artwork by Gemini 3 Pro (Nano Banana Pro)

You Only Look Once: 8 Years of Food Detection Evolution

FoodInsight

Part 1 of 3Eight years ago, we trained a YOLO v2 model to detect 100 types of Japanese food in real-time. It required compiling C code, writing custom Python scripts, and carefully tuning configuration files. Today, the same task takes three commands and an afternoon. This is the story of how food detection, and deep learning tooling more broadly, has evolved from 2018 to 2026.

In 2018, we wrote about YOLO for Real-Time Food Detection [6], documenting our journey to build a “Food Watcher” using Joseph Redmon’s Darknet framework [1] and the UEC FOOD 100 dataset [2]. The result was impressive for its time: 70 fps food detection on a GTX TitanX, recognizing everything from sushi to hamburgers.

“The obsession of recognizing snacks and foods has been a fun theme for experimenting with the latest machine learning techniques.”

That obsession hasn’t faded. But the landscape has transformed dramatically. What once required a dedicated NVIDIA GPU, manual C compilation, and hours of configuration now runs on a MacBook with Apple Silicon, installs via pip, and trains while you sleep.

This post revisits food detection through the lens of YOLO11 [3] and the FoodInsight project [4], showing what’s changed, what’s stayed the same, and why 2026 is the best time ever to train your own object detection models.

Figure. YOLO11 food detection pipeline: Input images from the UEC FOOD 100 dataset [2] flow through convolutional layers and a detection head, outputting bounding boxes with class labels and confidence scores for diverse Japanese dishes.

The Evolution of YOLO

Before diving into the technical details, it’s worth appreciating how far YOLO has come. The original “You Only Look Once” paper from 2015 [5] introduced a radical idea: instead of scanning an image thousands of times looking for objects, process the entire image in a single neural network pass.

Figure. The evolution of YOLO from 2015 to 2024: From Joseph Redmon’s revolutionary single-pass detection concept through Ultralytics’ democratization of object detection, to today’s efficiency-focused YOLO11. Orange highlights mark key breakthroughs (v1, v5, v11), while cyan accents indicate major architectural innovations.

The story arc is remarkable. Joseph Redmon’s original Darknet implementation was written in pure C, fast but requiring careful compilation and platform-specific tweaks [1]. After Redmon stepped away from computer vision research in 2020, the community forked and evolved the codebase. Ultralytics emerged as the de facto standard, wrapping everything in a clean Python API that just works [3].

From research code to production-ready library. From C compilation to pip install. From NVIDIA-only to Apple Silicon, Intel, and edge devices.

Then vs Now: The Setup Comparison

The most striking difference between 2018 and 2026 is not the model architecture. It is the developer experience.

2018: The Darknet Way

Here’s what training YOLO v2 required in 2018:

1. Download and compile Darknet (C code, Makefile tweaks for GPU)

2. Download pre-trained weights manually (darknet19_448.conv.23)

3. Write custom Python scripts for bounding box conversion

4. Create food100.names file (class names, one per line)

5. Create food100.data file (paths to train/test lists)

6. Create yolov2-food100.cfg (50+ lines, manual filter calculation)

7. Run training with precise command syntax

8. Edit config again for testing (batch=1, subdivisions=1)

The configuration file alone required calculating filter counts manually:

# number of filters calculated by (#-of-classes + 5)*5

# e.g. (100 + 5)*5 = 525

filters=525

classes=100

Get this wrong? Silent failures or garbage predictions.

2026: The Ultralytics Way

Here’s the modern equivalent:

# Install (once)

pip install ultralytics

# Convert dataset (once)

python convert_uec_to_yolo.py datasets/UECFOOD100 --output datasets/UECFOOD100_yolo

# Train

yolo detect train data=data.yaml model=yolo11s.pt epochs=150 device=mps

That’s it. The conversion script generates a data.yaml file automatically:

path: /path/to/UECFOOD100_yolo

train: images/train

val: images/val

test: images/test

nc: 100

names: ['rice', 'eels on rice', 'pilaf', ...]

No manual filter calculations. No separate train/test configs. No C compilation. The framework handles everything.

Pain Points Eliminated

| 2018 Pain Point | 2026 Solution |

|---|---|

| C compilation across platforms | Pure Python, pip install |

| Manual filter calculation | Automatic architecture |

| Separate train/test configs | Single model object |

| No built-in visualization | Integrated plots, metrics |

| NVIDIA GPU required | Apple Silicon, CPU, Intel |

| Manual weight downloads | Auto-download from hub |

Training on Apple Silicon

Perhaps the most surprising change: you no longer need an NVIDIA GPU.

