artwork by Gemini 3 Pro (Nano Banana Pro)

FoodInsight: Edge AI Food Monitoring with Local-First Architecture

FoodInsight

Part 2 of 3What’s on the table? It’s a simple question, yet answering it reliably requires walking to the kitchen. FoodInsight changes this by combining edge AI with local-first architecture, transforming a Raspberry Pi and camera into an intelligent food monitoring system. No cloud dependency. No images leaving your network. Just real-time visibility into what food is available, powered by YOLO11 and the UEC FOOD 100 dataset.

Figure. FoodInsight in action: A Raspberry Pi camera monitors a dining table, detecting Japanese dishes in real-time with YOLO11. Each dish receives a bounding box and confidence score, from rice (0.94) to tempura (0.92), all processed locally on edge hardware.

In our previous article, You Only Look Once: 8 Years of Food Detection Evolution, we explored the remarkable journey from YOLO v2 to YOLO11 and trained a food detection model achieving 0.79 mAP50 on the UEC FOOD 100 dataset [1]. That model recognizes 100 categories of Japanese cuisine, from rice and miso soup to tempura and sushi. The article ended with a vision: what happens when you deploy this model beyond the desktop to monitor real food on real tables?

This article answers that question. We take the exact YOLO11 model trained in that previous article and deploy it as FoodInsight [2], a complete edge AI system that monitors food on a table, tracks what appears and disappears, and presents the current inventory through a simple phone app. The entire system costs under $140 in hardware, runs entirely offline, and processes everything locally. No cloud subscriptions. No data leaving your premises. No privacy concerns.

Figure. FoodInsight transforms a Raspberry Pi with camera into an intelligent food monitoring station. Edge AI detects food items using YOLO11, tracks inventory changes with ByteTrack, and serves real-time status through a local PWA.

The Visibility Problem

Every shared kitchen tells the same story. Someone prepares food. Dishes appear on the table or counter. Others don’t know what’s there. They either check repeatedly, ask around, or miss the meal entirely. The result is cold food, wasted effort, and the nagging uncertainty of not knowing what’s available.

This pattern repeats across contexts:

- Home kitchens: Family members don’t know when dinner is ready or what dishes are on the table

- Shared meals: Guests miss dishes at the far end of the table, don’t know what options remain

- Office lunch rooms: Employees walk to the kitchen just to see if the catered lunch has arrived

- Cafeterias and buffets: Diners and staff don’t know which items need restocking until they’re gone

The solution seems obvious: take a photo and share it. But photos are static. They require someone to take them. They become stale within minutes. They don’t tell you when something changed.

What if the monitoring happened automatically, continuously, and privately?

Enter FoodInsight

FoodInsight is our answer to the visibility problem. It’s a three-component system that monitors food in real-time while respecting privacy and operating entirely offline.

The Core Components

| Component | Technology | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Edge Detection | Raspberry Pi + YOLO11n [3] | Detects and tracks food items |

