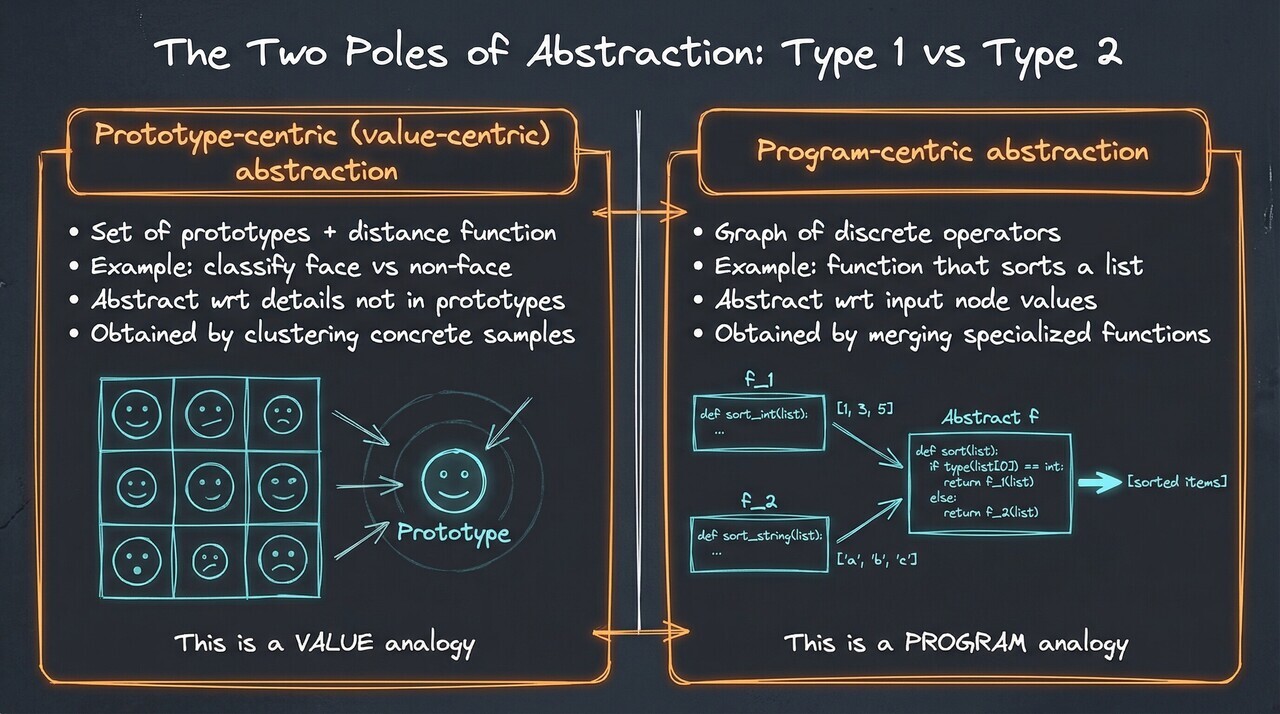

François Chollet’s work on the ARC-AGI benchmark [3] reveals a profound distinction in how abstraction operates:

Figure. Type 1 (Prototype-centric) abstraction represents concepts through typical examples and similarity measures, while Type 2 (Program-centric) abstraction generalizes over operations and behaviors as reusable computational patterns.

Type 1: Prototype-centric abstraction focuses on representing a concept through a set of prototypes, such as typical or average examples, and using a distance function to measure similarity [3]. This is what deep learning excels at: clustering concrete examples around shared values or characteristics.

Type 2: Program-centric abstraction concerns generalizing over operations or behaviors, not values [3]. A sorting function operates regardless of what list it receives because it abstracts over the specific content. This is achieved by merging multiple specialized functions into a single, reusable pattern.

Understanding both poles is essential for advancing AI systems capable of learning, generalizing, and reasoning across domains [3][6].

The Knowledge Level: Abstraction in AI Systems

The importance of abstraction in AI has deep theoretical roots. In his seminal 1982 work, Allen Newell introduced the concept of the Knowledge Level, a distinct level of system description that lies above the symbol level (code, data structures, algorithms) [7]. This framework provides a compelling theoretical foundation for understanding why approaches like AoT work.

