artwork by Gemini 3 Pro

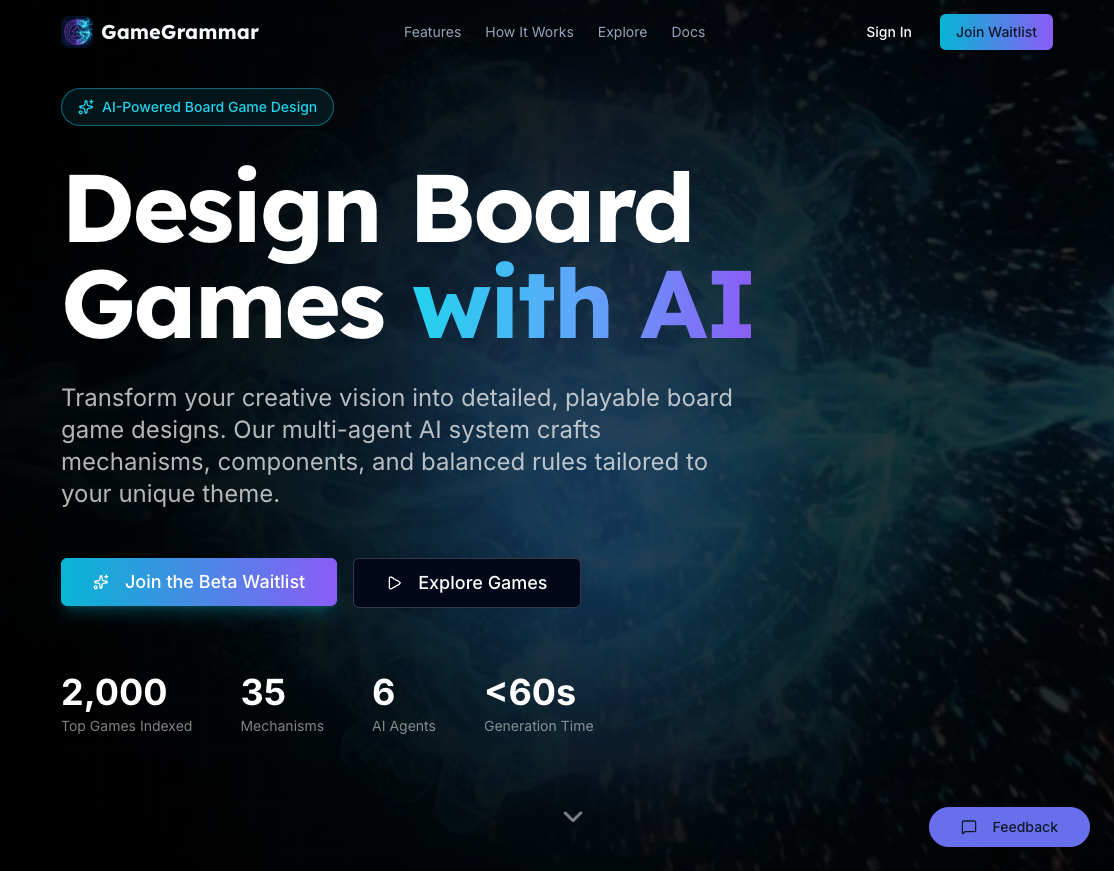

Introducing GameGrammar: AI-Powered Board Game Design

Game Architecture

Part 5 of 7I typed twelve words into a text box and got back a complete board game. Mechanics, components, scoring tables, a hex map, a four-phase turn structure, and a critic that told me the game was broken. The whole thing took 73 seconds. This is what happens when you give a structured game taxonomy to six AI agents and let them argue about your design.

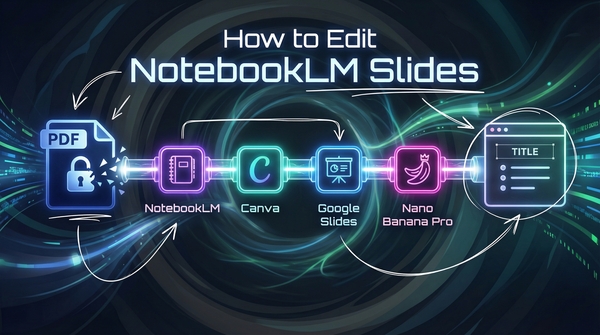

Figure. GameGrammar transforms a theme and constraints into a complete board game design through six specialized AI agents.

