artwork by Stable Diffusion AI

Spatial Reasoning in AGI - Insights from Philosophical Perspectives

Spatial Reasoning

Part 3 of 4Philosophy of AI

Part 6 of 6Spatial understanding is indeed an important aspect of achieving Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), which refers to machines possessing human-level intelligence across a wide range of tasks and domains. Despite the belief that advanced Large Language Models (LLMs), such as GPT-4, demonstrate some AGI capabilities, these models may encounter difficulties when explaining concepts requiring spatial reasoning skills.

LLMs excel at processing and generating text on a vast scale; however, they can struggle to convey ideas that involve understanding and manipulating visual and spatial relationships between objects in a three-dimensional space. This limitation arises because spatial reasoning skills are not easily communicated through language alone.

[2024/10/04] We can listen to this article as a Podcast Discussion, which is generated by Google’s Experimental NotebookLM. The AI hosts are both funny and insightful.

images/spatial-reasoning-in-agi/Podcast_Spatial_Reasoning_AGI.mp3

Figure. An illustration inspired by the artistic styles of M.C. Escher, Salvador Dalí, and Wassily Kandinsky that represents the concept of AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) requiring spatial reasoning and cognitive abilities. (image credit: Stable Diffusion).

In this article, we express our dissatisfaction with existing AI systems’ limitations in AGI and propose a broader perspective that incorporates philosophical ideas. By examining the works of philosophers who have studied human cognition and spatial reasoning, we aim to explore new research directions that may bring us closer to the AGI goal. We argue that understanding the underlying principles of human intelligence and incorporating these insights into AI systems could lead to models with improved versatility, adaptability, and spatial reasoning capabilities, ultimately advancing the pursuit of AGI.

Why Spatial Reasoning?

Spatial reasoning is a subfield of artificial intelligence that enables a computer to comprehend its surroundings based on its position. This involves identifying objects within the environment and then skillfully manipulating them in a practical manner. Applications of spatial reasoning include navigation, object manipulation, and environmental interpretation. It’s currently employed in areas such as GIS, robotics and gaming.

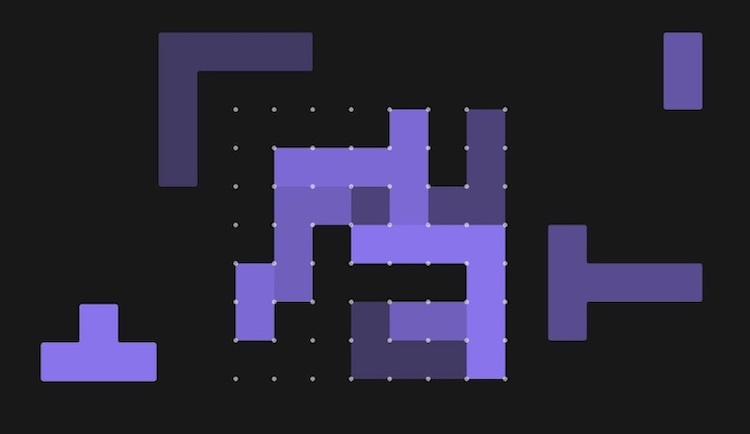

To understand personally, imaging a simple puzzle (in the illustration) that requires spatial reasoning skills might be easily solvable by us. We are able to answer the questions of (1) is there a solution to fit all the loose pieces in the space? and (2) how can we pack all the pieces in the space optimally?

Without a human-like innate ability to comprehend spatial relationship, the puzzle poses a significant challenge for machines. This type of puzzle could involve manipulating objects, visualizing rotations or transformations, or navigating through a complex environment. While humans can often intuitively grasp these concepts, machines may struggle to find an effective approach to tackle these problems without specifically designed representation, algorithms or methods that can handle spatial information.

Figure. Illustrated an example spatial reasoning domain. Questions to be answered (1) is there a solution? (2) how can we pack the space?

To engineering, when we are developing spatial reasoning algorithms presents several challenges, such as managing high-dimensional data, dealing with noisy sensor inputs, and achieving real-time performance. The spatial reasoning research is required to devise more reliable and efficient representation and algorithms that is suitable to be used by the machine.