The Knowledge Level Hypothesis

Newell proposed that intelligent systems can be understood at multiple levels, each with its own medium and laws of behavior:

| Level | Medium | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Device Level | Electrons, physical phenomena | Hardware physics |

| Circuit Level | Voltage, current | Electronic components |

| Logic/Bit Level | Bits, bit vectors | Binary operations |

| Symbol Level | Symbols, expressions | Programs, data structures |

| Knowledge Level | Knowledge | Goals, beliefs, rationality |

The crucial insight is that the Knowledge Level is characterized by knowledge as the medium and the principle of rationality as the law of behavior:

“If the agent has knowledge that one of its actions will lead to one of its goals, then the agent will select that action.”

At this level, we don’t need to understand how a system internally processes information. We predict its behavior by understanding what it knows and what it wants to achieve. This is precisely the kind of abstract reasoning that AoT aims to elicit in language models.

World-Oriented vs. System-Oriented

Newell distinguished between two orientations:

- Symbol Level (System-oriented): Focuses on internal workings such as data structures, algorithms, and computational steps

- Knowledge Level (World-oriented): Focuses on what the agent knows about the world and its goals

This distinction maps remarkably well to AoT’s structure:

| AoT Layer | Orientation | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Abstract levels ($A^1$) | World-oriented | Problem type, domain principles, strategic goals |

| Concrete levels ($A^k$) | System-oriented | Specific operations, calculations, implementations |

When AoT asks a model to first identify “This is a quadratic equation” before solving it, it’s essentially asking the model to operate at the Knowledge Level, reasoning about the type of problem and the general principles that apply, before descending to the Symbol Level for concrete computation.

Why This Matters for AI Reasoning

The Knowledge Level framework reveals why Chain-of-Thought can fall short. CoT operates primarily at the Symbol Level, generating a sequence of computational steps. It’s system-oriented, focused on how to execute operations. What’s missing is the Knowledge Level perspective: the abstract understanding of what kind of problem this is and what general knowledge applies.

AoT explicitly bridges these levels. By requiring each step to contain both abstract (why) and concrete (how) components, it forces models to maintain dual perspectives:

- Knowledge Level: What do I know about this class of problems? What’s my goal?

- Symbol Level: What specific operations will I perform? What computations are needed?

This dual-level reasoning mirrors how human experts approach problems. A mathematician doesn’t just manipulate symbols. They understand the meaning of the problem, recognize its type, recall relevant theorems, and then perform calculations. The Knowledge Level provides the strategic direction; the Symbol Level provides the tactical execution.

Knowledge Level Learning and LLMs

Newell also distinguished types of learning relevant to understanding how LLMs improve:

- Symbol Level Learning: Improvements only visible at the implementation level (e.g., caching, optimization)

- Deductive Knowledge Level Learning: Accumulating facts and rules that expand what the system “knows”

- Non-Deductive Knowledge Level Learning: Inductive learning that creates genuinely new knowledge

Current LLMs primarily operate through a form of compiled knowledge, specifically massive pattern matching at the Symbol Level with Knowledge Level behavior emerging implicitly [7][8]. The AoT approach may help make Knowledge Level reasoning more explicit and systematic, potentially improving the reliability and interpretability of AI reasoning [1].

This connection between Newell’s classic framework and modern prompting techniques reveals a deeper truth: the challenges we face in AI reasoning today are not entirely new. The distinction between knowing what to do and knowing how to do it has been central to AI since its inception. What AoT offers is a practical method to operationalize this distinction within the transformer architecture.

