artwork by Gemini 3 Pro

GameGrammar - The Theory of Generative Board Game Design

Game Architecture

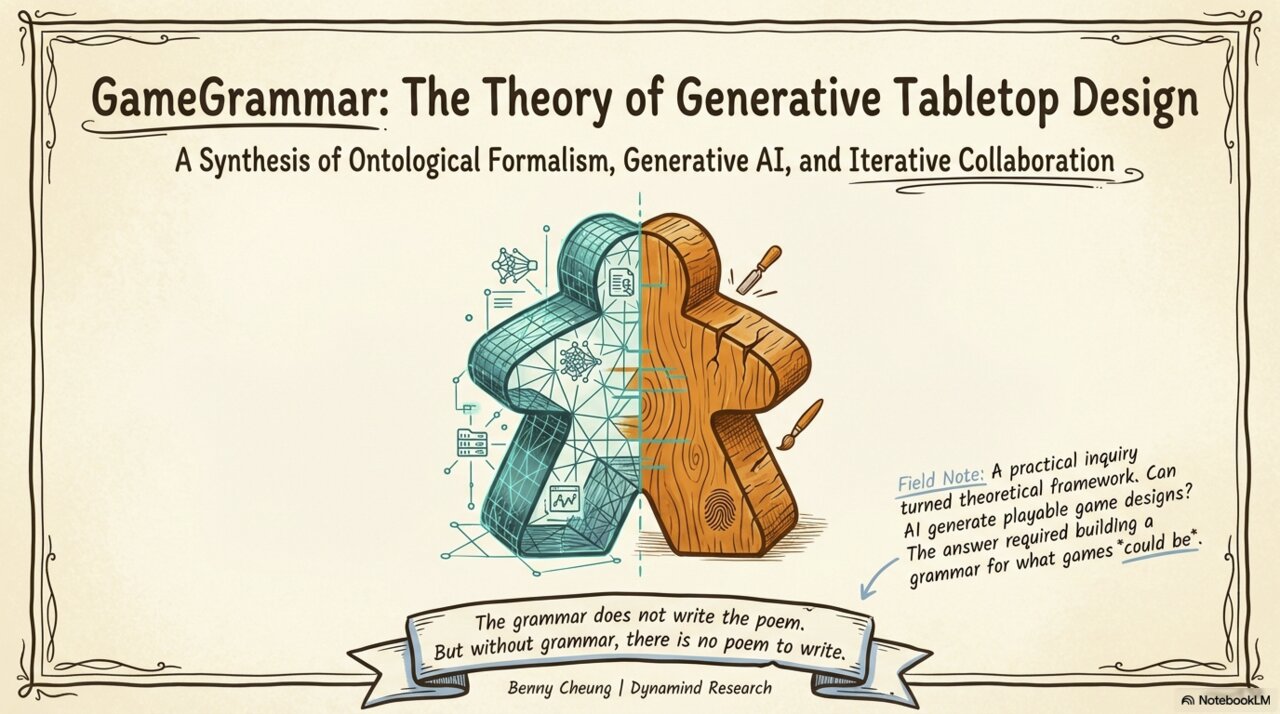

Part 6 of 7A poet needs grammar. A game designer needs structure. This article lays out the design theory behind GameGrammar, a theory born from one practical question: Can AI help create playable board games? The answer turned out to require more than clever prompting. It required a shared vocabulary for what games are, a way to generate what games could be, and a collaborative process for refining what games should become. What follows is that theory, and a direct answer to two questions every designer asks: Can AI really understand “fun”? And can AI be genuinely creative?

Figure. Structure meets imagination. The left half shows the blueprint, the right half shows the finished piece. GameGrammar bridges both worlds.

GameGrammar did not begin as a theory. It began as a practical experiment at Dynamind Research [7]: type a theme into a box, let six AI agents build a complete board game, and see what comes out. What came out, after months of iteration, was not just a tool but a set of ideas about how design works, why AI can be a trustworthy creative partner, and what that means for human designers.

In a previous article, we showed what GameGrammar produces: twelve words in, a complete game out in 73 seconds. This article goes deeper. It explains the why behind the what, the design thinking that makes human-AI game design not just possible, but genuinely new.

Where GameGrammar Fits: The Board Game Production Pipeline

Before we explore the ideas, it helps to understand where GameGrammar sits in a game designer’s workflow. The journey from idea to published box on a shelf is a nine-stage pipeline, and most people only see the last few stages [7]:

| Stage | Phase | What Happens |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Concept & Early Design | Core idea, initial mechanics, paper prototype |

| 2 | Iterative Playtesting | Cut, merge, rewrite rules; stress-test systems |

| 3-9 | Design Lock through Post-Launch | Development, art, manufacturing, marketing, distribution, support |

The graveyard is in Stages 1 and 2. This is where designers spend the most time, where most “cool mechanics” die (and should), and where motivation quietly erodes. The blank page is the first enemy. Before you can even begin the playtesting gauntlet, you need a concept worth testing: not just a theme, but a coherent combination of mechanics, components, player dynamics, and victory conditions.

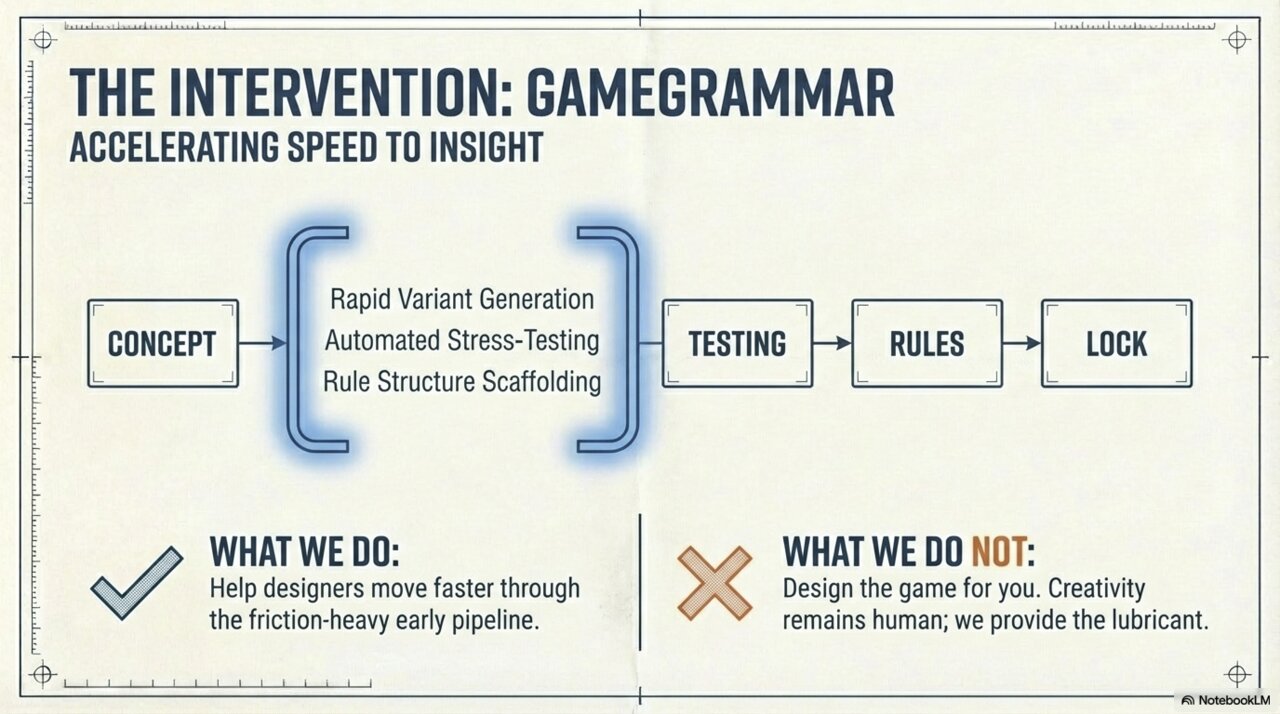

Figure. GameGrammar sits between Concept and Testing, providing rapid variant generation, automated stress-testing, and rule structure scaffolding. It helps designers move faster through the friction-heavy early pipeline, but does not design the game for you.

GameGrammar lives at Stages 1 and 2. It is a design workbench for the earliest and most uncertain phases of game creation:

- Stage 1: Generate structured first drafts from a theme and constraints. Beat blank-page paralysis. Explore mechanism combinations drawn from real published games.

- Stage 2: Iterate rapidly with AI-assisted consistency checking, balance analysis, section-by-section rewriting, and plain-language editing. Catch issues that would normally take weeks of playtesting to surface.