| Local Backend | FastAPI + SQLite | Stores inventory, serves API |

| Consumer PWA | Vue 3 + Vite | Shows current food availability |

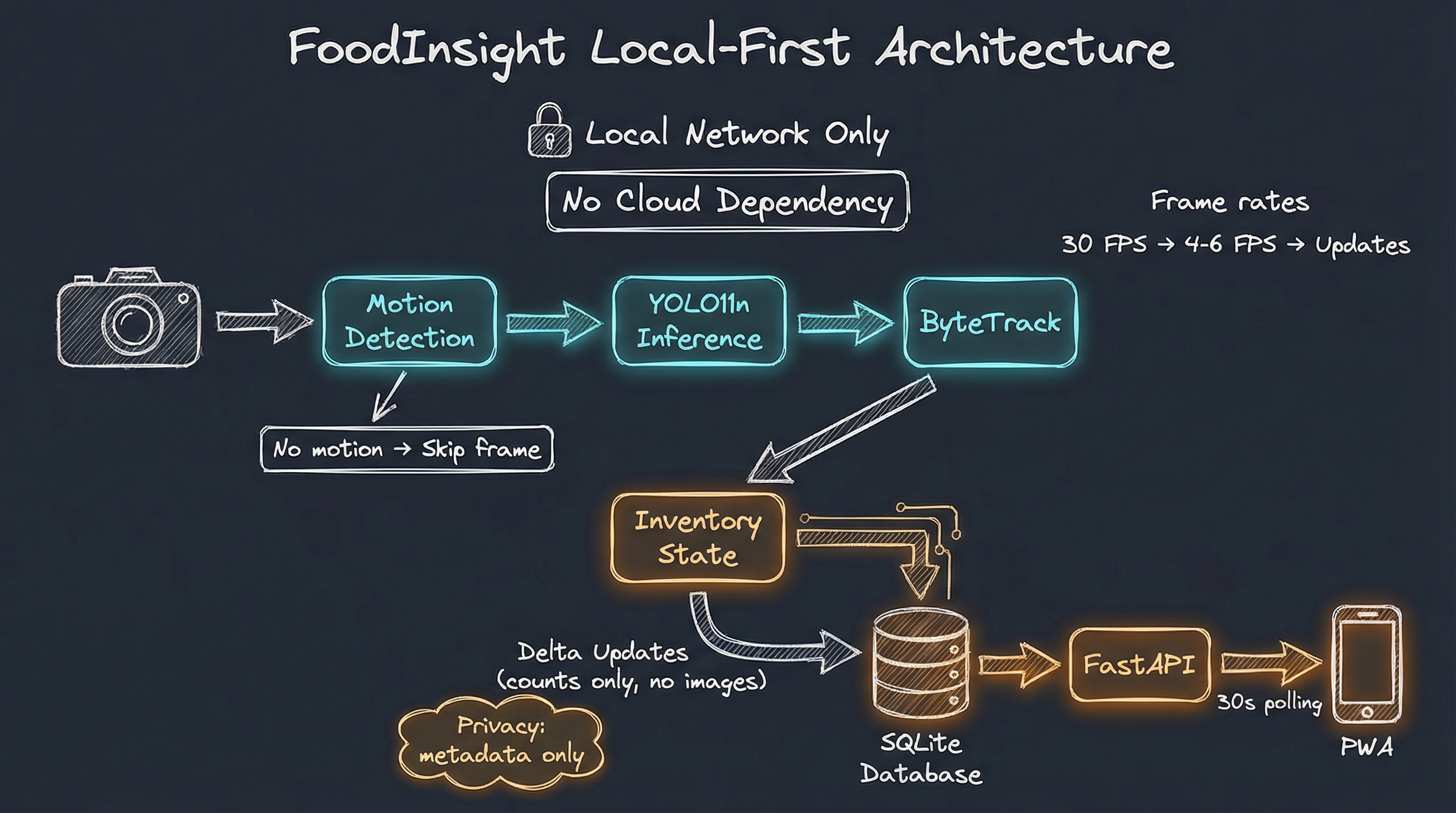

The design philosophy is “local-first” [4]. Every piece of data stays on your network. The edge device processes video frames directly, never storing or transmitting images. Only inventory counts travel to the backend, and even that stays on your local network.

Figure. FoodInsight local-first architecture: Camera frames flow through motion detection and YOLO11n inference on the edge device. Only inventory deltas (counts, not images) push to the local SQLite backend. The PWA polls for updates every 30 seconds.

Why Local-First?

The decision to build FoodInsight as a local-first system wasn’t arbitrary. It emerged from several constraints and principles:

Privacy by Design: Food monitoring cameras in shared spaces raise legitimate privacy concerns. By processing everything locally and never storing images, FoodInsight eliminates the “surveillance” feeling that would make users uncomfortable.

Zero Cloud Cost: Cloud backends incur ongoing costs, whether through compute, storage, or API calls. A local SQLite database costs nothing beyond the initial hardware.

Reliability: Local systems don’t fail when the internet goes down. For something as mundane as checking food availability, reliability matters more than features.

Simplicity: Cloud infrastructure requires configuration, credentials, billing, and ongoing maintenance. Local SQLite requires a single file.

The Edge: Where Detection Happens

The heart of FoodInsight is the edge detection service running on a Raspberry Pi. This is where computer vision transforms camera frames into actionable inventory data.