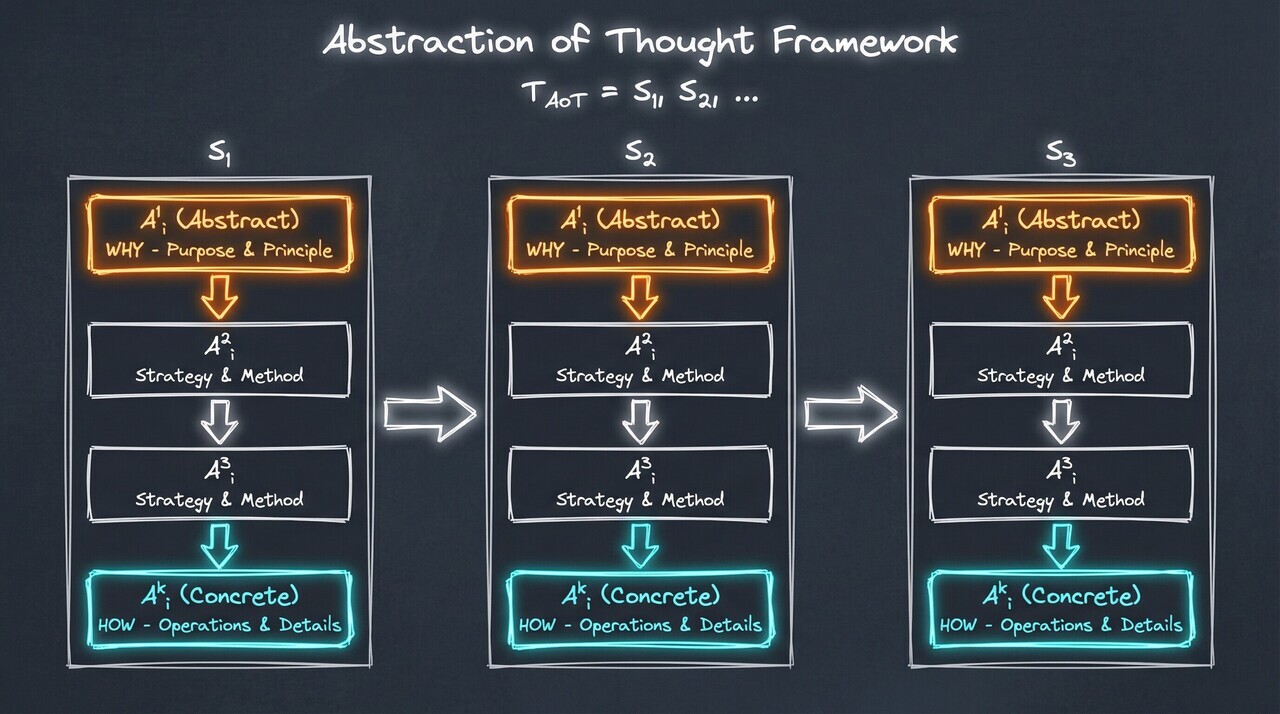

Abstraction of Thought: The Framework

Abstraction-of-Thought (AoT) formalizes multi-level thinking. Researchers represent a reasoning process as a sequence of steps ($T_{AoT} = S_1, S_2, \ldots$). Crucially, each step ($S_i$) isn’t monolithic; it contains an internal hierarchy of abstraction levels ($A^1_i, A^2_i, \ldots, A^k_i$):

- $A^1_i$: Represents the highest level of abstraction for that step, including its core purpose or the general principle being applied.

- $A^k_i$: Represents the most concrete level, including the specific operations, details, or data manipulations.

- Intermediate levels ($A^2_i$ to $A^{k-1}_i$): Bridge the gap between the high-level goal and the low-level execution.

Each step encapsulates a mini-plan, moving from why (the abstract goal) to how (the concrete actions). This explicit structure distinguishes AoT fundamentally from CoT.

Figure. Abstraction-of-Thought manifests as numbered steps, each beginning with a clear statement of its abstract purpose before elaborating on the details. The layering, meaning the visible hierarchy from abstract plan to concrete execution, is key.

AoT in Practice

This structured approach translates effectively to different domains:

Natural Language: AoT manifests as numbered steps, each beginning with a clear statement of its abstract purpose (e.g., “Step 1: Identify the core user need from the request”) before elaborating on the details. The final answer is often explicitly marked for clarity.

Code Generation: AoT encourages modularity. Functions or classes represent abstracted components, with comments explaining their purpose (the abstraction). The main execution block then calls these components, acting as the high-level plan orchestrating the concrete implementations.

In both cases, the layering, meaning the visible hierarchy from abstract plan to concrete execution, is key.