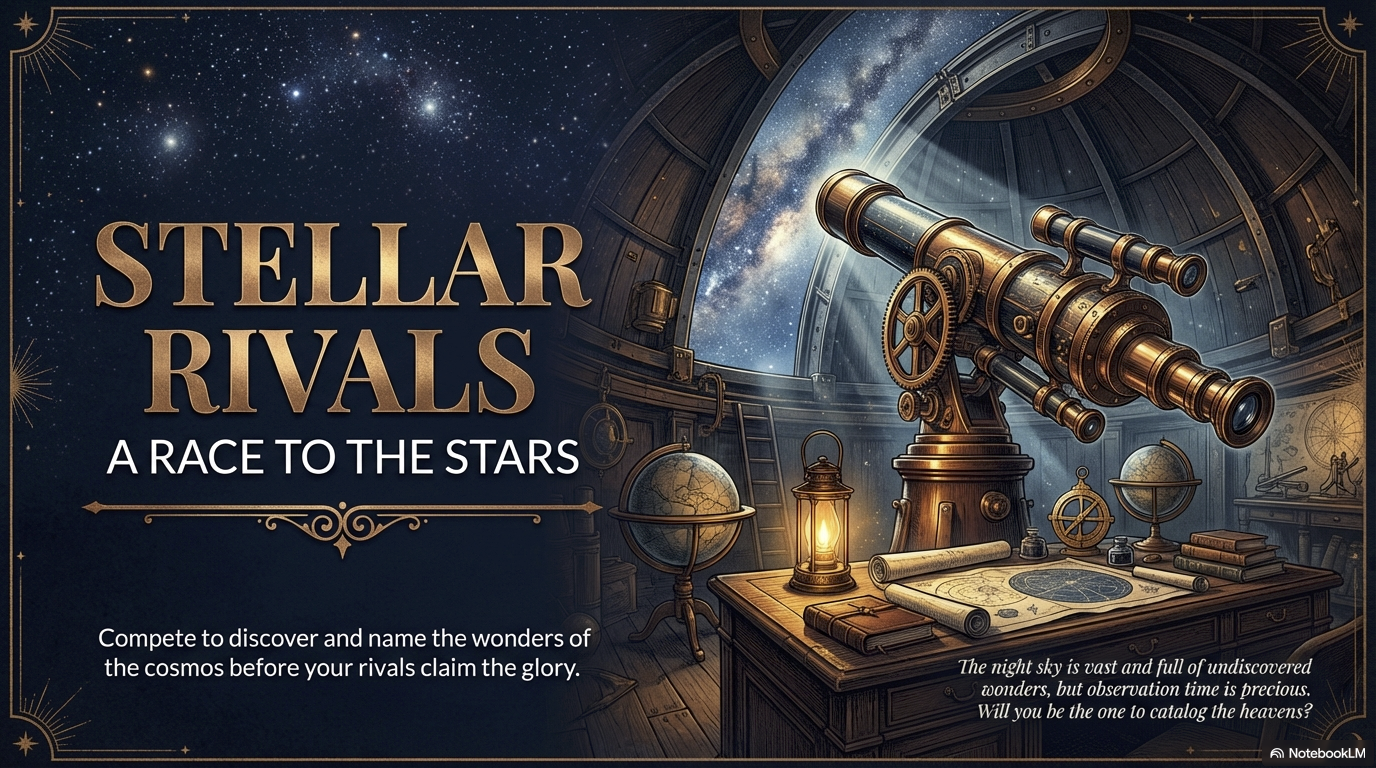

The twelve words were: “Rival astronomers racing to name celestial objects before their competitors claim the glory.”

What came back was Stellar Rivals: A Race to the Stars, a 2-4 player competitive game about 19th-century astronomers exploring a hex grid of stellar sectors, collecting celestial objects, and racing to complete constellations. It had specific action point costs, a scoring table with five distinct paths to victory, equipment upgrade cards, and a balance critique that flagged two high-severity issues I would have needed weeks of playtesting to discover.

I did not design this game. I did not prompt-engineer it into existence through twenty rounds of back-and-forth with ChatGPT. I typed a theme, set some constraints, and hit Generate.

This article is the story of how that works, why it is different from asking an LLM to “design a board game,” and what it means for the future of game design. This is also Part 5 of the Game Architecture series, where we have been building toward this moment since we first mapped the structure of tabletop games in Part 4 [1]. If you want to understand the design theory behind how GameGrammar works, including its philosophical foundations and the co-design relationship between human designers and AI, see Part 6: The Theory of Generative Board Game Design.

The Playtesting Graveyard

Before we look at what GameGrammar produces, we need to understand the problem it solves. Because the problem is not “I want AI to design games for me.” The problem is the blank page.