Hardware Requirements

| Tier | Hardware | Cost | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Budget | Raspberry Pi 4 + Camera Module 3 | ~$110 | 1-3 FPS |

| Standard | Raspberry Pi 5 + Camera Module 3 | ~$139 | 4-6 FPS |

| Development | Mac/Linux with webcam | - | 45+ FPS |

Why CPU-only instead of adding an AI accelerator? The Hailo-8L would boost performance to 15-25 FPS but adds $70 to the hardware cost. For monitoring a relatively static food table, 4-6 FPS is more than sufficient. Motion detection further reduces the average processing load, so the CPU spends most of its time idle. The savings buy simplicity: no accelerator drivers, no thermal management complexity, just straightforward CPU inference.

The development tier runs the same code on a desktop or laptop for testing before deployment. This proved invaluable during development, as we achieved approximately 45 FPS on an M4 Pro Mac, allowing rapid iteration without waiting for the slower Raspberry Pi.

The Detection Pipeline

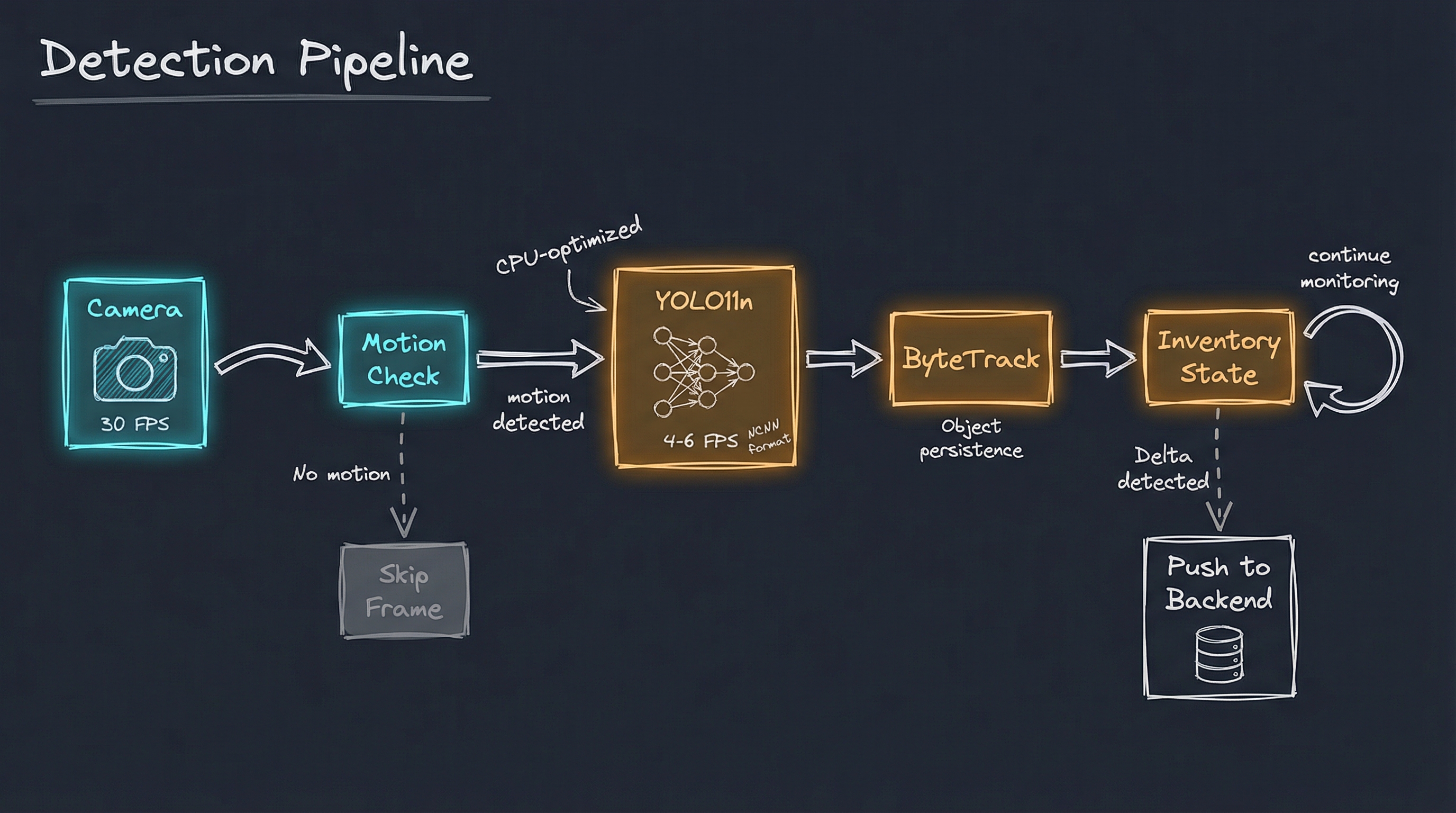

Each camera frame flows through a carefully designed pipeline:

Figure. The FoodInsight detection pipeline: Camera frames at 30 FPS flow through motion detection, which gates expensive YOLO11n inference. Only frames with detected motion proceed to object detection at 4-6 FPS, then ByteTrack for persistence, and finally inventory state management that pushes deltas to the backend.