GameGrammar does not touch Stages 3 through 9. It will not lock your design, pitch to publishers, produce art, or manage manufacturing. It sits precisely where you need the most help and where AI can do the most good: turning a theme into a testable design, and helping you refine that design through structured iteration.

The positioning matters. GameGrammar is a design accelerator that helps you move faster through the early pipeline. It is not a replacement for your craft. You remain the designer. The AI is your instrument.

The Core Idea

Game design is a structured creative act. It can be broken into a shared vocabulary of game elements, powered by AI generation, and refined through back-and-forth collaboration between human and machine. The result is something neither purely human nor purely AI, but a co-designed partnership that plays to the strengths of both.

This idea rests on three observations:

-

Games share a common structure. Beneath the surface diversity of tabletop games lies a shared language: mechanisms, components, player dynamics, turn structures, scoring systems. That language can be captured in useful detail.

-

Structure makes generation possible. When you encode that language as a detailed template, AI can generate within it. The template becomes a grammar that enables valid, coherent, novel designs, not by limiting creativity, but by giving it a vocabulary to be creative within.

-

Design is iterative, not instantaneous. No generated design is finished. The real work happens in the refinement loop: spotting contradictions, updating connected sections, rewriting what has gone stale, translating your intent into concrete changes. This loop needs your judgment, guided by AI analysis.

Why Constraints Enable Creativity

The theory starts with a paradox familiar to many designers. Without structure, there is no coherent creation.

A poet needs grammar. A game designer needs structure.

If you ask a general-purpose AI to “design a board game,” you get fluent, confident text that falls apart the moment you try to prototype it. No concrete card counts. No defined end condition. No actual scoring math. The structured vocabulary that GameGrammar uses is what makes valid generation possible. The constraints do not limit creativity. They are the reason creativity can happen.

Think of it this way: most game design vocabularies describe what games are. GameGrammar’s vocabulary creates what games could be. By capturing game design knowledge as a detailed template, with required fields, defined mechanism categories, and relationships between parts, we turn a passive description into a generative starting point. The template says: every game must have a goal, an end condition, mechanisms that create player choices, and components that bring those mechanisms to life. Within those boundaries, infinite games are possible. Without them, no valid game comes out.

The Philosophical Thread

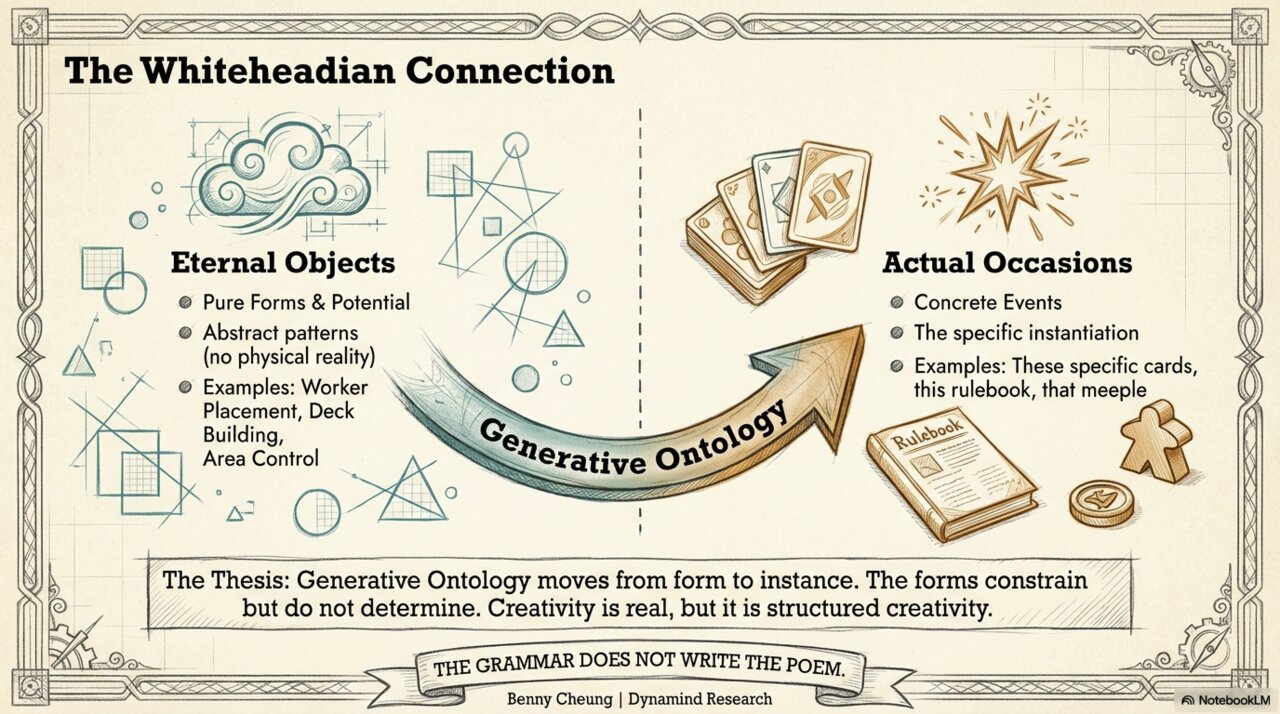

There is a philosophical idea running beneath all of this, drawn from Alfred North Whitehead’s process philosophy [1][2], which we explored in depth in a previous article. The key distinction is between abstract patterns (like worker placement, deck building, or area control as general concepts) and concrete games (where those patterns become specific cards, tokens, rules, and boards).

Figure. Abstract patterns become concrete games. The patterns constrain but do not determine. The creativity is real, but it is structured creativity.

GameGrammar’s job is to move from abstract patterns to concrete games. The vocabulary provides the patterns; AI generation produces the specific instances. Each generated game is genuinely new, a fresh combination of familiar building blocks arranged in a way that did not exist before.

Bridging Structure and Imagination

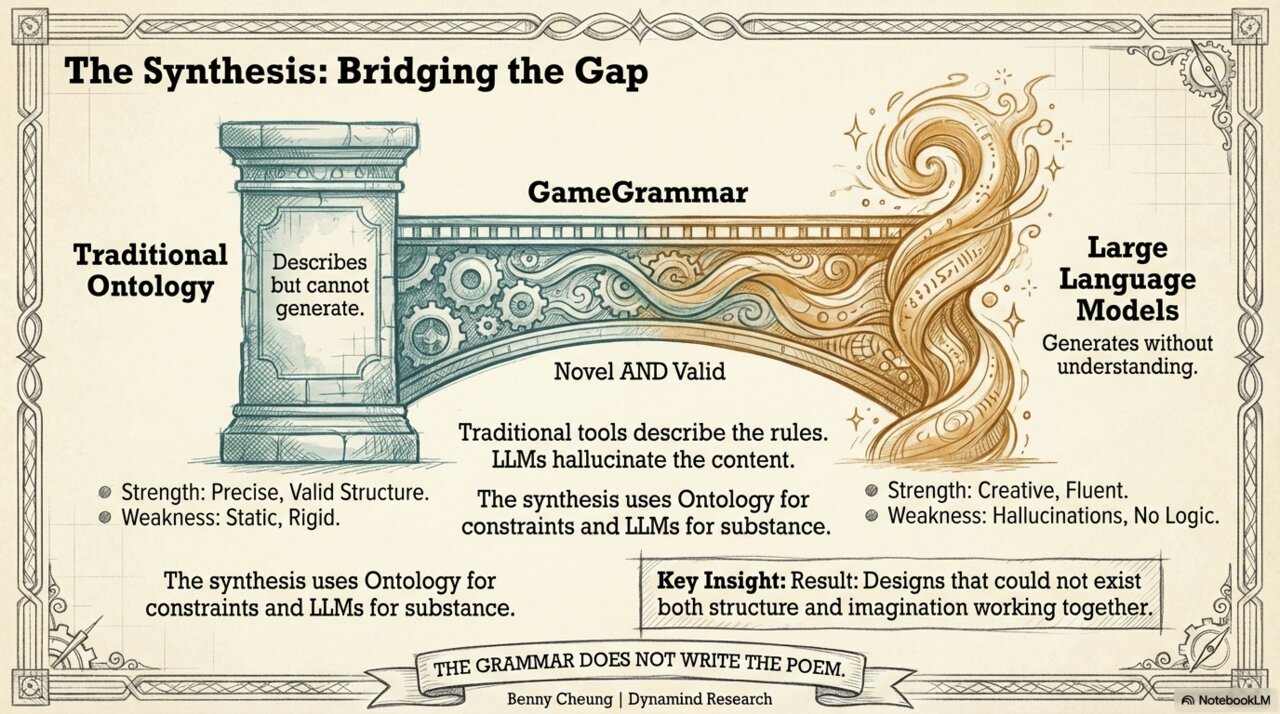

Structure and imagination have opposite strengths:

| Structured Vocabulary | AI Generation | |

|---|---|---|

| Strength | Precise, valid, complete | Creative, fluent, novel |

| Weakness | Cannot create new designs | Creates without structural understanding |

Figure. GameGrammar brings together what structure and imagination each do best. The result is designs that are both novel and valid, something that could not exist without both halves working together.