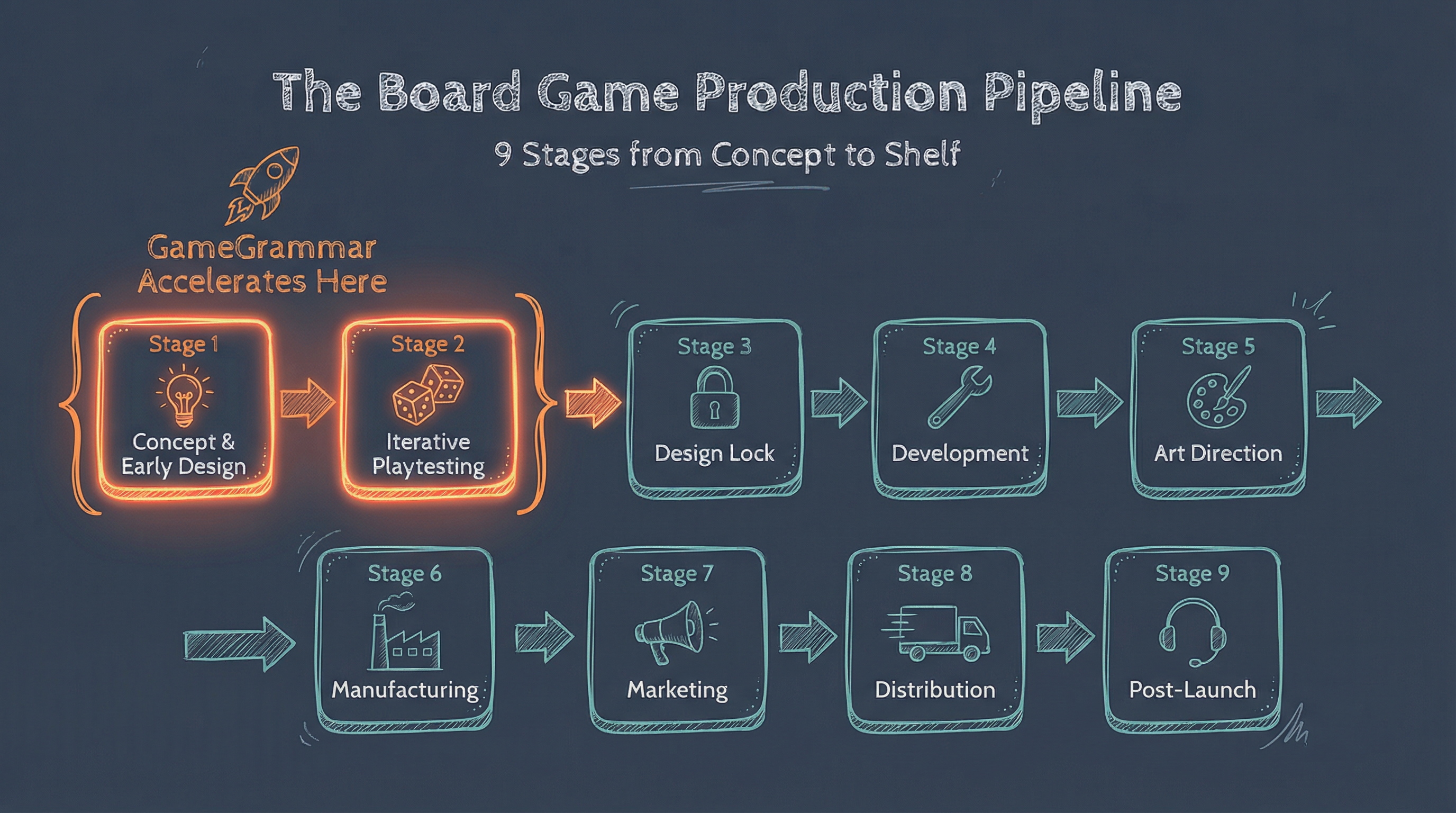

Creating a published board game is a nine-stage journey [2], and most people only see the last few stages: the box on the shelf, the Kickstarter campaign, the review video. What they do not see is Stages 1 and 2, where designers actually spend most of their time.

| Stage | Phase | What Happens |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Concept & Early Design | Core idea, initial mechanics, paper prototype |

| 2 | Iterative Playtesting | Cut, merge, rewrite rules; stress-test systems |

| 3-9 | Design Lock through Post-Launch | Development, art, manufacturing, marketing, distribution, support |

Six more stages stand between a playtested prototype and a box on a shelf: publisher development, art direction, manufacturing, marketing, distribution, and post-launch support. But the graveyard is in Stages 1 and 2.

“Most ‘cool mechanics’ die here, and should.” [2]

The playtesting graveyard is well-populated. A designer spends months developing a resource-trading mechanic, runs a blind playtest, and discovers it creates a dominant strategy. The mechanic gets cut. The designer starts over. This cycle is essential, but it is also where motivation erodes, especially for solo designers without a team to sustain momentum.

The blank page is the first enemy. Before a designer can even begin the playtesting gauntlet, they need a concept worth testing. Not just a theme, but a coherent combination of mechanics, components, player dynamics, and victory conditions that might, with sufficient iteration, become a real game.

Figure. The nine-stage board game production pipeline. GameGrammar accelerates Stages 1 and 2, where designers spend the most time and where promising ideas most often die.

I built GameGrammar at Dynamind Research [5], an AI consulting and product studio that bridges theoretical AI research with practical enterprise implementation, to attack this specific problem. Not to replace game designers, not to automate the creative process, but to eliminate blank-page paralysis and give designers structured starting points worth iterating on. It operates at Stages 1 and 2, where the designer’s challenge is generating enough viable concepts to find the gem worth polishing.