Motion Detection saves CPU cycles. The camera captures at 30 FPS, but we only run expensive YOLO inference when something changes. A simple frame differencing algorithm with a threshold of 0.008 detects movement. No motion means no inference, reducing CPU load dramatically.

YOLO11n Inference runs in NCNN format [5], optimized for ARM CPUs. The “n” in YOLO11n stands for “nano,” the smallest and fastest variant. On a Raspberry Pi 5, this achieves 4-6 FPS, sufficient for monitoring a relatively static scene like a food table.

ByteTrack [6] maintains object persistence across frames. Without tracking, every frame would report “new” detections. ByteTrack assigns persistent IDs to objects, enabling the system to understand when items are taken (ID disappears) or added (new ID appears).

Inventory State Manager bridges detection and the backend API. It maintains a local count of each food category, compares each frame’s detections against the previous state, and calculates deltas. When counts change, it batches updates (maximum one API call per second) and pushes only the differences to the backend. This reduces network traffic and ensures the backend always reflects the current table state.

Deploying the UEC FOOD 100 Model

FoodInsight deploys the exact model we trained in the previous article. The YOLO11n model weighs just 22MB in NCNN format, small enough to fit comfortably on the Raspberry Pi while recognizing all 100 categories from the UEC FOOD 100 dataset [1]. This includes diverse Japanese dishes:

# config/settings.py - UEC FOOD 100 categories

FOOD_CLASSES = [

"rice", "eels_on_rice", "pilaf", "chicken_and_egg_on_rice",

"pork_cutlet_on_rice", "beef_curry", "sushi", "chicken_rice",

"fried_rice", "tempura_bowl", "bibimbap", "toast", "croissant",

"roll_bread", "raisin_bread", "chip_butty", "hamburger", "pizza",

"sandwiches", "udon_noodle", "tempura_udon", "soba_noodle",

"ramen_noodle", "beef_noodle", "tensin_noodle", "fried_noodle",

"spaghetti", "Japanese_tofu_and_vegetable_chowder", "pork_miso_soup",

"chinese_soup", "beef_bowl", "kinpira_style_sauteed_burdock",

"croquette", "grilled_eggplant", "sauteed_vegetables", "chinjaorosu",

"stew", "oden", "omelet", "ganmodoki", "jiaozi", "stir_fried_pork",

# ... all 100 categories

]

Unlike a generic COCO-pretrained model that detects everything from people to traffic lights, our model focuses exclusively on food. This specialization, combined with the configurable class filter, dramatically reduces false positives from non-food objects in the scene.

Privacy Through ROI Masking

Not every part of the camera frame needs processing. FoodInsight allows administrators to define a Region of Interest (ROI) that restricts detection to specific areas:

Figure. The admin portal allows ROI configuration through a simple drag interface. Only the defined region is processed for food detection. Areas outside the ROI are masked, never analyzed or stored.

This serves multiple purposes:

- Privacy: Exclude areas where people might walk by

- Accuracy: Reduce false positives from background objects

- Performance: Process fewer pixels, faster inference

The admin portal runs on Flask + HTMX [7] rather than extending FastAPI. Why a separate framework? Flask is lighter weight on the resource-constrained edge device, HTMX provides dynamic UI without heavy JavaScript, and MJPEG video streaming is simpler in Flask. The portal is accessible only on the local network, streaming live video with detection overlays, displaying current inventory, and allowing configuration changes.

The Backend: Local Data Storage

The backend serves two purposes: receive inventory updates from the edge device and provide an API for the consumer app. Built with FastAPI [8] and SQLite [9], it embodies the local-first philosophy.

SQLite: The Perfect Local Database

Why SQLite instead of Firebase or another cloud database? For a single-device prototype, cloud sync adds complexity without benefit. SQLite provides everything we need with zero cloud cost, zero configuration, and complete offline operation. The trade-off is no multi-device sync or off-site backup, but neither matters for a kitchen prototype.