In 2018, CUDA was the only path to reasonable training speeds. A GTX TitanX was a $1,200 investment, plus a workstation to house it. Today, Apple’s Metal Performance Shaders (MPS) backend enables GPU-accelerated training on any M-series Mac.

python datasets/train.py \

--data /path/to/UECFOOD100_yolo/data.yaml \

--model yolo11s.pt \

--epochs 150 \

--batch 32 \

--device mps \

--name food100_best

The --device mps flag is the only change needed. Everything else works identically.

Hardware Comparison

| Metric | 2018 (GTX TitanX) | 2026 (M4 Pro) |

|---|---|---|

| Memory | 12GB VRAM (dedicated) | 48GB unified |

| Power | 250W | 40W |

| Setup | CUDA, cuDNN, driver hell | Just works |

| Cost | ~$1200 GPU alone | Integrated |

| Noise | Jet engine | Silent |

| Form factor | Desktop tower | Laptop |

Training YOLO11s on UEC FOOD 100 [2] takes approximately 15-18 minutes per epoch on the M4 Pro. Our 80-epoch run completed in about 22 hours, with early stopping available when the model converges.

The Dataset: UEC FOOD 100 (Still the Standard)

Some things don’t change. The UEC FOOD 100 dataset from the University of Electro-Communications in Tokyo remains the gold standard for food detection research [2].

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Images | 14,361 |

| Classes | 100 Japanese food categories |

| Annotations | Bounding boxes per food item |

| License | Non-commercial research |

The dataset’s strength is its real-world nature: photos taken in actual dining settings, not studio shots. Multiple foods appear in single frames. Lighting varies. Presentations differ.

There’s now also UEC FOOD 256 [2] with 31,395 images across 256 classes, adding international foods. However, the original 100-class version trains faster and achieves higher per-class accuracy, so it remains the best starting point.

Dataset Conversion

The original UEC format stores bounding boxes in a bb_info.txt file per class directory:

img x1 y1 x2 y2

1 0 143 370 486

2 20 208 582 559

YOLO expects normalized center coordinates in per-image label files:

class_id x_center y_center width height

0 0.231250 0.524167 0.462500 0.571667

In 2018, we wrote three separate Python scripts to handle this conversion. Today, a single unified script handles everything, including automatic train/val/test splits:

python convert_uec_to_yolo.py datasets/UECFOOD100 \

--output datasets/UECFOOD100_yolo \

--train-ratio 0.8 \

--val-ratio 0.1 \

--test-ratio 0.1

Understanding the Training Output

One area where 2026 dramatically outshines 2018: metrics and observability.

What We Saw in 2018

Region Avg IOU: 0.767684, Class: 0.285230, Obj: 0.376508

9998: 5.413931, 5.206974 avg, 0.000010 rate, 2.222207 seconds

The guidance was simple: “Stop when average loss stops decreasing.” No precision/recall breakdown. No per-class analysis. Just watch a number go down and hope.

What We See in 2026

Every epoch produces comprehensive metrics:

epoch,mAP50,mAP50-95,precision,recall,box_loss,cls_loss,dfl_loss

48,0.780,0.596,0.737,0.704,0.833,1.383,1.344

49,0.782,0.594,0.725,0.721,0.833,1.381,1.342

50,0.787,0.598,0.762,0.697,0.820,1.359,1.335

Let us break down what these mean:

Figure. Visual explanation of object detection metrics: IoU measures bounding box overlap, Precision tracks false positives, Recall tracks missed detections, and mAP averages precision across IoU thresholds (lenient at 0.50, strict at 0.50-0.95).

mAP50-95 (Primary Metric): Mean Average Precision averaged across IoU thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95. This is the strictest measure, as high scores require both correct classification AND precise bounding boxes.

mAP50 (Lenient Metric): Precision at IoU=0.50. A detection counts as correct if there’s at least 50% overlap with ground truth. Always higher than mAP50-95.

Precision: Of all detections made, what fraction were correct? High precision means few false positives.

Recall: Of all actual foods in the images, what fraction did we detect? High recall means few missed foods.

IoU (Intersection over Union): Measures bounding box accuracy:

IoU = Area of Overlap / Area of Union

An IoU of 0.50 means the predicted box overlaps 50% with the ground truth. An IoU of 0.95 requires near-perfect alignment.

Current Training Results

Our YOLO11s model on UEC FOOD 100 [2] achieved the following metrics after 80 epochs of training:

| Metric | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| mAP50-95 | 0.60 | Good overall detection accuracy |

| mAP50 | 0.79 | Strong detection at IoU 0.50 |

| Precision | 0.75 | Few false positives |

| Recall | 0.71 | Finds most foods in images |

For a 100-class food detection problem with visually similar categories such as multiple noodle types and rice dishes, these numbers represent solid performance. The model was trained using transfer learning from COCO pretrained weights [9], which helped achieve good results even with the relatively small UEC FOOD 100 dataset.