Stellar Rivals: Watching Six Agents Build a Game

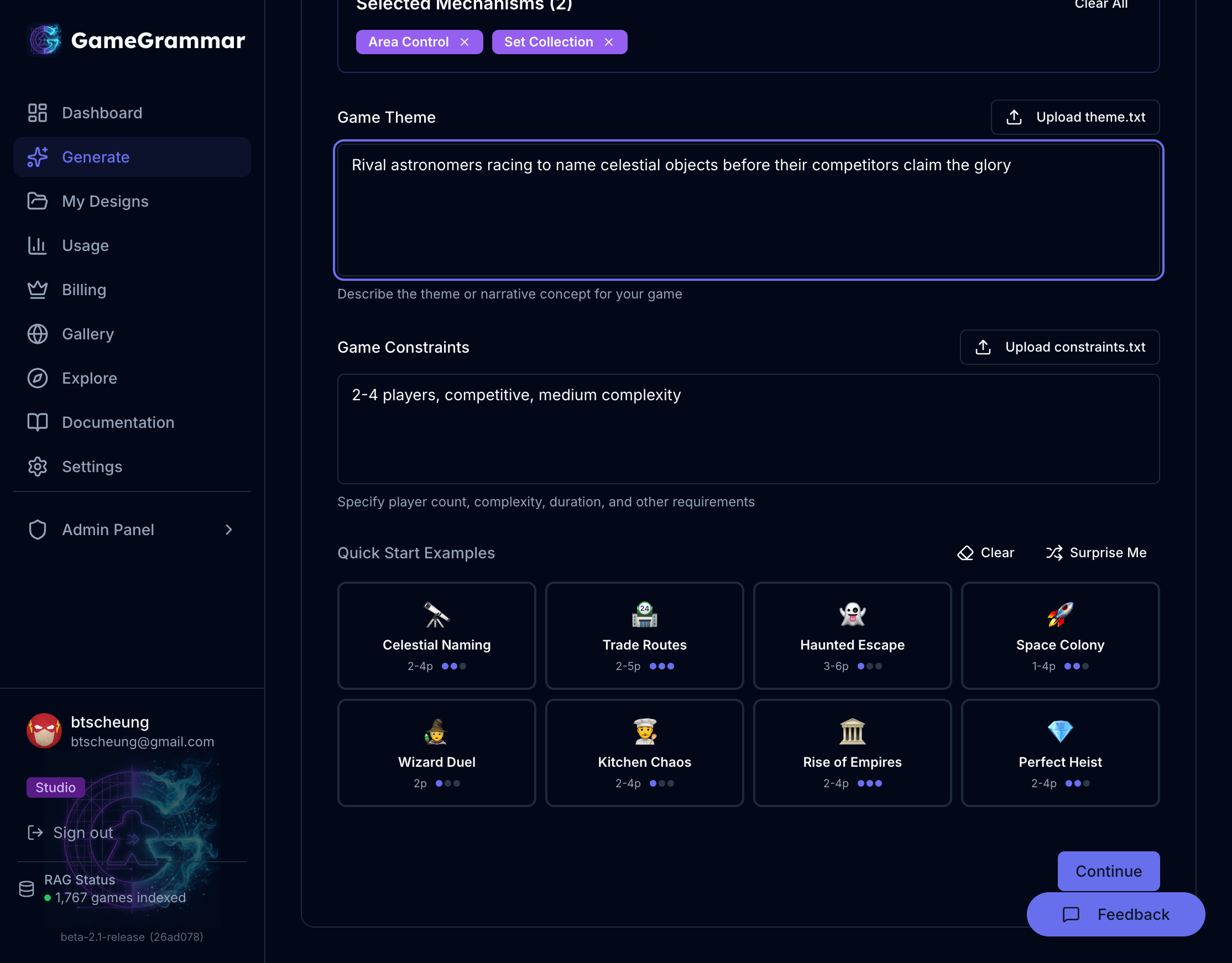

Here is what it actually looks like. You open GameGrammar, type a theme, and set some constraints:

Figure. The input: a theme, constraints, and optionally pre-selected mechanisms. Or just type a sentence and let the system choose.

The theme can be anything: “Medieval merchants trading spices along the Silk Road,” “Deep sea explorers discovering lost civilizations,” or in our case, “Rival astronomers racing to name celestial objects” with constraints “2-4 players, competitive, medium complexity, 45-60 minutes.”