GameGrammar combines both. The structured vocabulary provides the constraints; the AI provides the creative substance. The result is designs that could not come from either half alone.

The Six-Agent Pipeline

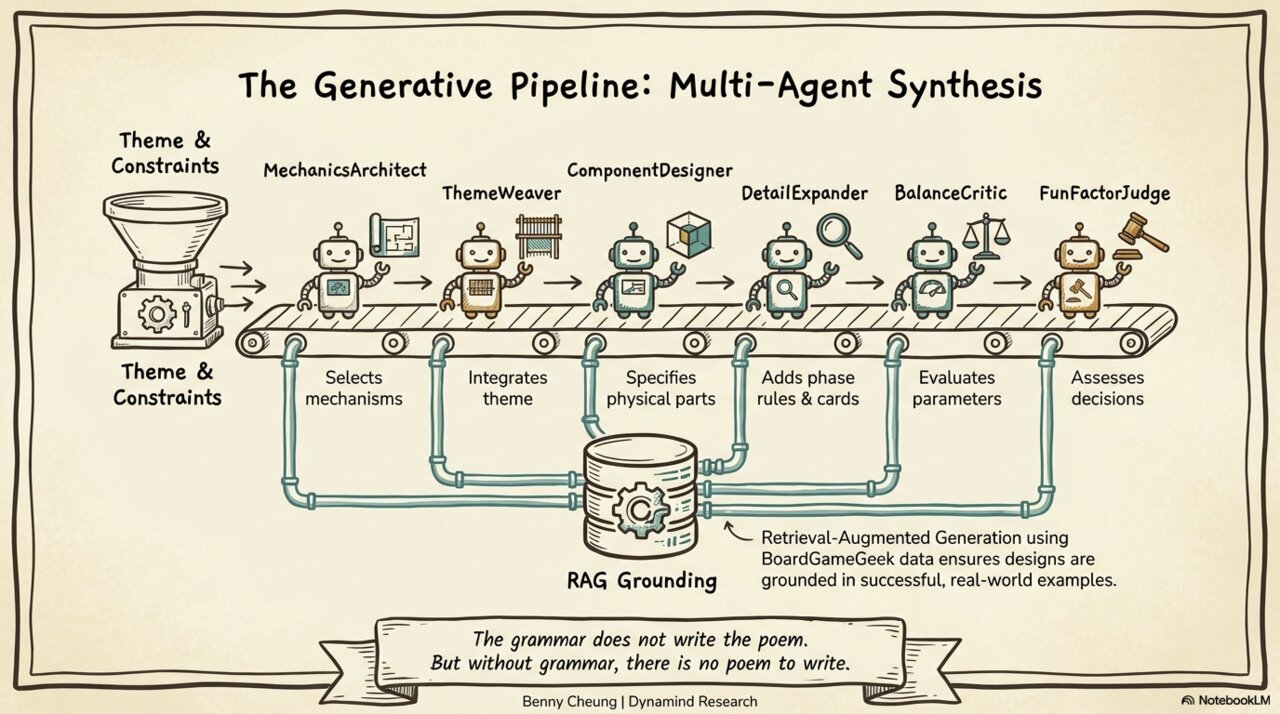

Generation is not a single AI prompt. It is a team of six specialized agents, each focused on one area of game design [7]:

Figure. Six specialized agents working in sequence. Each agent sees the complete output of all previous agents, building on their work like a relay team of expert consultants.

The Mechanics Architect picks mechanisms from a curated library of 35 game mechanisms drawn from Engelstein and Shalev’s taxonomy [3]. The Theme Weaver dresses the mechanics in your theme. The Component Designer specifies every physical piece with concrete counts. The Detail Expander writes out turn phases, card examples, and scoring rules. The Balance Critic flags potential issues in the numbers. The Design Evaluator scores six dimensions of design quality, maps the emotional arc across game phases, and measures how original your mechanism combination is. You get a creative profile, not just a single rating.

Grounded in Real Games

Generated designs are not invented from thin air. GameGrammar draws on a reference library of 2000+ existing games from BoardGameGeek [6]. When generating a worker placement game, the system looks at successful worker placement designs, their component counts, player counts, mechanism pairings, and balance approaches, and uses them as guideposts for your new design. This keeps generated games grounded in patterns that have proven themselves in published, well-regarded games.

The same reference library serves a second purpose: measuring originality. After generation, your design’s mechanism combination is compared against the full collection of existing games. This produces a novelty score. “Your combination of worker placement plus real-time resolution appears in only 3% of reference games.” It is consistent, explainable, and genuinely rewarding when you discover you are exploring uncharted design territory.

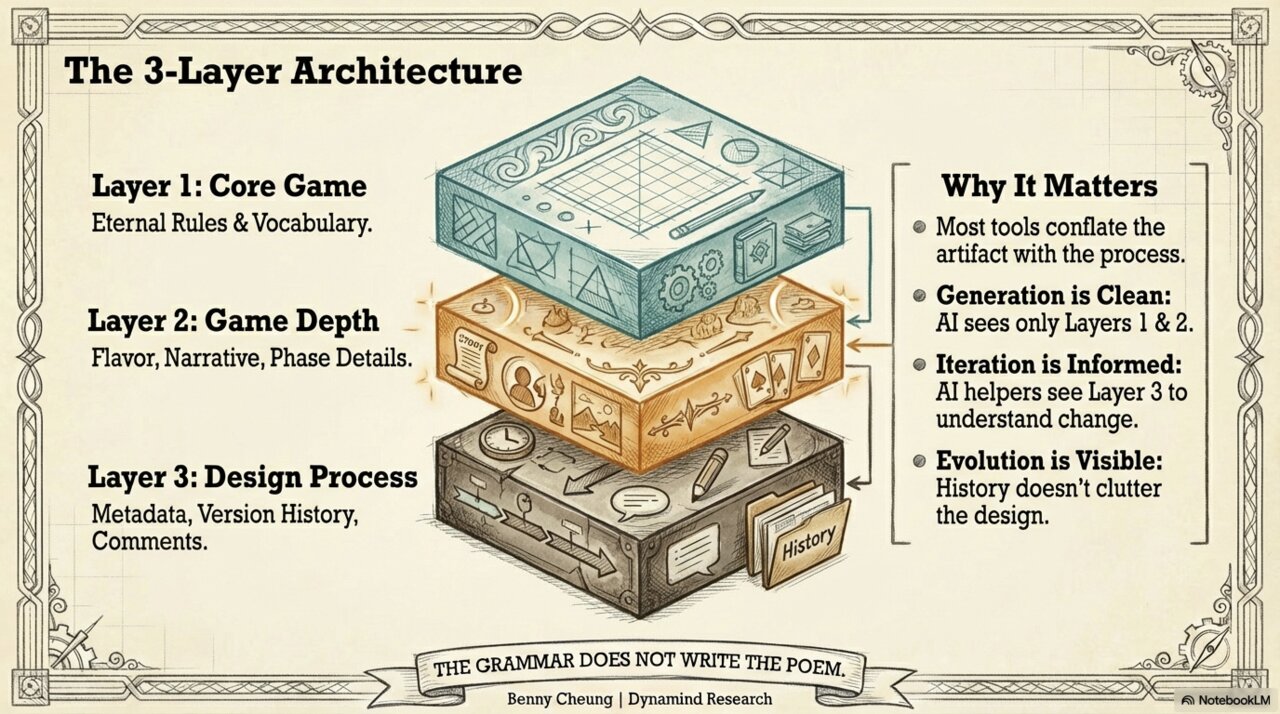

Three Layers: Game, Depth, and Process

Your game design in GameGrammar lives on three separate layers, and keeping them separate turned out to be one of the more useful design decisions we made. This separation is not just convenient engineering. It follows directly from the distinction between abstract patterns and concrete instances described earlier. The game itself (Layer 1) holds the patterns. The details (Layer 2) hold the concrete instances. The process (Layer 3) holds the history of how one became the other.

Figure. Three layers keep generation clean, editing informed, and your design’s evolution visible. Most design tools mix the game with the process of making it. GameGrammar separates them.

Layer 1, Your Game, captures the building blocks of any tabletop game: mechanisms, components, turn structure, player dynamics, scoring. These are the abstract patterns, the eternal building blocks that exist across all games, whether you are designing a quick party game or a sprawling civilization epic.