The Classic Tests: Revisited

In the 2018 post, we highlighted several memorable test cases. Let’s revisit them with YOLO11.

Test 1: The Hot Dog Test

“Ever since the HBO show Silicon Valley released a real AI app that identifies ‘hot dogs, and not hot dogs’, recognizing hot dog is the golden test standard for any food detection.”

Figure. YOLO11 detecting hot dogs across various styles: classic with mustard (0.89), sesame bun pair (0.93), loaded with toppings (0.83), and ketchup drizzle (0.95). The Silicon Valley “not hot dog” test? Passed with flying colors.

Test 2: The Hamburger Challenge

From fast food classics to gourmet creations, hamburgers vary wildly in presentation. Can the model handle Big Macs, homemade burgers, and everything in between?

Figure. YOLO11 detecting hamburgers across the spectrum: classic patty (0.84), stacked Big Mac style (0.88), gourmet with fresh tomato (0.72), and McDonald’s meal with fries (0.56). Note the multi-class detection catching french fries (0.41) in the same frame.

Test 3: Soupy Things

Noodles in broth pose a unique challenge: the food is partially submerged and obscured.

Figure. YOLO11 detecting ramen noodle dishes with confidence scores from 0.51 to 0.95, successfully handling partially obscured food items in broth.

Test 4: Eggs in Many Forms

Eggs appear in countless preparations: fried, rolled, wrapped, or folded into omelets. Can the model distinguish between visually distinct egg dishes?

Figure. YOLO11 detecting diverse egg preparations: omurice-style omelet (0.81), Japanese tamagoyaki rolled omelet (0.77), crispy egg roll (0.85), and classic egg sunny-side up (0.56).

Test 5: Pizza in Every Style

From single slices to whole pies, takeout boxes to restaurant plates. Can the model recognize pizza across varied presentations and toppings?

Figure. YOLO11 detecting pizza across diverse styles: slice on paper plate (0.88), margherita in delivery box (0.87), mushroom pizza (0.62), and shrimp pizza (0.80).

Deployment: Beyond the Desktop

In 2018, deployment meant running Darknet [1] on a machine with an NVIDIA GPU. Period.

./darknet detector demo data/food100.data cfg/yolov2-food100.cfg weights/final.weights

No GPU? No detection.

2026: Deploy Everywhere

YOLO11 exports to virtually any runtime [3]:

| Target | Format | Command |

|---|---|---|

| Raspberry Pi | NCNN [8] | yolo export model=best.pt format=ncnn |

| iOS | CoreML | yolo export model=best.pt format=coreml |

| Android | TFLite | yolo export model=best.pt format=tflite |

| Web | ONNX.js | yolo export model=best.pt format=onnx |

| Intel CPUs | OpenVINO | yolo export model=best.pt format=openvino |

| Any platform | ONNX | yolo export model=best.pt format=onnx |

The FoodInsight project targets Raspberry Pi deployment, enabling a $50 computer to run food detection at the edge [4]:

# Export for Raspberry Pi (NCNN format) [8]

yolo export model=runs/detect/food100_best/weights/best.pt format=ncnn

# Deploy the NCNN model folder to Pi

# Run inference on-device, no cloud required

Privacy-preserving, always-available food detection for about the cost of a restaurant meal.

Performance Comparison

Let’s put numbers to the progress:

| Metric | YOLO v2 (2018) [1] | YOLO11 (2026) [3] |

|---|---|---|

| Framework | Darknet (C) | Ultralytics (Python) |

| Base model size | ~200MB | 22MB (yolo11s) |

| Inference speed | ~70 fps (TitanX) | 120+ fps (M4 Pro) |

| mAP50 | ~0.65-0.70 (estimated) | 0.79 |

| Setup time | Hours | Minutes |

| Config lines | 50+ | <10 |

| Deployment targets | NVIDIA GPU only | Everything |

The model is smaller, faster, more accurate, and infinitely easier to use.

What’s Next: The FoodInsight Vision

Food detection is a means to an end. We are building FoodInsight, a platform that demonstrates two practical applications of YOLO11 food detection.

Snack Watching: FoodInsight

The first application is a smart snack inventory monitoring system for office break rooms. Picture a Raspberry Pi with a camera mounted above the snack shelf:

Figure. FoodInsight deployment concept: A Raspberry Pi with camera monitors the snack shelf, detecting items taken or added in real-time. Bounding boxes show detected items with counts, while warning indicators flag low stock.