SQLite delivers:

- Zero configuration: No server to run, no credentials to manage

- Single file: The entire database lives in

data/foodinsight.db - ACID compliant: Reliable even if power fails mid-write

- Fast: Sub-millisecond queries for our simple data model

The schema captures inventory state and change history:

-- Current inventory state

CREATE TABLE inventory (

id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT,

item_name TEXT NOT NULL UNIQUE,

display_name TEXT,

count INTEGER NOT NULL DEFAULT 0,

confidence REAL DEFAULT 0.0,

last_updated TIMESTAMP DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP

);

-- Detection events log

CREATE TABLE events (

id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT,

event_type TEXT NOT NULL, -- 'FOOD_TAKEN' | 'FOOD_ADDED'

item_name TEXT NOT NULL,

count_before INTEGER NOT NULL,

count_after INTEGER NOT NULL,

timestamp TIMESTAMP DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP

);

API Design

The API follows a simple pattern: public endpoints for reading, authenticated endpoints for administration.

| Endpoint | Method | Auth | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

/inventory |

GET | None | Current food inventory |

/inventory/update |

POST | None | Edge device pushes updates |

/inventory/events |

GET | None | Recent change history |

/admin/status |

GET | Basic | System status |

/admin/config |

PUT | Basic | Update configuration |

The public inventory endpoint intentionally requires no authentication. Anyone on the local network can check what food is available. This eliminates friction and matches the “glanceable” design goal.

Response Format

A typical inventory response reflects the UEC FOOD 100 categories:

{

"device_id": "kitchen-001",

"location": "Dining Table",

"last_updated": "2026-01-12T14:30:00",

"items": [

{"item_name": "rice", "display_name": "Rice", "count": 3, "confidence": 0.94},

{"item_name": "pork_miso_soup", "display_name": "Pork Miso Soup", "count": 2, "confidence": 0.89},

{"item_name": "grilled_salmon", "display_name": "Grilled Salmon", "count": 1, "confidence": 0.91},

{"item_name": "tempura", "display_name": "Tempura", "count": 0, "confidence": 0.0},

{"item_name": "sushi", "display_name": "Sushi", "count": 4, "confidence": 0.87}

]

}

Items with count 0 remain in the response so the app can show “Finished” rather than hiding items entirely. This helps diners know what was available even if they missed it.