Teaching Abstraction: Empirical Results

To enable models to reason in this structured way, researchers developed the “AoT Collection,” a specialized dataset containing approximately 348,000 examples formatted according to AoT principles [1]. This dataset was generated using powerful LLMs in an automated pipeline, a fascinating instance of AI teaching AI to reason more effectively.

A key feature of the AoT Collection is its “hybrid” nature, incorporating reasoning examples expressed in both natural language and programming languages (like Python). This allows the model to learn flexibility, choosing the most appropriate modality for the task at hand.

When models fine-tuned on this AoT data were tested against challenging benchmarks like BigBench Hard (BBH), designed to push the boundaries of logical, mathematical, and linguistic reasoning, the results were striking [1]:

| Finding | Details |

|---|---|

| Significant Performance Gains | Models fine-tuned with AoT significantly outperformed counterparts using standard CoT. Llama 3 8B trained with AoT showed nearly 10% absolute improvement on BBH. |

| Strength in Algorithmic Tasks | Improvements were particularly pronounced on tasks requiring structured, step-by-step logical procedures such as mathematical reasoning and coding problems. |

| Structure is Key | Models trained on the original AoT format performed better than those trained on AoT content rewritten into linear CoT format, isolating the benefit of hierarchical structure. |

| Data Efficiency | Training with ~10,000 AoT examples yielded better performance than training on 300,000+ CoT examples. Learning the structure of abstract reasoning is more data-efficient. |

Perhaps most compellingly, the research indicated that learning the structure of abstract reasoning is significantly more data-efficient than simply processing more linear examples [1], a clear win for quality over quantity.

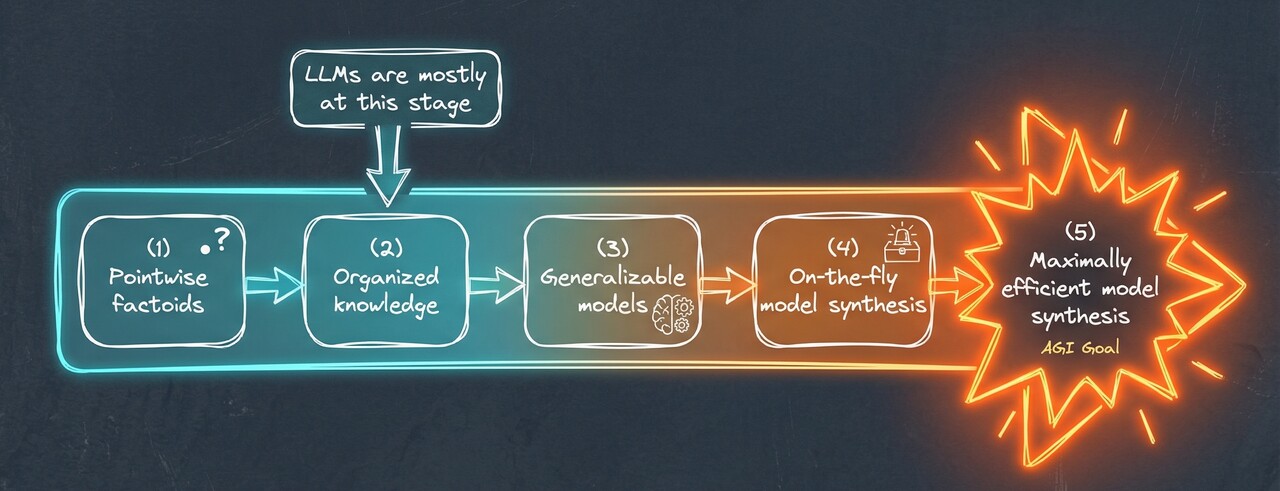

Where LLMs Fall on the AGI Trajectory

Understanding where current AI systems stand helps us appreciate why abstraction matters so much. Chollet’s framework [3] provides a conceptual trajectory toward Artificial General Intelligence:

Figure. A conceptual trajectory toward AGI, showing different stages of cognitive capability. LLMs currently operate primarily at the “Organized Knowledge” stage, capable of synthesizing and producing coherent answers but not yet building truly generalizable models or synthesizing solutions on-the-fly.

- Pointwise Factoids: The lowest level, recalling isolated facts without meaningful structure.