The FoodInsight Architecture:

- Edge AI detection: YOLO11n runs directly on the Raspberry Pi using NCNN format [8], achieving 4-6 FPS with no cloud dependency

- Privacy-by-design: Only inventory counts are stored, never images. ROI masking ensures only the snack shelf is processed

- Real-time tracking: ByteTrack [7] maintains object persistence across frames, detecting when items are taken or restocked

- Consumer access: A lightweight PWA lets anyone check current snack availability from their phone

- Zero cloud cost: SQLite database runs locally, making the entire system self-contained

The complete solution costs under $140 in hardware (Raspberry Pi 5 + Camera Module 3) and demonstrates how edge AI transforms simple object detection into practical workplace automation. What once required expensive cloud infrastructure now runs entirely on a credit-card-sized computer.

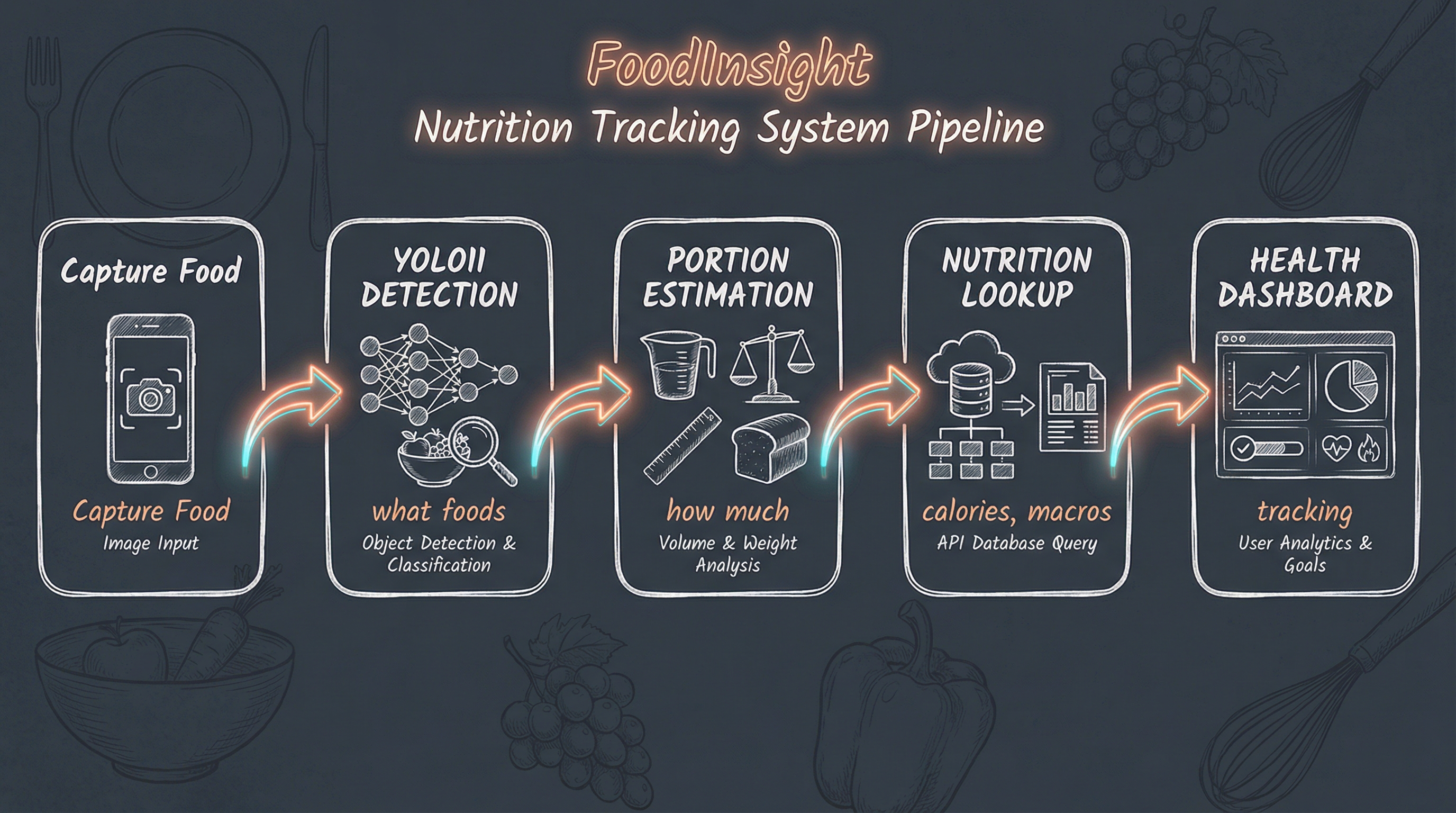

Nutrition Tracking Pipeline: FoodInsight

The second application extends food detection toward automated nutrition tracking: snap a photo of your meal, get calorie and macro estimates, log it to your health app.