The development of AI systems with enhanced spatial reasoning capabilities is important to comprehend their surroundings and make informed predictions about future outcomes. However, before diving into the technical challenges associated with the engineering of such a spatial reasoning system, it is essential to explore the philosophical insights that can inform its design. In the next section, we will investigate the contributions of various philosophers, whose work contributed to the nature of human spatial reasoning and cognition. By standing on the philosophical foundations of spatial reasoning, we can more effectively identify the key considerations that should guide the development of advanced AGI systems.

Philosophy and Spatial Reasoning

It’s essential to understand our cognitive abilities, which allow us to perceive, process, and act upon spatial information. Although philosophy may not directly involve engineering, its transformative ideas can influence the development principles of AGI systems that exhibit human-like spatial reasoning capabilities.

Figure. Inspired by M.C. Escher, Salvador Dalí, and Wassily Kandinsky’s styles, like fragmented landscapes, impossible structures, and dreamlike scenes (image credit: Stable Diffusion).

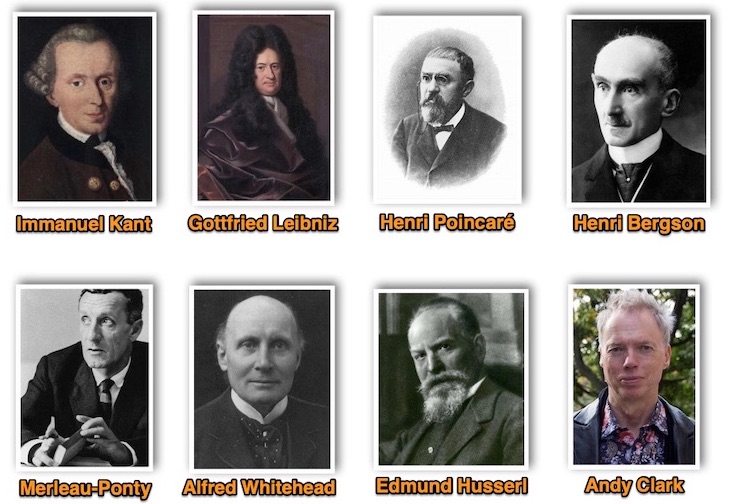

Philosopher Thoughts on Spatial Cognition & Reasoning

Here’s some examples of notable philosophers that have written about spatial cognition and reasoning:

see References for their philosopher works.

-

Immanuel Kant: In his “Critique of Pure Reason,” Kant argued that space is an a priori intuition, meaning it’s not derived from experience- but rather shapes our experiences. His ideas emphasize that spatial reasoning is a core component of human cognition.

-

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: He proposed a relational view of space, arguing that space is not an independent entity but rather a collection of relationships between objects.

-

Henri Poincaré: Made significant contributions to the philosophy of space and geometry. He argued that our spatial understanding is deeply rooted in our experiences and interactions with the world, emphasizing the role of intuition and practical knowledge.

-

Henri Bergson: His concept of “duration” highlights the importance of time and its relationship with spatial cognition. By understanding how humans perceive and process time and space, AGI developers can better design systems that can handle dynamic environments and adapt to changes over time.

-

Maurice Merleau-Ponty: Believed that our physical presence and interaction with the world shape our understanding of space. This perspective can inspire the development of AGI systems that incorporate embodied cognition, allowing them to better reason about space through direct interaction with their environments.

-

Alfred North Whitehead: Best known for his development of process philosophy. He highlights the importance of experience and perception, suggesting that our understanding of space is continuously refined through interactions with the world.

-

Edmund Husserl: Founder of phenomenology. He explored the nature of spatial objects and the role of consciousness in perceiving and constituting spatial relationships.

-

Andy Clark: Known for his work in cognitive science, specifically in areas of embodied and extended cognition. His contributions to spatial reasoning emphasize the importance of the mind extending beyond the brain, incorporating tools and external resources (such as the role of the body in interactions with the environment).