- Organized Knowledge ← LLMs are mostly here: Models organize and contextualize knowledge, producing coherent answers by synthesizing from large corpora. But they primarily recombine existing information rather than building new models.

- Generalizable Models: Systems create abstract, transferable models reusable across different tasks and contexts.

- On-the-Fly Model Synthesis: Intelligence constructs models dynamically in response to novel problems, including real-time planning, abstraction, and reasoning.

- Maximally Efficient Model Synthesis (AGI Goal): Rapidly synthesizing the best possible models for any problem encountered.

The path to AGI requires advancing beyond organized knowledge, enabling machines to autonomously create and refine internal models in a task-specific, abstract, and efficient way. This is precisely what abstraction-centric approaches like AoT aim to address.

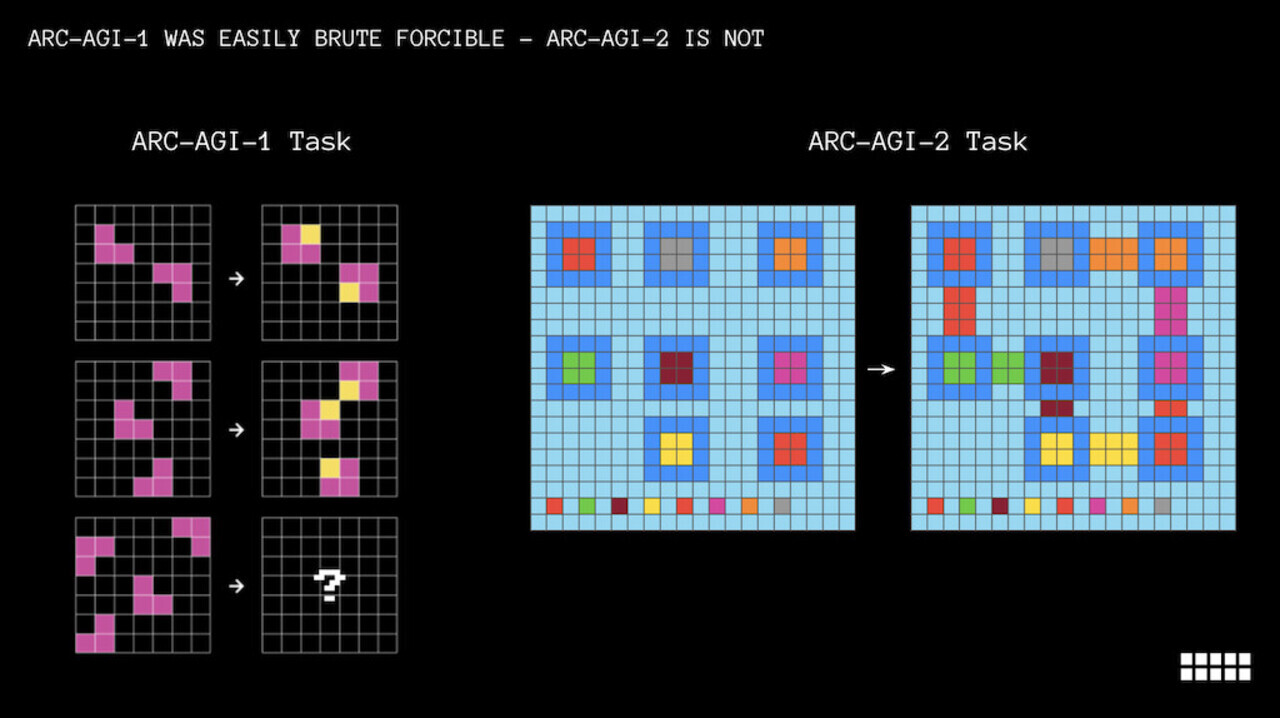

The ARC-AGI Challenge: Abstraction as the Benchmark

The Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus (ARC) [3][4] provides concrete evidence that abstraction is the key frontier:

Figure. ARC-AGI-1 (2019) challenged deep learning with tasks requiring novel abstraction. ARC-AGI-2 (2025) pushes further, specifically testing test-time reasoning and on-the-fly model synthesis.

- ARC-AGI-1 (2019) [3]: Challenged deep learning with visual reasoning tasks requiring novel abstraction from limited examples.