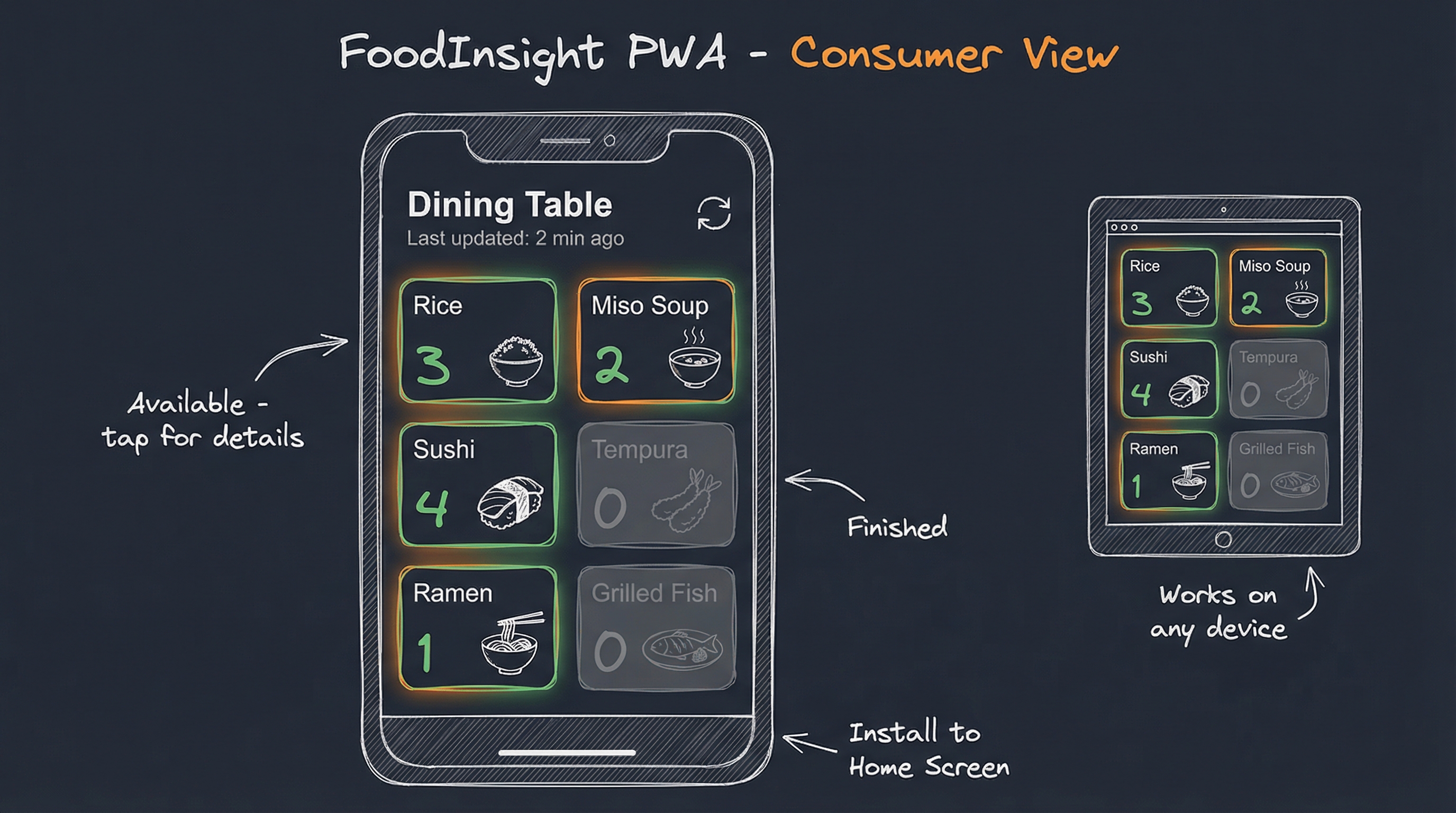

The Consumer Experience: PWA

The final piece is what users actually see: a Progressive Web App that displays current food availability on any device.

Design Principles

| Principle | Implementation |

|---|---|

| Glanceable | Large cards, clear counts, obvious stock status |

| Zero Friction | No login, no signup, just open and view |

| Mobile First | Touch-friendly, works on any screen size |

| Fast | Loads in under 2 seconds, caches aggressively |

| Installable | Add to home screen for native-app feel |

Technology Choices

The PWA uses Vue 3 [10] with the Composition API, Pinia for state management, and Tailwind CSS for styling. Vite [11] handles building and development. The entire bundle compresses to about 33KB gzipped.

// stores/inventory.ts

export const useInventoryStore = defineStore('inventory', {

state: () => ({

items: [] as FoodItem[],

lastUpdated: null as Date | null,

loading: false

}),

actions: {

async fetchInventory() {

this.loading = true

try {

const response = await fetch('/api/inventory')

const data = await response.json()

this.items = data.items.map(item => ({

...item,

inStock: item.count > 0

}))

this.lastUpdated = new Date(data.last_updated)

} finally {

this.loading = false

}

}

}

})

Auto-Refresh

The PWA polls for updates every 30 seconds. This interval balances freshness against battery life on mobile devices. A visible “Last updated” timestamp lets users know how recent the data is.

Why polling instead of WebSocket real-time updates? Polling is simpler to implement and debug, works well with CDN caching, and requires no persistent connection management. The trade-off is that users might see stale data for up to 30 seconds, but for checking food availability, this delay is acceptable. Real-time WebSocket updates are a natural extension for a future phase if the latency proves problematic.

Figure. The FoodInsight PWA displays the current meal status as a grid of cards showing UEC FOOD 100 categories. Green indicates available dishes with counts. Gray indicates finished items. The interface works on phones, tablets, and desktops.

Deployment: From Development to Kitchen

FoodInsight runs in three environments: development on a Mac/Linux desktop, testing on the target Raspberry Pi, and production in the actual kitchen or break room.