Figure. The FoodInsight nutrition tracking pipeline: from camera capture through YOLO11 detection, portion estimation, nutrition lookup, to health dashboard visualization.

YOLO11 handles the first step beautifully. The remaining pieces:

- Portion estimation: Either through depth sensing, reference objects, or learned size estimation

- Nutrition database: Mapping detected classes to nutritional information

- User interface: Mobile app or kitchen-mounted display

The hardware exists. The models work. The snack watching application is complete, and the nutrition tracking pipeline is the next frontier.

Concluding Remarks

Eight years is a long time in deep learning. What required a dedicated GPU workstation, C compilation expertise, and careful manual configuration now runs on a laptop with three commands.

Key takeaways:

- Simplification: The Ultralytics ecosystem has made YOLO accessible to everyone

- Democratization: Apple Silicon and CPU-based training remove the NVIDIA barrier

- Better results: Modern architectures achieve higher accuracy with less effort

- New deployment targets: Edge devices, mobile, and web are now first-class citizens

- Same great data: UEC FOOD 100 remains the gold standard for food detection

The original 2018 post concluded:

“AI does enjoy the food watching!”

Eight years later, AI is better at it than ever, and now anyone can train their own food detector in an afternoon.

The obsession continues.

Appendix: Quick Start Guide

Want to train your own food detection model? Here’s the minimal path:

Prerequisites

- Python 3.10+

- macOS with Apple Silicon, or Linux with NVIDIA GPU

Steps

# 1. Install Ultralytics

pip install ultralytics

# 2. Download UEC FOOD 100

wget http://foodcam.mobi/dataset100.zip

unzip dataset100.zip

# 3. Convert to YOLO format (use FoodInsight conversion script)

git clone https://github.com/bennycheung/FoodInsight

python FoodInsight/datasets/convert_uec_to_yolo.py UECFOOD100 --output UECFOOD100_yolo

# 4. Train

yolo detect train \

data=UECFOOD100_yolo/data.yaml \

model=yolo11s.pt \

epochs=100 \

device=mps # or 'cuda' for NVIDIA, 'cpu' for CPU-only

# 5. Test

yolo detect predict \

model=runs/detect/train/weights/best.pt \

source=your_food_photo.jpg

That’s all. Welcome to 2026.

References

[1] Joseph Redmon. Darknet: Open Source Neural Networks in C. PJReddie.com, 2016.

- The original YOLO implementation framework written in C, providing the foundation for real-time object detection research.

[2] Matsuda, Y., Hoashi, H., and Yanai, K. Recognition of Multiple-Food Images by Detecting Candidate Regions. IEEE ICME, 2012.

- The UEC FOOD 100 dataset from the University of Electro-Communications, containing 14,361 images across 100 Japanese food categories.

[3] Ultralytics. YOLO11 Documentation. Ultralytics, 2024.

- The modern Python-based YOLO implementation providing state-of-the-art object detection with simple APIs and extensive deployment options.

[4] Benny Cheung. FoodInsight Project. GitHub, 2026.

- The FoodInsight project repository containing dataset conversion scripts, training pipelines, and deployment configurations for food detection.

[5] Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R., and Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. CVPR, 2016.

- The seminal paper introducing the YOLO approach to object detection, enabling real-time processing by treating detection as a single regression problem.

[6] Benny Cheung. YOLO for Real-Time Food Detection. Benny’s Mind Hack, 2018.

- The original blog post documenting food detection using YOLO v2 and Darknet, serving as the baseline for this 8-year retrospective.

[7] Zhang, Y., Sun, P., Jiang, Y., et al. ByteTrack: Multi-Object Tracking by Associating Every Detection Box. ECCV, 2022.

- High-performance multi-object tracking algorithm that associates detection boxes across frames, enabling persistent object identification in video streams.

[8] Tencent. NCNN: High-Performance Neural Network Inference Framework. GitHub, 2017.

- Optimized neural network inference framework for mobile and embedded platforms, enabling efficient CPU-based inference on ARM devices like Raspberry Pi.

[9] Lin, T.Y., Maire, M., Belongie, S., et al. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. ECCV, 2014.

- Large-scale object detection dataset used for pre-training YOLO models, providing transfer learning benefits for domain-specific applications like food detection.