Layer 2, The Details, is where patterns become this specific game. Concrete specifics: what actually happens during each turn phase, example card text, scoring formulas with real numbers. This is the difference between “this game has a drafting phase” and “in the drafting phase, each player picks one card from a shared pool of 5, resolving simultaneously.”

Layer 3, The Design Process, captures something traditional design tools ignore entirely. If you have ever maintained a game design in a shared Google doc, with crossed-out rules, margin notes that contradict each other, and version 14 saved as “final_FINAL_v2”… you know the pain. Layer 3 solves it. It tracks which sections need updating after your changes, flags consistency issues before you discover them in playtesting, holds AI suggestions you have saved for later, and maintains a full version history with comparison and rollback. It is the organized contractor’s clipboard that keeps the renovation from becoming chaos.

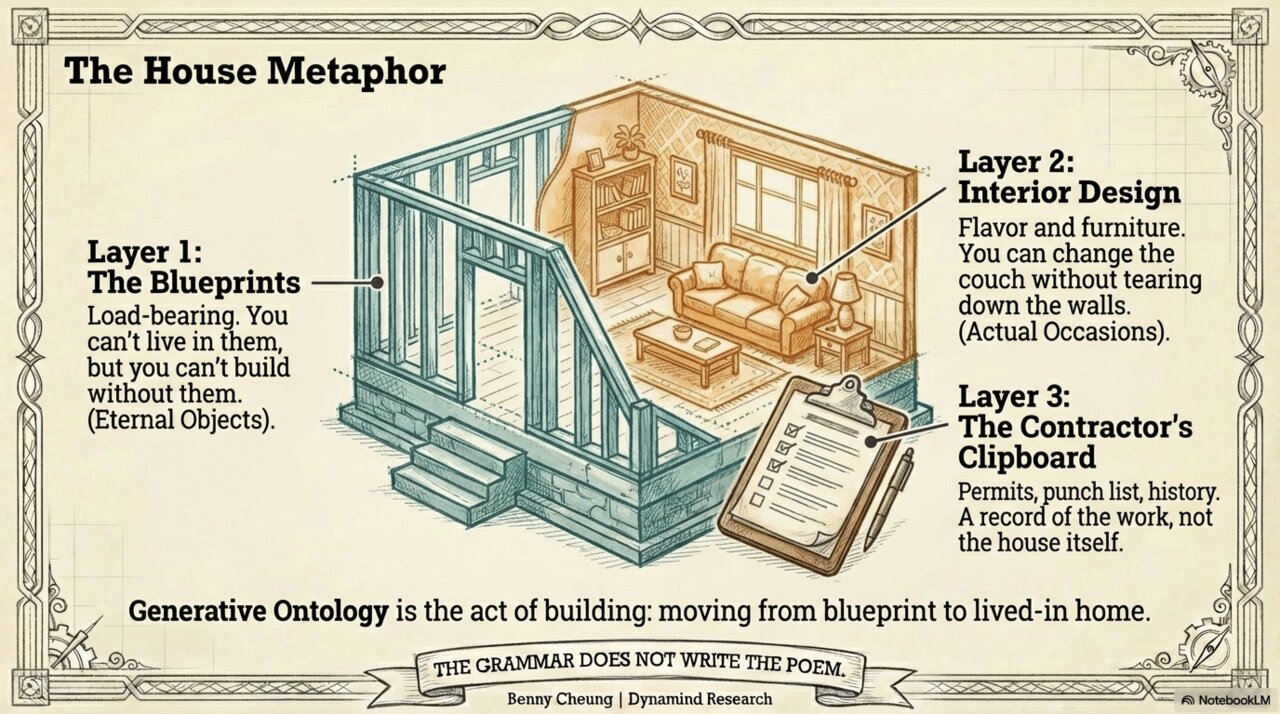

The House Metaphor

Think of it like building a house:

Figure. Layer 1 is the blueprints. Layer 2 is the interior design. Layer 3 is the contractor’s clipboard.

Layer 1 is the blueprints: foundation and load-bearing walls. You cannot live in them, but you cannot build without them. Layer 2 is the interior design: furniture and paint. You can swap the couch without tearing down walls. Layer 3 is the contractor’s clipboard: the punch list, renovation history, and building permits. A record of the work being done, not the building itself.

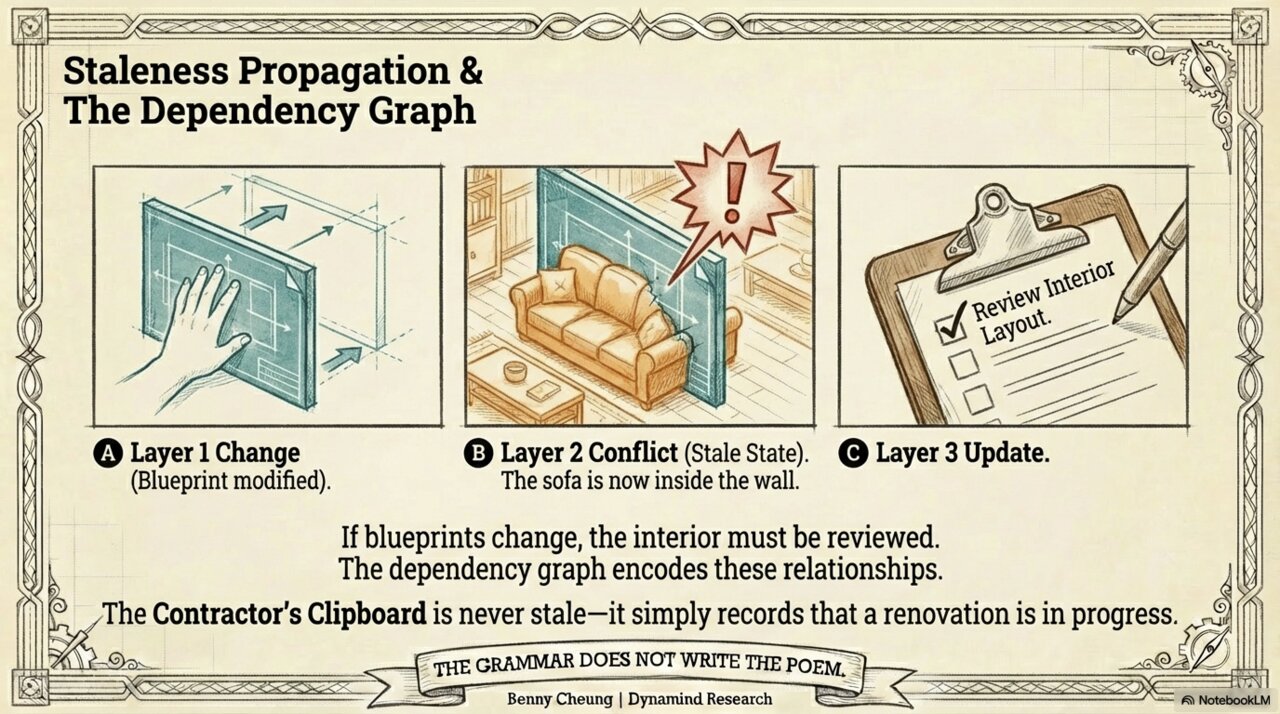

This metaphor also explains what happens when you make a big change. If you move a load-bearing wall (change a core mechanism), the furniture layout becomes outdated: the sofa is now halfway through a wall. GameGrammar tracks these connections automatically.

Figure. When you change the blueprints, the interior needs reviewing. The contractor’s clipboard is never outdated; it just records that renovation is underway.

Say you change your hand limit from seven cards to three. Suddenly your drafting phase description is wrong, your “discard to activate” power needs rebalancing, and your endgame scoring assumes players have cards they can no longer hold. In a traditional design doc, you might not catch these ripple effects for weeks. Layer 3 flags every affected section immediately.

Here is what happens next. You open GameGrammar and see three sections marked stale: Drafting Phase, Card Powers, and Endgame Scoring. You click Drafting Phase. The AI shows you the problem: “Players draft from a pool of 5, but with a hand limit of 3, they can only keep 3 cards total. The drafting round either ends too early or forces repeated discards.” It proposes two options: reduce the draft pool to 3, or let players draft then discard down. You pick the second option because you want the tension of choosing what to keep. You preview the rewritten section, adjust one sentence, and apply.

The card powers section updates next, and the AI flags that “discard to activate” now competes directly with your hand limit. It suggests making activation free for one card per turn. You disagree. That tension is the whole point of your game. You dismiss the suggestion and mark the section as reviewed.

Endgame scoring needs a number change: the bonus for “most cards in hand” no longer makes sense at three cards. You accept the AI’s proposal to replace it with “most sets completed.”

Three sections, five minutes, done. In your old workflow, you might have caught the drafting issue in your next playtest, the scoring issue two playtests after that, and the card power conflict never.