Influential Philosophical Concepts in AGI Design

By synthesizing the philosophical insights on spatial reasoning from these philosophers, we can identify several key principles and considerations for AGI design and architecture:

| Principle | Philosopher(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Emphasize embodied cognition | Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Andy Clark | Design AGI systems that incorporate the role of the body and its interaction with the environment in shaping spatial understanding and reasoning. |

| Focus on spatial relationships | Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Edmund Husserl | Prioritize understanding spatial relationships between objects in AGI design, recognizing that space is a collection of relationships rather than an independent entity. |

| Develop intuitive and practical knowledge | Henri Poincaré, Immanuel Kant | Design AGI systems that can acquire practical knowledge and intuition in spatial reasoning through experiences and interactions with the world. |

| Incorporate perception and experience | Alfred North Whitehead, Edmund Husserl | Build AGI systems that refine their understanding of space and spatial reasoning through continuous interactions with the environment and by incorporating perceptions and experiences. |

| Foster adaptability and dynamism | Henri Bergson, Henri Poincaré | Create AGI systems that can handle dynamic environments and adapt to changes over time by understanding the relationship between time and spatial cognition. |

Here’s an overview of how philosophical ideas regarding spatial understanding can be applied to AGI design.

These insights help us appreciate the complexity of spatial reasoning and its central role in our cognitive processes. It emphasizes the importance of embodied cognition, spatial relationships, intuitive and practical knowledge, perception and experience, and adaptability. By incorporating these principles into the design of AGI systems, we can work towards developing artificial general intelligence that better reflects the complexity and richness of human spatial reasoning capabilities.

Ways to Improve AGI Spatial Reasoning

AGI experts emphasize the importance of spatial reasoning for achieving Artificial General Intelligence, highlighting that overcoming the limitations of text-based LLMs requires a combination of approaches. These include multi-modal learning to integrate different data sources, embodied AI to enable interaction with the environment, reinforcement learning in simulated environments, cognitive architectures inspired by human cognition, and transfer learning to enable generalization across different spatial tasks. By adopting these approaches, AI systems may better represent and manipulate spatial information, bringing them closer to achieving AGI.

Figure. Illustrated the spatial cognitive and spatial reasoning abilities transfer from human to AI, inspired by M.C. Escher, Salvador Dalí, and Wassily Kandinsky’s styles, without spatial ability AGI will not be completed (image credit: Stable Diffusion).

While there is no existing AI system that perfectly embodies all the principles outlined from the philosophical works on spatial reasoning, there are several AI projects and systems that incorporate some of these principles to varying degrees. Some examples include:

-

Robotic systems: Many robotic systems focus on embodied cognition by interacting with their environments and processing sensory information to perform tasks like navigation, object manipulation, and scene understanding. Examples of such systems include autonomous vehicles, drones, and robotic arms used in manufacturing or research settings. These systems often use techniques like SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) and other perception algorithms to process sensory data and understand spatial relationships.

-

Reinforcement learning agents: Reinforcement learning (RL) is an AI paradigm that allows agents to learn from their interactions with the environment through trial and error. RL agents often develop intuitive and practical knowledge as they learn to navigate and interact with their environments. Projects like OpenAI’s Dactyl and DeepMind’s AlphaGo incorporate reinforcement learning to develop skills in robotic manipulation and gameplay, respectively.

-

Neural network architectures for spatial reasoning: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are examples of AI architectures that have been designed to handle spatial relationships and structures. CNNs, which have been extensively used in image recognition and computer vision tasks, are inherently designed to process spatial information in a hierarchical manner. GNNs, on the other hand, can explicitly model spatial relationships in the form of graphs, which allows them to reason about complex spatial structures.

-

Multimodal perception: AI systems that incorporate multimodal perception are designed to process and integrate sensory information from different sources, such as vision, audition, and touch. These systems can fuse information from multiple modalities to create a more comprehensive understanding of the environment. Examples include AI systems for autonomous vehicles that combine visual data from cameras with data from LIDAR and other sensors.

Although these AI systems and projects incorporate some of the outlined principles and have made significant progress, they’re still specialized and limited in their capabilities. Alternatively, we might wonder why not focus on directly enhancing the spatial reasoning abilities on LLMs. We will delve into the specifics of this approach in the subsequent section.

Enhancing Spatial Reasoning Capabilities in LLMs

Here are some possible strategies of AGI’s spatial reasoning capabilities being attained through enhancing the proficiency of large language models:

Augmenting Training Data

Large language models are trained on massive amounts of text data, and the quality and quantity of this data can significantly impact their performance.