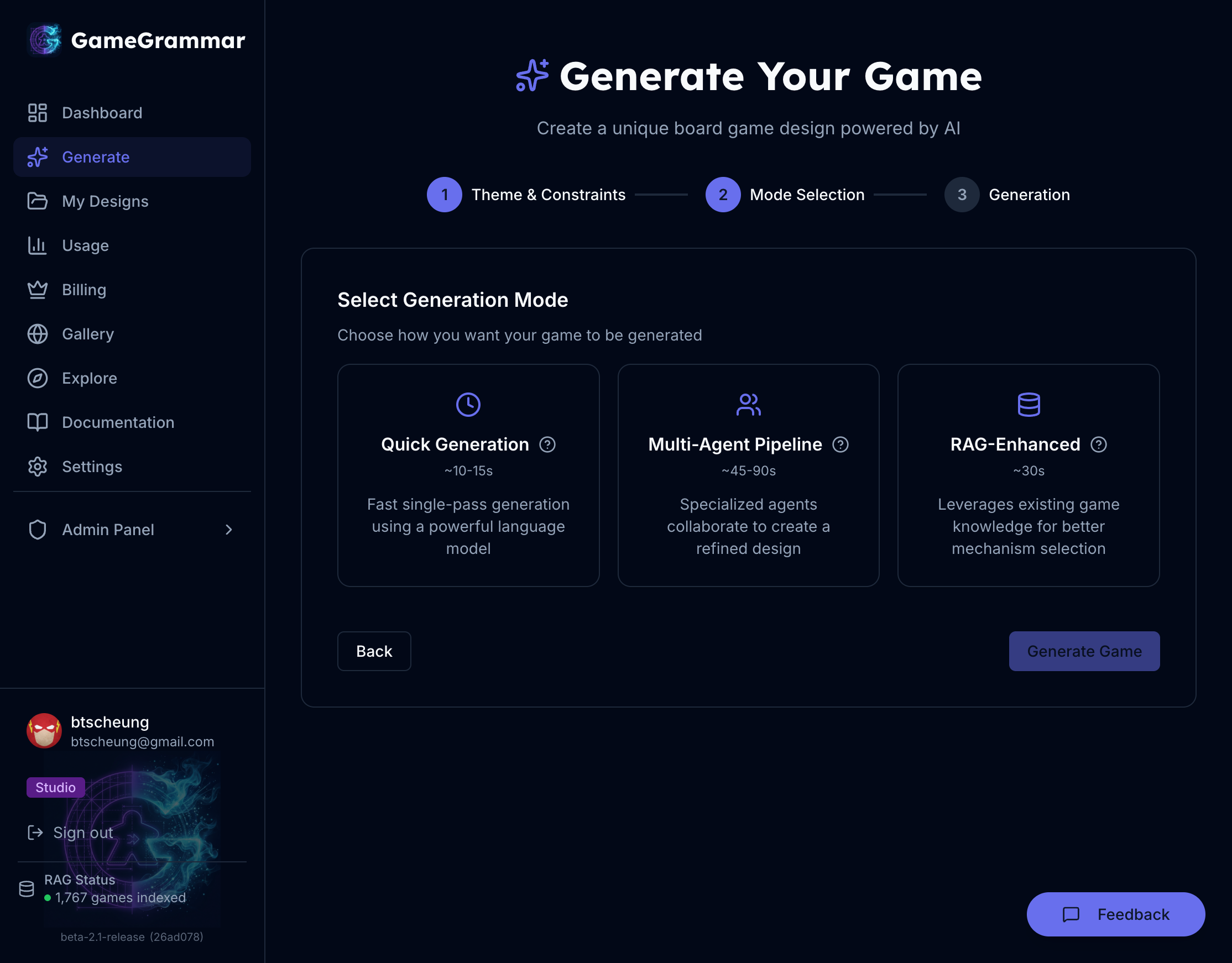

Then you choose a generation mode. I picked Multi-Agent because it reveals what makes GameGrammar fundamentally different from a single-prompt approach: six specialized AI agents working in sequence, each reading the complete output of every agent before it.

| Mode | Speed | What Happens |

|---|---|---|

| Quick | ~15 seconds | A single powerful model generates the complete design in one pass |

| Multi-Agent | 45-90 seconds | Six specialized AI agents collaborate sequentially, each building on the last |

| RAG-Enhanced | ~30 seconds | Generation grounded in data from 2,000+ published BoardGameGeek games [4] |

Figure. Choose a generation mode: Quick for rapid prototyping, Multi-Agent for the full six-agent pipeline, RAG-Enhanced for designs grounded in real published games.

Seventy-three seconds later:

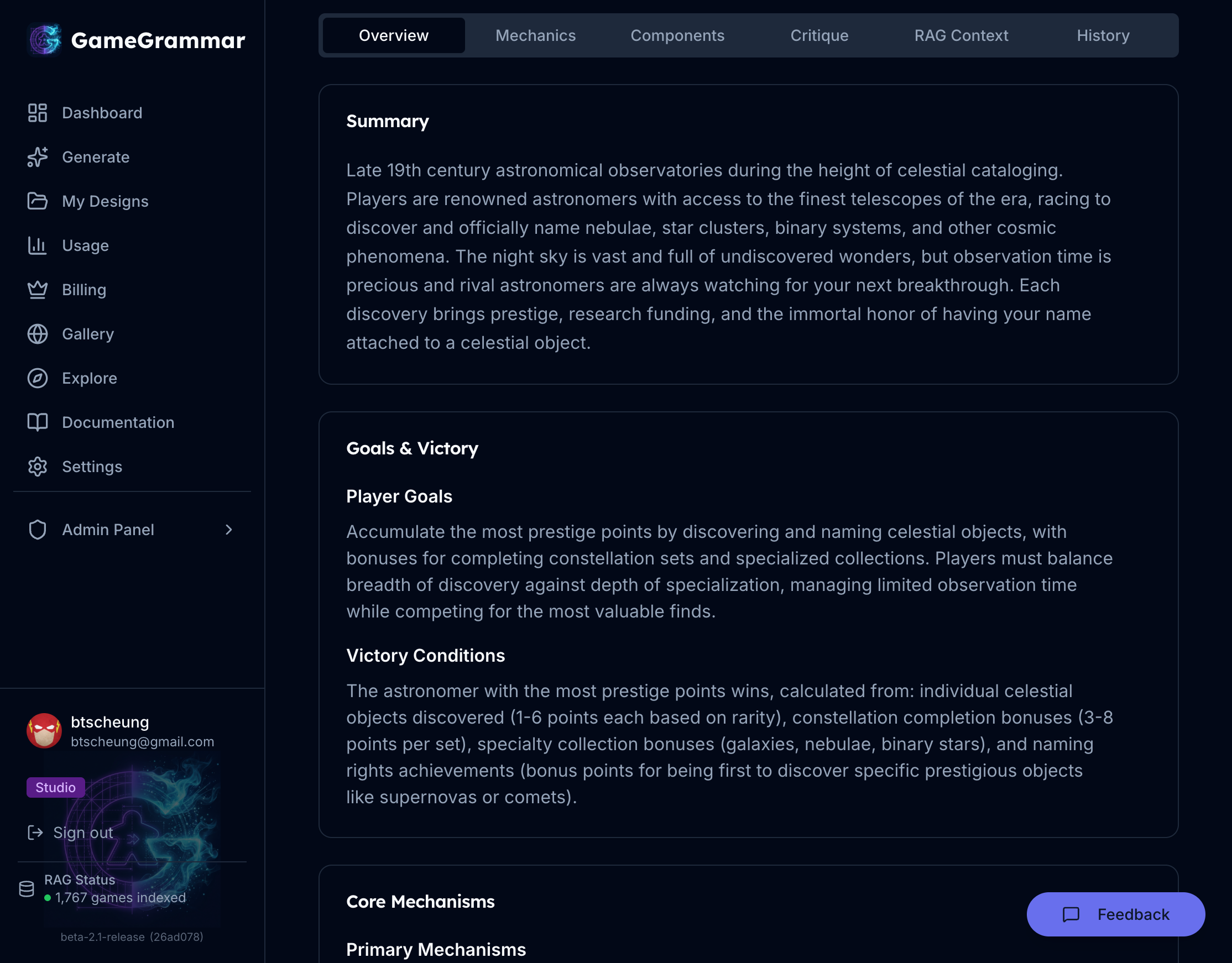

Figure. Stellar Rivals: A Race to the Stars. A complete game design from twelve words and four constraints.

Figure. An Overview of the Expedition: 2-4 players, 45-60 minutes, medium complexity. Every discovery attaches your name to a celestial object.

What comes back is not a paragraph of suggestions. It is a structured design document with concrete component counts, specific point values, defined turn phases, and identified balance concerns. The kind of document you can hand to a playtester and say, “Let’s try this.”

Here is what each agent did, and why the sequence matters.

The MechanicsArchitect Picks the Bones

The first agent does not think about themes or components. It thinks about mechanisms. It has access to a curated taxonomy of 35 game mechanisms organized into seven categories [1][3], and its job is to select a compatible set.

Figure. Six specialized agents working in sequence. Each agent sees and builds on the complete output of all previous agents.

For Stellar Rivals, it chose four:

- Action Points (6 per turn) for the core decision economy

- Set Collection for constellation-based scoring

- Hidden Information via face-down celestial object tiles

- Area Movement across a hex grid of stellar sectors

Why these four? Because the MechanicsArchitect checks a compatibility matrix built from co-occurrence patterns in real published games. Action Points and Set Collection appear together frequently because scarcity-based economies pair well with collection goals. Hidden Information and Area Movement create spatial discovery, which is exactly what “rival astronomers” implies. The agent is not guessing. It is pattern-matching against thousands of published designs.

Figure. The Mechanism Browser: 35 mechanisms in seven categories (Turn Order, Action Selection, Resource/Economy, Conflict/Territory, Cards/Deck, Information, Other), with compatibility data drawn from real published games.

This taxonomy is not arbitrary. It is derived from the analysis of thousands of published tabletop games and established game design literature [1][3]. The MechanicsArchitect selects from this curated vocabulary, not from the fuzzy patterns in an LLM’s training data.

The ThemeWeaver Dresses the Skeleton

Agent two reads the mechanism selections and translates them into a 19th-century astronomical discovery setting:

- Six stellar sectors (Inner Planets, Asteroid Belt, Outer Planets, Nebula Field, Deep Space, Galactic Core)

- Celestial objects including quasars, galaxies, binary stars, and nebulae

- Weather conditions that modify observation costs

- Research tokens representing scientific progress

This is where “Area Movement” becomes “moving your telescope between stellar sectors” and “Hidden Information” becomes “face-down celestial object tiles you reveal by observing.” The mechanisms have not changed. They have been given a skin.

Figure. Mapping the Celestial Sphere: six hex sectors with movement costs in Action Points. Distance equals cost.