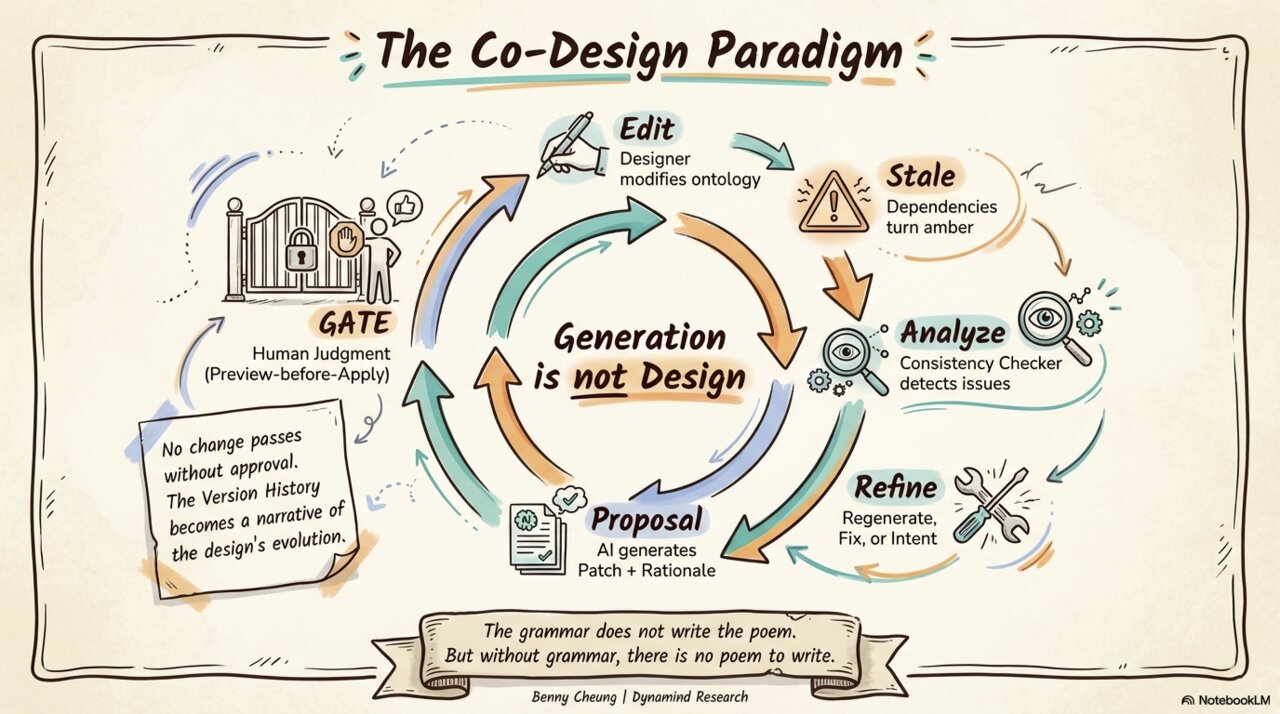

The Co-Design Partnership: Generation Is Not Design

Here is the most important insight behind GameGrammar: generating a game is not the same as designing one. A generated first draft, no matter how good, is a starting point. The real design happens in the back-and-forth that follows.

Figure. The co-design loop: you edit, connected sections update, the AI spots emerging issues, you choose how to refine, changes get versioned. Generation sits at the center, but design lives in the cycle around it.

After your first draft is generated, the design enters a continuous refinement cycle. You make changes. Connected sections get flagged for review. The AI spots contradictions and emerging issues. You choose a path forward. The AI proposes solutions with clear reasoning. You preview everything before it touches your design. You accept, modify, or reject. Your evaluation scores update, showing which dimensions improved and which declined. The cycle continues.

One rule is absolute: the AI never changes your design without your permission. Every modification follows a preview-before-apply pattern. The AI shows you what it wants to change and why. You decide. This is not just a convenience feature. It follows from the theory’s core claim: generation is not design. If the AI could just change things, it would be designing. The preview step is what keeps the human in the designer’s chair.

AI proposes. You decide.

Think of it this way: the AI is a mechanic, not a mystic. It can tell you that your engine has a misfire, that your cooperative game has conflicting competitive scoring. But it cannot tell you whether the rumble of that misfire is exactly the tension you intended. It reads the blueprint. You read the room.

Five Ways the AI Can Help

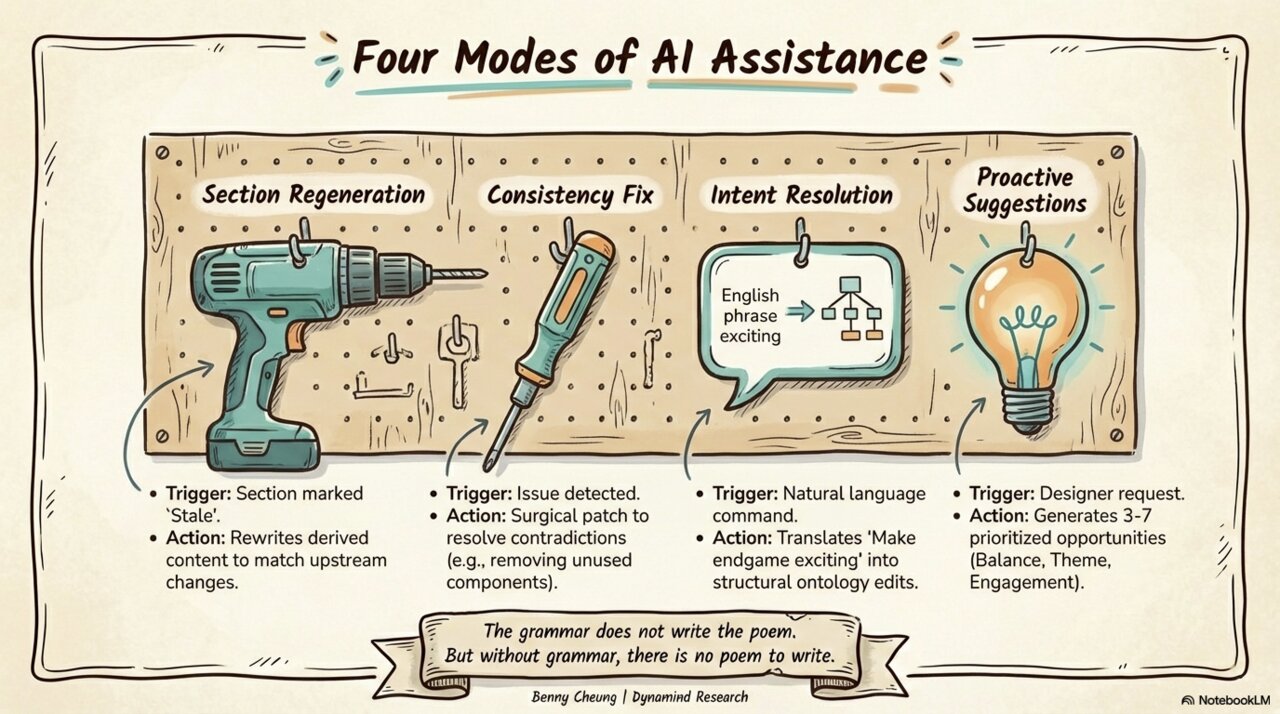

The partnership offers five distinct modes of assistance, each suited to different moments in your design process:

Figure. From precise fixes to open-ended creative guidance. You choose which mode fits your current need.

| Mode | What the AI Does | Your Role |

|---|---|---|

| Rewrite Section | Rewrites one outdated section using your current full design as context | Review and accept or reject |

| Fix Contradiction | Proposes a targeted fix for a specific inconsistency | Preview the change, confirm or skip |

| AI Edit | Translates your plain-language instruction into concrete design changes | Review what it changed, pick which parts to keep |

| AI Suggestions | Generates 3-7 improvement ideas with priorities and reasoning | Apply now, save for later, or dismiss |

| Re-Evaluate | Scores 6 design dimensions, maps the emotional arc, measures originality | Study the profile, find weak spots, decide what to improve |

Re-evaluation is especially powerful because it closes the feedback loop. After making changes through any of the other modes, you can re-score your design and see what moved. Dimensions that improved flash green; those that declined flash amber. This turns the cycle from “edit and hope” into “edit, measure, and iterate with direction.”