- ARC-AGI-2 (2025) [4]: Specifically tests test-time reasoning, which is the ability to construct new mental models during problem-solving, not just apply learned patterns.

As Chollet argues, “Solely measuring skill at any given task falls short of measuring intelligence, because skill is heavily modulated by prior knowledge and experience” [3]. True intelligence is skill-acquisition efficiency, meaning how quickly a system can generalize from minimal examples. Abstraction is the mechanism that enables this generalization.

Merging Deep Learning and Program Synthesis

The future likely lies in hybrid architectures that combine the best of both paradigms [2][3]:

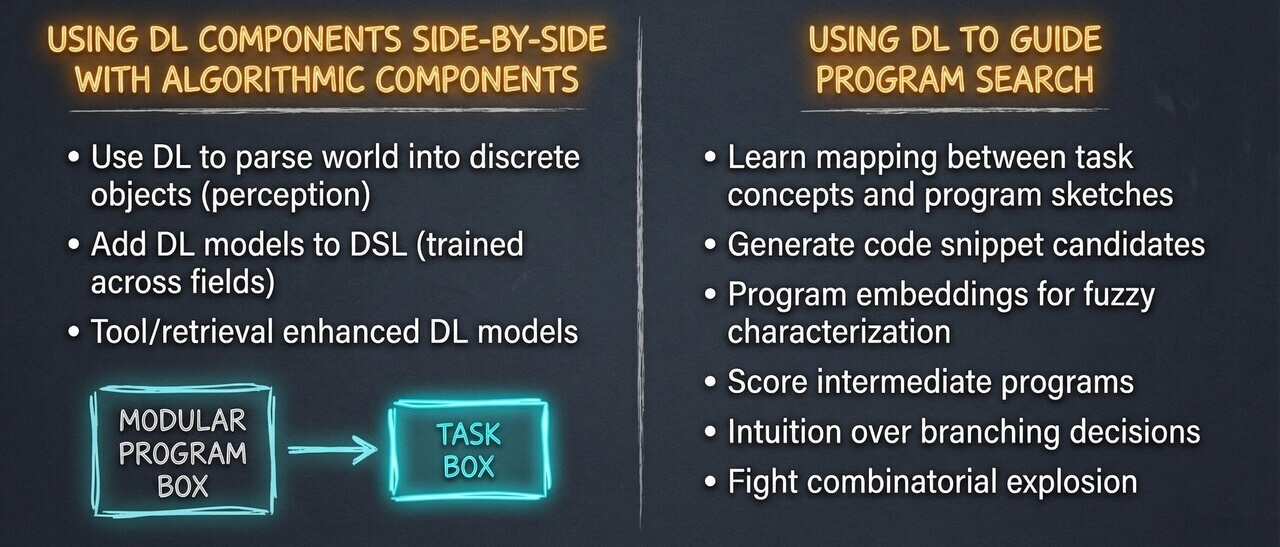

Figure. Hybrid architectures where deep learning handles perception and fuzzy matching while program synthesis provides structure and logic. This merger combines DL’s ability to learn from data with program synthesis’s ability to reason symbolically.

Side-by-side Integration:

- Deep Learning parses raw input into symbolic representations

- DL models can be embedded into Domain-Specific Languages (DSLs) as functional components

- Systems use retrieval-augmented or tool-enhanced models

DL Guiding Program Synthesis:

- DL learns to map from high-level task concepts to program “sketches”

- It helps generate code snippet candidates and program embeddings

- DL provides heuristic intuition over branching decisions, combating combinatorial explosion

This hybrid approach, where DL handles perception and generalization while program synthesis provides structure and precision, may be the path forward for building more flexible, intelligent, and general-purpose AI systems [3][6].