The ComponentDesigner Makes It Physical

Agent three specifies every physical piece:

- 6 hex sector tiles

- 48 face-down celestial object tiles (8 per sector)

- Equipment upgrade cards

- Research tokens and observation point markers

- Player telescope markers

This matters because a game that exists as a concept is not the same as a game that can be prototyped. Specific counts, specific card types, specific token functions. A designer can read this list and start cutting cardboard.

The DetailsArchitect Writes the Rules

Agent four defines the turn structure as a four-phase loop:

| Phase | Activity | Key Decision |

|---|---|---|

| Telescope Positioning | Simultaneously choose a sector | Where to observe this turn |

| Observation | Spend 6 action points on movement, revealing, and claiming | Resource allocation under scarcity |

| Analysis | Score claimed objects, check constellation completion | Set collection progress |

| Equipment | Spend research tokens on upgrades | Engine building investments |

Figure. The Astronomer’s Routine: a four-phase loop of Positioning, Observation, Analysis, and Equipment.

Here is where the design starts to feel like a real game. Consider Dr. Sarah Chen’s turn:

She spends 3 of her 6 observation points to move her telescope to the Galactic Core sector. She uses a Spectrographic Filter equipment card to reveal a tile for a reduced cost of 1 point, uncovering a Quasar. She spends her final 2 points to reveal an Elliptical Galaxy. The Quasar is worth more raw points, but the Galaxy completes her Andromeda constellation, netting her 4 points for the object plus an 8-point constellation bonus. She earns research tokens and later acquires the Observatory Network card.

That is a real decision with real trade-offs. Points now versus points later. Individual value versus set completion. Spend on movement or spend on discovery. These are the kinds of tensions that make games interesting, and they emerged from twelve words of input.

The scoring system has five distinct paths:

| Scoring Category | Mechanism | Points |

|---|---|---|

| Celestial Objects | Per-object claim | 1-6 based on rarity |

| Constellation Bonuses | Set completion | 3 / 5 / 8 (escalating) |

| Binary Systems | Pair discovery | 2x printed value |

| Naming Rights | First discovery bonus | 3-4 points |

| Galaxy Clusters | End-game collection | +2 per galaxy (if 4+) |

Figure. Five strategic paths to victory: object rarity, constellation sets, binary pairs, naming rights, and galaxy clusters.

“Your Game Is Broken”

This is the part that surprised me when I first built it.

Agents five and six are not designers. They are critics. The BalanceCritic evaluates the complete design for fairness and strategic depth. The FunFactorJudge assesses whether the game would actually be fun to play. And they do not pull punches.

Here is what the BalanceCritic said about Stellar Rivals:

| Issue | Severity | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Observatory Network card circumvents movement economy | High | Limit uses per game or increase cost to 2-3 extra points |

| Constellation difficulty gap, easy sets too rewarding | High | Adjust bonus structure (e.g., 3-6-10) to reflect difficulty |

| Sector overcrowding with 4 players | Medium | Scale tiles per sector with player count |

| Starting 6 observation points feels restrictive | Medium | Increase to 7-8 or allow 1-2 point carryover |

| Research token conversion rate (2:1) is inefficient | Medium | Improve to 3:2 for tactical viability |

Two high-severity issues. The Observatory Network card, which Dr. Sarah Chen acquired in our play example, actually breaks the movement economy that makes the rest of the game work. And the constellation bonus structure rewards easy sets disproportionately, creating a dominant strategy.

The FunFactorJudge rated the design 7/10, identifying the “thrill of discovery” from hidden tiles and the tight action-point economy as primary tension sources.

Figure. The BalanceCritic identifies strengths alongside critical issues with specific fix recommendations. This is not flattery. It is a design review.

Think about what just happened. The system generated a game, then told me it was broken, then told me exactly how to fix it. That kind of feedback normally requires weeks of playtesting, multiple playtest groups, and a designer honest enough to see their own blind spots. Here, it happened in the same 73-second generation pass.

GameGrammar does not just generate. It argues with itself about the quality of its own output.

“Can’t I Just Use ChatGPT?”

Fair question. You can absolutely ask ChatGPT to design a board game. It will produce fluent, confident text. It will tell you about a game with “resource management” and “strategic depth” and “high replayability.”

But try handing that output to a playtester. Ask them: how many action points do I get per turn? What happens when two players land on the same tile? How many cards are in the starting deck? The answer, almost always, is that the LLM generated the appearance of a game design without the substance.

| Aspect | Raw LLM | GameGrammar |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Single prompt, single pass | 6 specialized agents in sequence |

| Mechanisms | Drawn from fuzzy training data | 35-mechanism curated taxonomy |

| Game References | May hallucinate titles and stats | 2,000+ real BGG games indexed |

| Output Structure | Unstructured prose | Consistent schema with components, rules, scoring |

| Self-Critique | None unless explicitly prompted | Built-in BalanceCritic and FunFactorJudge |

| Iteration | Copy-paste-re-prompt | Workbench with targeted expand, re-evaluate, consistency |

| Balance Analysis | Generic advice | Severity-rated issues with specific fix recommendations |

The difference is not marginal. A raw LLM might tell you a game has “resource management.” GameGrammar will tell you that each player receives 6 observation points per turn, movement costs 1-3 points based on sector distance, revealing a tile costs 2 points, and research tokens convert to observation points at a 2:1 ratio. One is a suggestion. The other is a specification.