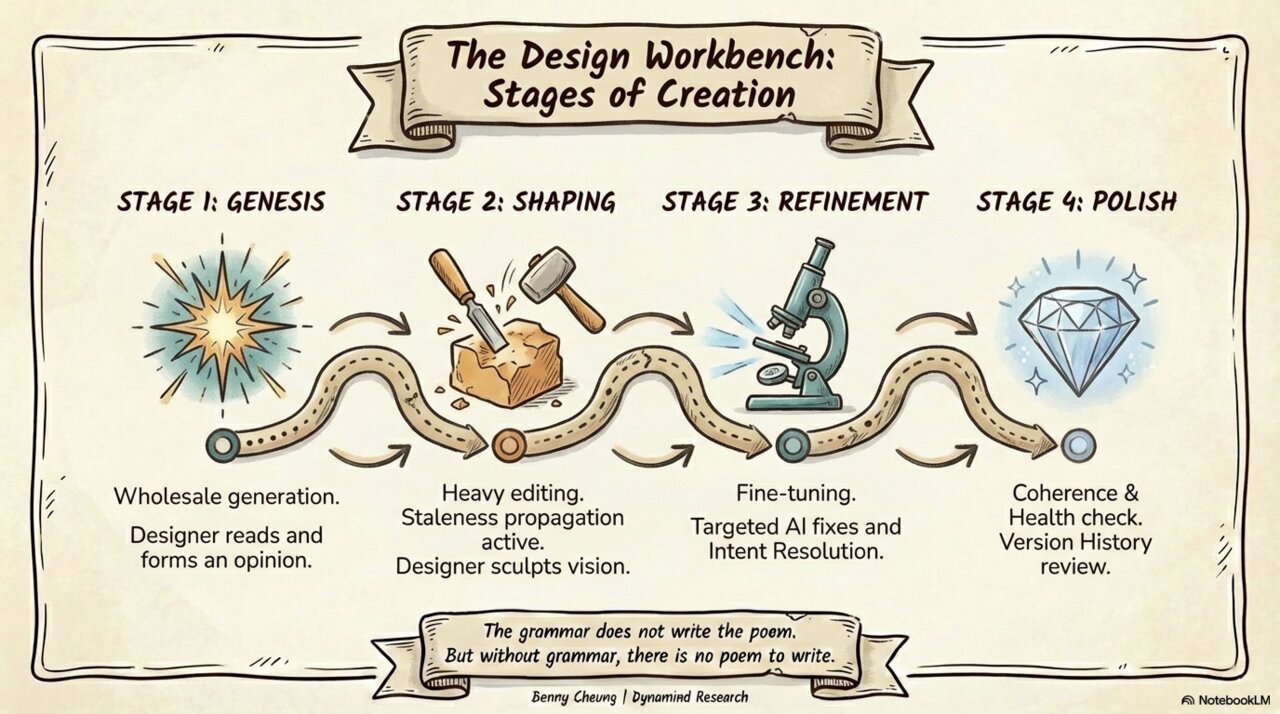

Your Design Workbench: Four Stages of Creation

A game design in GameGrammar moves through four recognizable stages, each with its own rhythm and its own set of AI tools:

Figure. Four stages from first draft to final polish. The workbench is fluid: you move between stages as the design evolves.

Stage 1, Genesis. You provide a theme, some constraints (player count, complexity, play time), and optionally pick a few mechanisms you want to include. The six-agent pipeline generates your complete first draft. You receive a full game design with a creative profile: six scored design dimensions displayed as a radar chart, an emotional arc across game phases, a theme cohesion score, and an originality percentile.

Stage 2, Shaping. You start editing. Swapping mechanisms, adjusting numbers, reworking the turn structure. Each change flags connected sections that may need updating. The AI helps with change tracking, section rewrites, and consistency checking.

Stage 3, Refinement. The big decisions are made. Now you fine-tune: adjusting balance, clarifying card effects, tightening scoring. AI assistance shifts to targeted fixes, plain-language editing (“make the hand limit 7 instead of 5”), and proactive suggestions for improvements you might not have considered.

Stage 4, Polish. Your game works. Now you focus on coherence, theme integration, and overall quality. The Creative Coach dashboard gives you the complete picture at a glance: your radar chart, originality score, theme cohesion, and emotional arc.

These stages are not a rigid sequence. You might be fine-tuning in Stage 3 when a mechanism swap sends you back to Stage 2. You might spot a weak dimension on your radar chart in Stage 4 that sparks a whole new direction. The workbench moves with you.

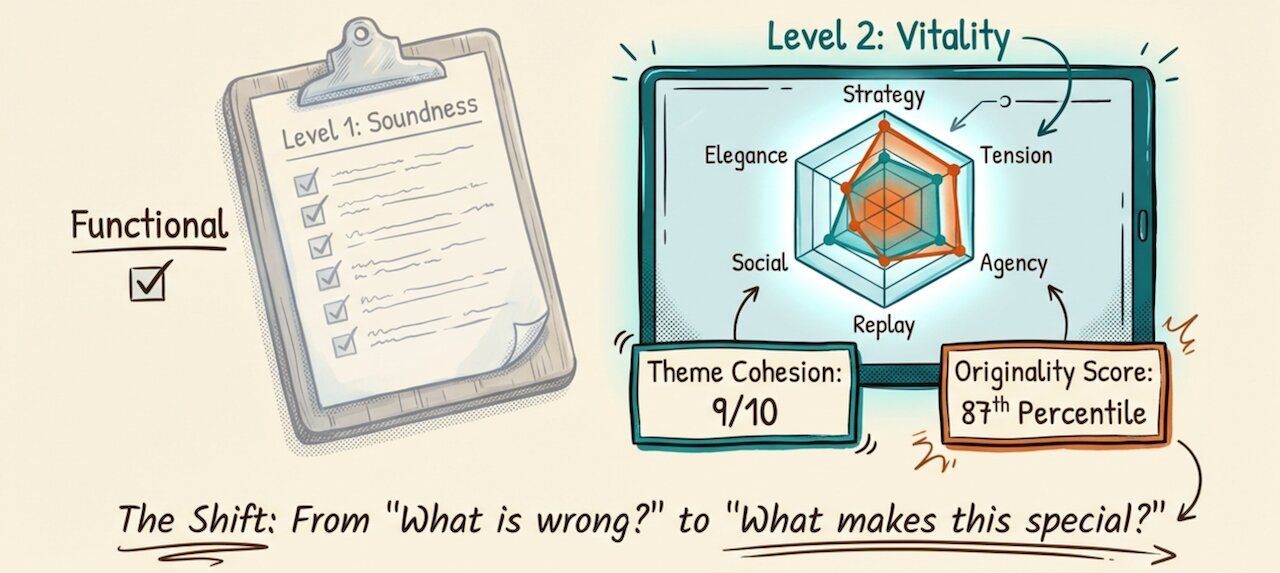

Design Health: From Bug Checker to Creative Coach

Early versions of GameGrammar’s health system only measured what was wrong with a design: contradictions, outdated sections, unresolved suggestions. Those checks are useful, but they answer the wrong question. A game with zero contradictions is functional. It is not necessarily good.

Figure. Level 1 is the clipboard: structural soundness, the checklist that confirms nothing is broken. Level 2 is the radar chart: creative vitality, the profile that shows what makes your design special. The shift is from “What is wrong?” to “What makes this special?”

The deeper insight: as a designer, you need to know not just whether the blueprint is structurally sound, but whether the game has soul. We needed to move from “nothing is broken” to “here is what makes this design special.”

GameGrammar now tracks your design on two levels:

Level 1, Structural Soundness (the floor, not the ceiling): consistency score, outdated section count, unresolved suggestions. Necessary housekeeping, but not what gets you excited.

Level 2, Creative Vitality (what you actually care about):

| Metric | What It Tells You |

|---|---|

| Six Design Dimensions | How your game scores on strategic depth, tension, player agency, replayability, social interaction, and elegance, displayed as a radar chart |

| Originality Score | How unique your mechanism combination is compared to 2000+ existing games (0-100 percentile) |

| Theme Cohesion | How well your theme, mechanics, and components hold together as a unified experience (1-10) |

| Engagement Curve | The emotional peaks and valleys players experience across your game’s phases |

The six dimensions turn the vague question “is this fun?” into actionable creative directions. Instead of a single number, you see where your design is strong and where it could grow. Strategic depth might be a 9 while social interaction sits at a 4, and that is perfectly fine if you are designing a solo puzzle game.

The Originality Score gives you a creative thrill by showing how your mechanism combination compares to published games. A score of 87 means “only 13% of existing games share this combination.” It rewards you for venturing into unexplored design space.