Augmenting training data is the process of adding more data to the existing training set of a machine learning model to improve its performance on a specific task. In the context of large language models and spatial reasoning, augmenting training data could involve adding more text data that contains spatially oriented information or other spatially related data sources, such as images, maps, and diagrams.

For example, if a large language model is being trained to understand spatial relationships between objects in a city, the training data could be augmented with text data that describes the layout of the city, as well as with images or maps of the city. The augmented data could also include descriptions of spatially oriented events or activities, such as a parade or a construction project, to help the model learn how to reason about spatial relationships in dynamic environments.

One challenge with augmenting training data for spatial reasoning is that spatial relationships can be complex and difficult to represent accurately in text. However, recent advances in natural language processing and computer vision have enabled the development of techniques for automatically extracting spatially relevant information from text and images. Another challenge is that there may be limited sources of spatially oriented data available for certain tasks, particularly for niche or specialized domains. In these cases, researchers may need to create their own data sources, such as by generating synthetic text and images or by crowdsourcing annotations from human experts.

Incorporating Multi-modal Inputs

Spatial reasoning involves both visual and verbal inputs, and incorporating multimodal inputs, such as images or videos, can help large language models better understand and reason about spatial relationships.

Incorporating multimodal inputs is an approach that involves combining multiple forms of input, such as text, images, videos, or audio, to improve the performance of large language models on spatial reasoning tasks.

As an example, when asked to answer a spatial reasoning question, a large language model that incorporates multimodal inputs might be provided with an image that illustrates the spatial relationship between two objects and a textual description of the same relationship. By analyzing both the image and the text, the model can more effectively reason about the spatial relationship between the objects.

There are different approaches for incorporating multimodal inputs into large language models. One approach is to use a model architecture that can handle multiple forms of input, such as a neural network with multiple input layers. Another approach is to use a technique called attention, which allows the model to selectively focus on certain parts of the input based on their relevance to the task. It can be particularly useful for spatial reasoning tasks, as it allows the model to selectively focus on the most relevant visual and textual information. For example, attention might be used focus on the distance between the objects or their orientation, depending on the task.

Fine-tuning on Spatial Reasoning Tasks

Fine-tuning, or adapting a pre-trained model to a specific task, can improve a large language model’s performance on that task.

Fine-tuning is a technique used to adapt a pre-trained machine learning model to a specific task or domain by updating its parameters on a new set of labeled examples.

The process typically involves the following steps:

-

Pre-training: A large language model is trained on a large corpus of text data, such as Wikipedia or web pages, to learn general language patterns and structures.

-

Task-specific data collection: A smaller set of labeled data that is specific to the spatial reasoning task of interest is collected or curated. This dataset includes examples of the task, such as descriptions of spatial relationships, spatially related questions and answers, or images and videos with spatially related information.

-

Fine-tuning: The pre-trained model is updated on the task-specific data by optimizing its parameters to minimize the loss function, which measures the difference between the model’s predicted output and the true label in the task-specific data. The fine-tuning process adjusts the model’s parameters to better capture the spatial relationships in the task-specific data, improving its performance on spatial reasoning tasks.

One of the advantages of fine-tuning is that it can improve the model’s performance on specific tasks without requiring extensive retraining. Instead of starting from scratch, fine-tuning adapts the pre-trained model to the new task by adjusting its parameters to better capture the specific features of the spatial reasoning task. Fine-tuning can also be combined with other techniques, such as data augmentation or incorporating multimodal inputs, to further improve the model’s performance on spatial reasoning tasks.

Developing Novel Architectures

A model architecture that combines language processing with visual attention mechanisms could better integrate verbal and visual inputs.

One example of a novel architecture that combines language processing with visual attention mechanisms is the VisualBERT model. VisualBERT is based on the BERT architecture, which is a popular pre-trained language model that is trained on a large corpus of text data. VisualBERT extends the BERT architecture to incorporate visual attention mechanisms, allowing the model to selectively attend to relevant parts of the input image.

The visual attention mechanisms in VisualBERT operate at different levels of granularity, allowing the model to attend to both high-level features of the image, such as the overall scene, as well as lower-level features, such as specific objects or regions of interest. This enables the model to reason about spatial relationships between objects at different scales.