Figure. Suggestions versus specifications. GameGrammar produces designs with concrete numbers, specific components, and self-critical evaluation.

What Happens After You Hit Generate

Generation is the beginning, not the end. No game design is right on the first pass, not even one that comes with a built-in critic. GameGrammar provides a workbench for iterating on generated designs:

Expand any section to add detail. Re-evaluate to run the BalanceCritic and FunFactorJudge again after you have made changes. Consistency Check verifies that components match rules, that referenced items actually exist, that quantities add up. You can generate variants, create cover art, and export to JSON, Markdown, or PDF.

The Design Library stores every design with search, filters, and version history. A Community Gallery lets designers share their work and browse what others have created, finding mechanism combinations they might not have considered.

Figure. The design workbench. Expand, re-evaluate, check consistency, generate variants, create cover art, export. Generation is the start of the process, not the end.

This mirrors the real design workflow: prototype, test, iterate. GameGrammar compresses the generation side of that loop so designers can spend their time where it matters most, at the table with real players.

What Remains Human

I want to be clear about what GameGrammar cannot do, because the boundaries matter more than the capabilities.

It cannot playtest the game. No AI can simulate the experience of four people around a table discovering that a mechanic is tedious or that a scoring path is dominant. It cannot read the room, the laughter, the frustration, the surprise on a player’s face when a combo clicks. It cannot navigate the publication journey, the manufacturing economics, the publisher relationships, the convention pitching. And it cannot make taste judgments. Is a 45-minute game about Victorian astronomers interesting? That is a question for the designer and their audience, not for an algorithm.

GameGrammar is a design accelerator, not a replacement [2]. It frees designers from blank-page paralysis and gives them structured starting points worth iterating on. Everything that happens after, the playtesting, the polishing, the publishing, remains the designer’s craft.

Try It

GameGrammar is available today in public beta at gamegrammar.dynamindresearch.com.

The free tier includes 5 daily generations. Quick mode produces a complete design in about 15 seconds. The Multi-Agent pipeline takes under 90 seconds and delivers a design with built-in balance critique and fun-factor assessment.

To generate your first game:

- Create an account at gamegrammar.dynamindresearch.com

- Enter a theme: anything from “pirates racing for treasure” to “quantum physicists competing for Nobel Prizes”

- Set your constraints: player count, complexity, duration

- Choose Multi-Agent mode for your first design

- Read the balance critique. That is the part that will surprise you.

The Explore section offers a Mechanism Browser with all 35 mechanisms, a compatibility matrix showing which mechanisms pair well together, and a Game Explorer for browsing 2,000+ published games as inspiration.

Concluding Remarks

This is Part 5 of the Game Architecture series. In Part 4, we built a structured vocabulary for understanding tabletop games [1]. Now, that vocabulary has become a creative engine with a name, an interface, and a generate button.

Twelve words. Seventy-three seconds. A complete game with five scoring paths, a hex grid, equipment upgrades, constellation bonuses, and a critic that tells you where it breaks.

The blank page is no longer your enemy. It is your launchpad.

This article showed you the what. If you want to understand the why, Part 6: The Theory of Generative Board Game Design explores the design theory behind GameGrammar. It covers the three-layer architecture that separates mechanics from theme, the co-design relationship between human designers and AI agents, and the philosophical question of whether AI can understand fun. If you are curious about what makes this approach different at a deeper level, that is where to go next.

Series

- Unlocking the Secrets of Tabletop Games Ontology (Part 4)

- » Introducing GameGrammar: AI-Powered Board Game Design (Part 5)

- GameGrammar: The Theory of Generative Board Game Design (Part 6)

References

[1] Benny Cheung. Unlocking the Secrets of Tabletop Games Ontology. bennycheung.github.io, Feb 2025.

- Part 4 of the Game Architecture series, the ontology foundation for this work

[2] Board Game Design Pipeline Analysis. Dynamind Research, Jan 2026.

- Nine-stage pipeline from concept to post-launch, positioning GameGrammar at Stages 1-2

[3] Geoffrey Engelstein, Isaac Shalev. Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design: An Encyclopedia of Mechanisms. CRC Press, 2022.

- Comprehensive reference for game mechanism taxonomy and classification

[4] BoardGameGeek. The largest board game database and community.

- Source for the 2,000+ game index used in RAG-enhanced generation

[5] Dynamind Research. AI consulting and product development studio.

- Creator of GameGrammar, bridging theoretical AI research with practical product implementation

[6] Benny Cheung. Generative Ontology: When Structured Knowledge Learns to Create. arXiv:2602.05636, Feb 2026.

- The formal research paper behind GameGrammar’s design theory and generative architecture