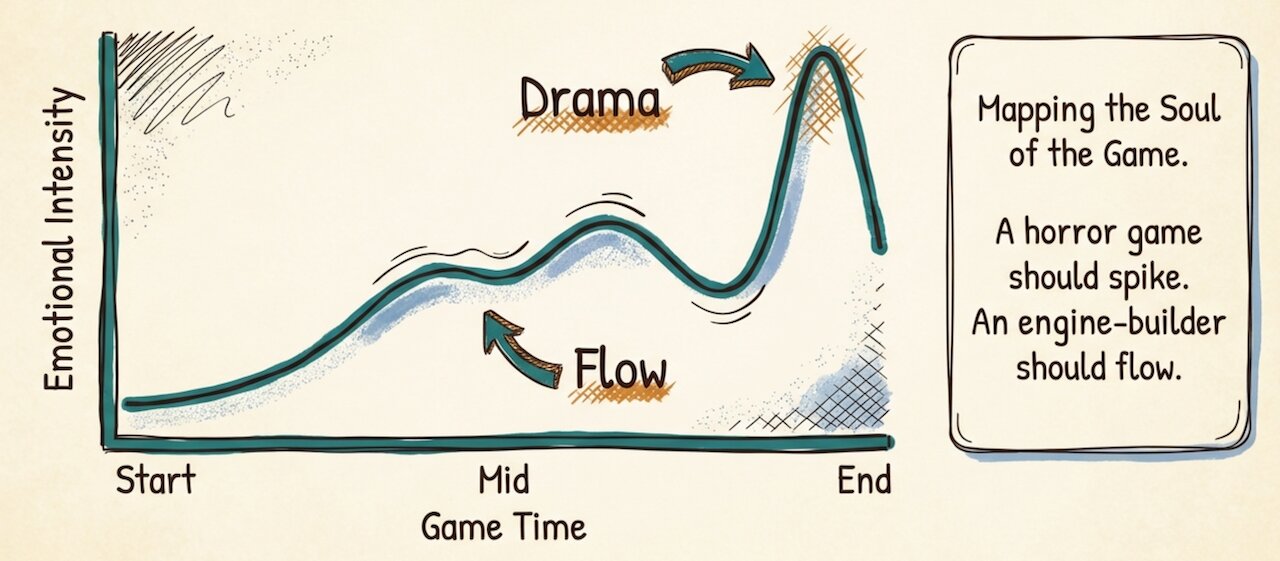

Figure. Mapping the soul of the game. The dramatic curve spikes toward the end. The flowing curve builds steadily. Neither is wrong. The curve shows what your game does emotionally, not what it should do.

The Engagement Curve maps the emotional arc of your game across its phases. A flat line suggests a one-note experience; peaks and valleys suggest drama. A horror game should spike. A meditative engine-builder should flow smoothly. But a flat curve is not automatically a problem. Some of the best engine-building games have a slow, meditative build by design. The curve shows you what your game does emotionally. Whether that matches your intention is your call, not the AI’s.

These metrics are not report cards. A low social interaction score is not a failing grade. Your game might not need social interaction. The dashboard answers “What makes this design special?” not “What is wrong?”

Can AI Understand “Fun”?

This is the question every designer asks, and it deserves a straight answer.

Figure. AI cannot feel fun, but it can recognize the patterns that cause it. Hidden info creates tension. Multiple options create agency. Escalating stakes create drama.

The short answer: no, AI cannot experience fun. It has never felt the excitement of a close finish, the satisfaction of a clever combo, or the social electricity of pulling off a bluff. It has no taste. It has no feelings.

But here is the thing: you do not need to feel fun to recognize the design patterns that produce it.

Fun in board games is not random magic. It comes from choices you make as a designer:

| What You Design | What Players Feel | Can AI Detect It? |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple real options each turn | Agency, meaningful choice | Yes, from your turn structure |

| Hidden information between players | Tension, suspense | Yes, from your mechanism choices |

| Escalating stakes toward the endgame | Drama, narrative arc | Yes, as the engagement curve |

| Few rules that create many strategies | Elegance, “easy to learn, hard to master” | Yes, by comparing rule count to strategic depth |

| Actions that directly affect other players | Social interaction, negotiation | Yes, from mechanism analysis |

| Unusual mechanism combinations | Novelty, surprise | Yes, by comparison to existing games |

A bridge engineer does not need to “feel beauty” to know the math that makes a bridge elegant. A music teacher can explain why a chord progression creates tension and release without weeping every time they hear it. Analysis and experience operate on different levels.

But here is what the analogy misses: a bridge has one purpose. A board game has as many purposes as it has players. The same mechanic that creates delicious tension for one group might fall flat for another. The AI can analyze the structural ingredients of fun (meaningful choices, hidden information, escalating stakes) but it cannot predict the alchemy that happens when four friends sit down together on a Friday night. That alchemy is yours.

There are parts of fun that stay irreducibly personal: the chemistry of your play group, the cultural resonance of a theme, the satisfying weight of wooden tokens in your hand, the occasional magic that defies explanation. AI cannot evaluate those. This is exactly why the ground rule exists: AI proposes, you decide. The AI provides structural analysis. You decide whether it matters for this game and this group of players.

The useful question is not “Can AI understand fun?” but “Can AI spot the design patterns that tend to produce fun, so you can focus your energy on the parts only a human designer can provide?” The answer to the first is no. The answer to the second is yes, and that is the only question that matters for a design tool.

Is AI “Creative”?

A related question: Can AI be genuinely creative, or does it just shuffle existing ideas around? This question is about generation, not evaluation, and it has a surprisingly good answer.

Figure. Existing elements become novel structures through synthesis. The human provides intention (the why). The AI provides recombination (the how).

The philosopher Whitehead defined creativity not as making something from nothing, but as the novel combination of existing elements [1]. Every creative act borrows from what came before but achieves something new in how it brings those pieces together. A poet inherits language, meter, and tradition; the poem is new. An architect inherits materials, engineering, and precedent; the building is new. Creativity is not the absence of inheritance. It is the fresh synthesis of what you have inherited.

This is exactly what GameGrammar does. The vocabulary provides the inherited building blocks of game design: worker placement, deck building, area control, set collection, hidden bidding. These patterns have been discovered, tested, and refined across thousands of published games. The AI generates a specific new game that combines those building blocks in a configuration that did not previously exist.

The criticism that “AI just recombines” is fair, but consider: much of human game design works the same way. Catan combined resource trading with hex grids and dice production: three familiar patterns, one landmark game. Dominion combined deck building with card drafting. Root combined area control with asymmetric player powers. A great deal of creativity in game design comes from the novel recombination of known mechanisms [3]. The difference is that human designers bring taste, experience, and intention to the process. GameGrammar makes the recombination step visible and fast, so you can spend more time on the parts that require your judgment.

What AI genuinely lacks is intention. When you say “I want to create the feeling of surviving in a harsh wilderness,” that vision, that lived experience compressed into a creative direction, is yours alone. The AI has no memories, no desires, no reasons to create this game rather than that one. This is why the process separates your vision (human) from generation (AI) from refinement (collaborative). You provide the “why.” The AI provides the “how.” The design that emerges from working together is genuinely new.

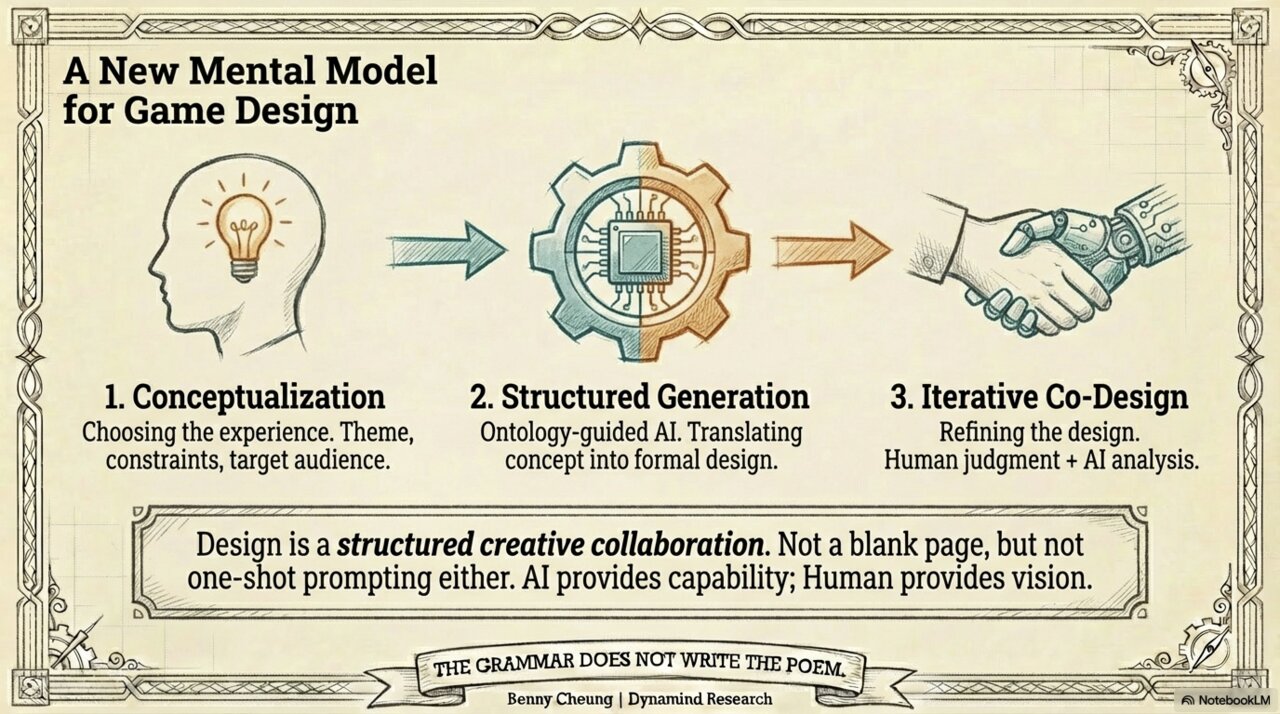

A New Way of Working

Figure. Design as structured creative partnership. Not a blank page, and not one-click magic either.