Another example of a novel architecture that combines language processing with visual attention mechanisms is the Visual Question Answering (VQA) model. The VQA model is designed to answer questions about an image by attending to relevant parts of the image and generating natural language descriptions of those parts.

Concluding Remarks

In summary, spatial reasoning is a crucial aspect of human cognition and plays a significant role in our ability to interact with, understand, and navigate the complex, dynamic world around us. To develop AGI systems that exhibit human-like intelligence, it is essential to incorporate spatial reasoning capabilities that reflect the richness and complexity of human spatial cognition.

Drawing from the insights of philosophers who have contributed to our understanding of spatial reasoning, several key principles can inform AGI design and system architecture:

- Emphasize embodied cognition, allowing AGI systems to interact with their environments and process sensory information.

- Focus on spatial relationships and develop algorithms capable of representing, learning, and reasoning about spatial structures.

- Encourage the development of intuitive and practical knowledge through experience and interaction with the environment, possibly incorporating unsupervised learning or reinforcement learning techniques.

- Incorporate perception and experience by designing AGI systems that can process and integrate sensory information from various sources, enabling a comprehensive understanding of the environment.

- Foster adaptability and dynamism, equipping AGI systems to handle changing environments and evolving spatial relationships.

Although no current AI system, including LLM, fully encompasses all of these principles, numerous projects and systems have advanced by adopting some of them. These researches showcase the promise of integrating spatial reasoning abilities into AI systems, ultimately moving us nearer to the objective of artificial general intelligence. In the future, we shall be developing more articles that delve into the technical aspects of building such a system.

References

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)

The recent paper published by Microsoft Research illustrated the surprising AGI potential of GPT-4:

- Sebastien Bubeck, et. al., Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4, arXiv:2303.12712, Microsoft Research, Mar 22, 2023.

There are several books on Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) that you can read. Here are some of the best ones:

- Nick Bostrom, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies, Oxford University Press, Apr 2016. ISBN:978-0198739838

- Stuart Russell, Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control, Penguin Books, Nov 2020. ISBN:978-0525558637

The Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) classic book (even it is very old):

- Goertzel, Ben, and Cassio Pennachin, Artificial General Intelligence (Cognitive Technologies), Vol. 1. Springer, 2007. ISBN:978-3642062674

Spatial Reasoning

- Sabine Hossenfelder, I believe chatbots understand part of what they say. Let me explain, video, Mar 2023.

- When she described an example of “What’s goes up must come down” and the latitude example of “Toronto CA vs Windsor UK latitude” location, both example illustrated the important aspect of ChatGPT is missing the spatial relationship understanding. It does not have a spatial model of the world.

- Renz, Jochen. Qualitative Spatial Reasoning with Topological Information. Vol. 1. Springer, 2002. ISBN: 978-3540433460

- Aiello, Marco, Ian Pratt-Hartmann, and J. F. A. K. van Benthem. Handbook of Spatial Logics. Vol. 1. Springer, 2007. ISBN: 978-1-4020-5586-7

Philosophy on Spatial Cognition and Reasoning

Immanuel Kant’s philosophy work:

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s philosophy work:

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz - Wikipedia

Henri Poincaré’s philosophy works related to spatial reasoning:

Henri Bergson’s philosophy related to spatial reasoning:

Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy works related to spatial cognition and reasoning:

Alfred North Whitehead’s philosophy works related to spatial cognition and reasoning:

Edmund Husserl’s philosophy works related to spatial reasoning:

- The Phenomenology of Internal Time-Consciousness

- Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy

- The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology

Andy Clark’s philosophy works related to spatial cognition and reasoning:

- Embodied Cognition and the Magical Future of Interaction Design

- Natural-Born Cyborgs: Minds, Technologies, and the Future of Human Intelligence

- Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again

Related Posts on Spatial Reasoning

- Benny Cheung, Spatial Reasoning Explained, Benny’s Mind Hack, Jun 2016.

- Benny Cheung, Model of Spatial Construction, Benny’s Mind Hack, Jul 2016.

- Benny Cheung, Geospatial Granular Computing, Benny’s Mind Hack, Dec 2018.