Practical Implications

The findings from AoT research have immediate practical implications:

For Prompt Engineering

When constructing prompts, explicitly encourage abstraction:

- Ask the model to identify the type of problem before solving

- Request a high-level strategy before implementation details

- Structure prompts to elicit multiple levels of reasoning

For Model Training

The data efficiency finding is crucial [1]:

- Quality of reasoning structure matters more than quantity of examples

- Training data should explicitly demonstrate abstract-to-concrete reasoning flows

- Hybrid formats (natural language + code) provide flexibility

For System Design

When building AI systems for complex reasoning:

- Incorporate explicit abstraction layers in the reasoning pipeline

- Allow the system to operate at multiple levels of detail

- Provide mechanisms for the system to “step back” and reconsider at higher abstraction levels

Connection to Spatial Reasoning

This work resonates with a 30-year thread connecting spatial reasoning to AI frontiers. My thesis work focused on spatial cognitive processes, specifically how humans represent and manipulate spatial knowledge mentally. The KRA model’s concepts of focalization, grouping, and hierarchies [2] are fundamentally spatial operations: zooming in/out, chunking regions, and navigating levels of detail.

AoT represents a convergence of these ideas with modern language models. The ability to reason at multiple levels of abstraction is essentially the cognitive equivalent of having multiple “zoom levels” on a problem, seeing both the forest and the trees, and knowing when to switch between views.

The ARC-AGI benchmark [3][4] explicitly tests this spatial-abstract reasoning capability. Tasks require recognizing patterns, applying transformations, and generalizing from minimal examples, all operations that demand both Type 1 (pattern recognition) and Type 2 (program synthesis) abstraction working in concert [3].

Concluding Remarks

Abstraction of Thought represents a significant conceptual shift in pursuing advanced AI reasoning. By moving beyond purely sequential processing and embracing structured, multi-level abstraction within the reasoning process itself, AoT demonstrates compelling empirical benefits: improved performance on complex tasks, enhanced data efficiency, and a potential framework for more robust handling of context.

More profoundly, AoT forces us to consider the very nature of thinking. The ability to conceptualize, to generalize, to plan at a high level before diving into specifics, is fundamental to human intelligence. Teaching our AI systems to explicitly manage abstraction may not just be a technique for better benchmark scores; it could be a critical step towards creating AI that reasons more deeply, understands more reliably, and collaborates with us more effectively on the complex challenges ahead.

The journey towards truly intelligent machines may depend on our ability to teach them not just what to think, but how to structure their thought, from the abstract heights down to the concrete ground.

References

[1] Ruixin Hong, Hongming Zhang, Xiaoman Pan, Dong Yu, Changshui Zhang. Abstraction-of-Thought Makes Language Models Better Reasoners. arXiv:2406.12442 [cs.CL], June 2024.

- Introduces the AoT framework and demonstrates significant improvements over Chain-of-Thought reasoning on BigBench Hard benchmarks.

[2] Lorenza Saitta and Jean-Daniel Zucker. Abstraction In Artificial Intelligence And Complex Systems. Springer, May 2013.

- Presents the KRA (Knowledge Representation & Abstraction) model, providing a unified framework for understanding abstraction operators in AI.

[3] François Chollet. On the Measure of Intelligence. arXiv:1911.01547 [cs.AI], November 2019.

- Articulates a formal definition of intelligence based on skill-acquisition efficiency and introduces the ARC benchmark for measuring human-like general fluid intelligence.

[4] ARC Prize Foundation. ARC-AGI-2. GitHub Repository, 2025.

- The second iteration of the Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus, specifically testing test-time reasoning capabilities.

[5] Robert Goldstone and Lawrence Barsalou. Reuniting Perception and Conception. Cognition 65 (1998) 231-262.

- Illustrates ways in which conceptual processing is grounded in perception, relevant to understanding abstraction’s cognitive foundations.

[6] Ruocheng Wang, Eric Zelikman, Gabriel Poesia, Yewen Pu, Nick Haber, Noah D. Goodman. Hypothesis Search: Inductive Reasoning with Language Models. arXiv:2309.05660 [cs.LG], May 2024.

- Proposes generating hypotheses at multiple levels of abstraction to improve inductive reasoning on ARC and similar benchmarks.

[7] Allen Newell. The Knowledge Level. Artificial Intelligence 18(1):87-127, 1982.

- Introduces the Knowledge Level as a distinct computer systems level characterized by knowledge as the medium and the principle of rationality as the law of behavior.

[8] B. Chandrasekaran. Understanding Control at the Knowledge Level. AAAI Technical Report FS-94-03, 1994.

- Applies Knowledge Level analysis to control systems, demonstrating how differences in knowledge availability determine solution architectures.