GameGrammar suggests that game design works best as a three-part activity:

- Your Vision: choosing the experience you want to create, the theme, player count, complexity, who will play it. This is entirely yours.

- AI Generation: translating that vision into a structured first draft, grounded in real game design knowledge. This is where AI does its best work.

- Collaborative Refinement: shaping the generated design through your judgment, assisted by AI analysis. This is where the partnership shines.

This is different from both traditional design (entirely solo, often unstructured, reliant on personal experience) and naive AI generation (typing “make me a board game” and hoping for the best). It positions design as a creative partnership where your vision and AI capability each contribute what they do best.

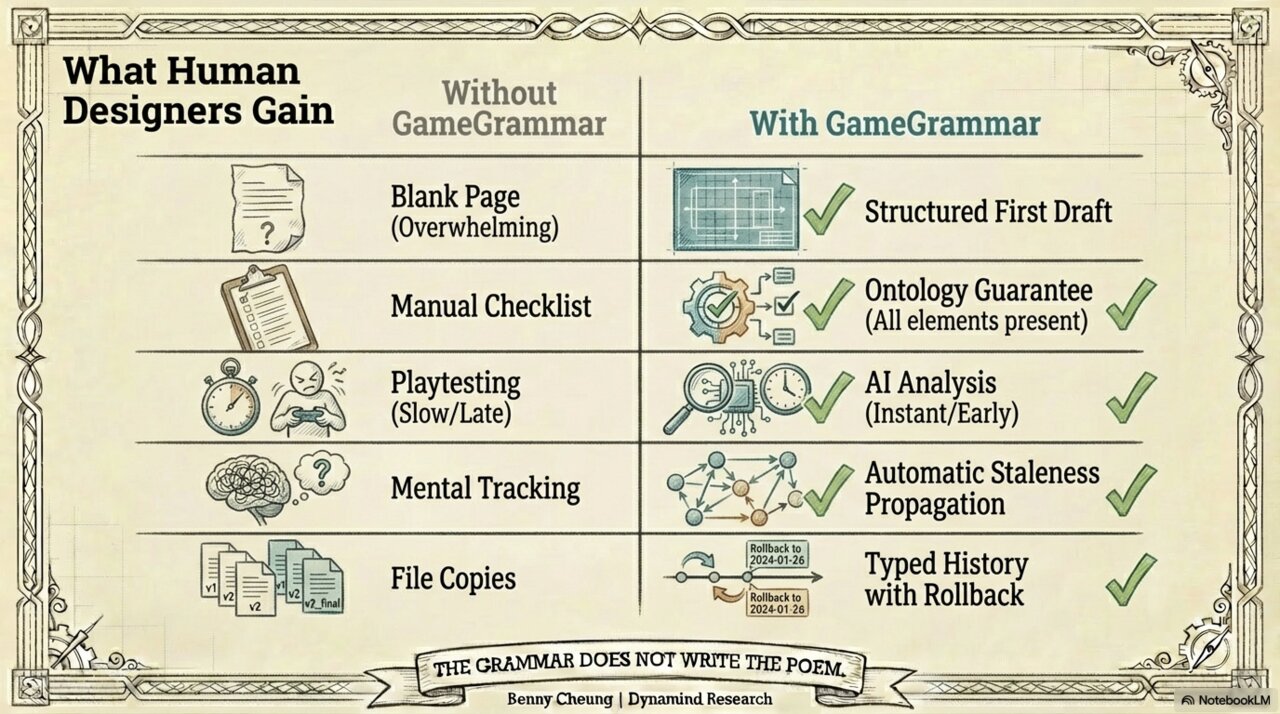

Figure. The blank page becomes a structured first draft. Manual tracking becomes automatic change detection. Gut feeling becomes measurable creative vitality.

| What You Need | Without GameGrammar | With GameGrammar |

|---|---|---|

| Starting a design | Blank page, overwhelming options | Structured first draft from your theme and constraints |

| Making sure nothing is missing | Mental checklist, easy to overlook | Every required element guaranteed present |

| Catching contradictions early | Often surfaces during playtesting | AI flags some issues before you reach the table |

| Updating connected sections | Keeping it all in your head | Automatic change tracking across your design |

| Exploring alternatives | Designing variants by hand | AI suggestions and plain-language editing |

| Measuring quality | “I think it feels good?” | Six scored dimensions, originality percentile, engagement curve |

| Tracking versions | File copies, or nothing at all | Full version history with comparison and rollback |

GameGrammar does not claim that AI can replace you. The theory puts the designer firmly in the author’s chair and the AI in the assistant’s seat. The AI can spot that your cooperative game has contradictory competitive elements. It cannot know whether you put that tension there on purpose. The value is in making the structural side of design faster and more visible, so you can pour your energy into the creative decisions that only a human designer can make.

Concluding Remarks

GameGrammar’s design theory can be stated simply:

Games have shared structure. That structure makes generation possible. But generation is not design. Design is the back-and-forth refinement of a generated starting point, where AI proposes and the designer decides.

No single piece of this is revolutionary on its own. Structured game vocabularies exist. AI generation exists. Iterative design is as old as design itself. The contribution is the synthesis: a unified workbench where structured vocabulary, AI generation, change tracking, consistency checking, proactive suggestions, six-dimensional evaluation, and creative vitality metrics all work together as one coherent system.

The three-layer model keeps your game separate from the process of making it. The preview-before-apply rule keeps you in control. The Creative Coach dashboard answers not “what is broken?” but “what makes this design special?” And the four-stage workbench, from genesis through shaping, refinement, and polish, gives you a natural rhythm for the work.

For the design community, this offers a new way of working: not AI replacing designers, not designers ignoring AI, but a structured partnership where each contributes what they do best. The grammar constrains. The AI creates within those constraints. You decide what the game should be.

The AI handles the mechanics. You bring the meaning. That division of labor is the whole theory in one sentence.

The grammar does not write the poem. But without grammar, there is no poem to write.

GameGrammar is available in public beta at gamegrammar.dynamindresearch.com. Try it. Generate a game from your favorite theme. Study the radar chart. Make some changes and hit Re-Evaluate. Watch the scores move. Then decide for yourself whether this partnership is worth having.

Series

- Unlocking the Secrets of Tabletop Games Ontology (Part 4)

- Introducing GameGrammar: AI-Powered Board Game Design (Part 5)

- » GameGrammar: The Theory of Generative Board Game Design (Part 6)

References

[1] Alfred North Whitehead. Process and Reality. Free Press, 1929/1978.

- The philosophical foundation for how abstract design patterns become concrete games

[2] Benny Cheung. Process Philosophy for AI Agent Design. bennycheung.github.io, Jan 2026.

- A deeper exploration of how process philosophy connects to AI creativity

[3] Geoffrey Engelstein, Isaac Shalev. Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design: An Encyclopedia of Mechanisms. CRC Press, 2022.

- The definitive taxonomy of game mechanisms, and the source for GameGrammar’s mechanism library

[4] Natalya F. Noy, Deborah L. McGuinness. Ontology Development 101. Stanford University.

- How to build structured vocabularies for complex domains

[5] Benny Cheung. Unlocking the Secrets of Tabletop Games Ontology. bennycheung.github.io, Feb 2025.

- Where the structured game vocabulary began, analyzing 2,000+ published games

[6] BoardGameGeek. The largest board game database and community.

- Source for the 2,000+ game reference library used in generation and originality scoring

[7] Dynamind Research. AI consulting and product development studio.

- Creator of GameGrammar

[8] Benny Cheung. Generative Ontology: When Structured Knowledge Learns to Create. arXiv:2602.05636, Feb 2026.

- The formal paper describing GameGrammar’s generative ontology framework, six-agent pipeline, and evaluation methodology