Development Mode

For rapid iteration, we run everything on a development machine:

# Terminal 1: Edge detection with live camera

python run_dev.py --config dev_config.json

# Terminal 2: Backend API

cd server && uvicorn app.main:app --port 8000

# Terminal 3: PWA development server

cd app && bun run dev

The dev_config.json file specifies development-friendly settings, pointing to the UEC FOOD 100 trained model:

{

"machine_id": "dev-mac",

"model_path": "models/yolo11n_food100.ncnn",

"camera_index": 0,

"admin_port": 8080,

"api_url": "http://localhost:8000",

"allowed_classes": ["rice", "pork_miso_soup", "sushi", "ramen_noodle",

"tempura", "grilled_salmon", "beef_curry", "udon_noodle"],

"motion_threshold": 0.008

}

The model_path points to the NCNN-exported model from our training in the previous article. The allowed_classes can filter to specific categories you expect to see, or be left empty to detect all 100 food categories.

Production Deployment

On the Raspberry Pi, everything runs as systemd services:

# Install edge detection service

sudo cp systemd/foodinsight-edge.service /etc/systemd/system/

sudo systemctl enable foodinsight-edge

sudo systemctl start foodinsight-edge

# Install backend service

sudo cp systemd/foodinsight-api.service /etc/systemd/system/

sudo systemctl enable foodinsight-api

sudo systemctl start foodinsight-api

The services restart automatically on boot and after failures. Logs flow to journald for debugging:

# Monitor edge detection logs

journalctl -u foodinsight-edge -f

# Monitor API logs

journalctl -u foodinsight-api -f

PWA Hosting Options

The PWA can be served in two ways:

Local hosting keeps everything on-premise:

cd app && bun run build

python -m http.server 3000 -d dist

Cloud hosting via Cloudflare Pages enables access from anywhere while the backend stays local:

cd app && bun run build

wrangler pages deploy dist --project-name=foodinsight

With cloud hosting, the PWA loads from the CDN but API calls still go to your local backend. Users need VPN or local network access to see actual data.

Performance and Results

After deployment, FoodInsight meets all the goals defined in the PRD [2]:

| Goal | Target | Achieved |

|---|---|---|

| Model accuracy (mAP50) | ≥75% | 79% (from training) |

| Detection latency | <500ms per frame | 170-250ms |

| API response time | <200ms | <50ms (SQLite is fast) |

| PWA load time | <2 seconds | ~1.5 seconds |

| Hardware cost | <$140 | $139 (Raspberry Pi 5 tier) |

| Cloud cost | $0/month | $0/month |

| Privacy | No images stored | Metadata only |

The 0.79 mAP50 achieved during training translates well to real-world deployment. The model reliably detects common Japanese dishes like rice, miso soup, tempura, and sushi. Performance degrades gracefully for less common categories or unusual presentations, but the system’s value lies in visibility, not perfect accuracy. Knowing “there’s probably sushi on the table” is far more useful than not knowing at all.

The system tracks when items appear or disappear and updates the PWA within the 30-second polling interval. In practice, the detection latency of 170-250ms means inventory updates reach the backend within seconds of a dish being placed or removed.

Lessons Learned

Building FoodInsight taught us several lessons about edge AI deployment:

1. Motion detection is essential. Without it, the Raspberry Pi CPU would be saturated running YOLO inference at camera frame rate. Motion detection reduces load to near-zero when nothing changes.

2. Model export format matters. NCNN format runs significantly faster than ONNX on ARM CPUs. The export step (yolo export format=ncnn) is trivial but critical for edge performance.

3. ByteTrack needs tuning. The default tracker configuration caused ID flickering. Adding fuse_score: true to the tracker config stabilized object persistence.

4. SQLite is underrated. We initially considered Firebase for “real” persistence. SQLite proved simpler, faster, and more reliable for single-device use.

5. PWA beats native apps. Building native iOS and Android apps would require separate codebases, app store approval, and ongoing maintenance. The PWA works everywhere with a single codebase.

Future Directions

FoodInsight as built solves the visibility problem. Several extensions could make it more valuable:

Nutrition Tracking: Connect detected foods to a nutrition database. Estimate portion sizes. Log meals automatically to health apps.

Expiration Awareness: Track when items appear and alert when they’ve been sitting too long. Reduce food waste by surfacing “use soon” items.

Multi-Device Sync: Replace SQLite with a sync-capable database like LiteFS or CRDTs. Enable multiple kitchen stations feeding a single dashboard.

WebSocket Real-Time: Eliminate polling delay with WebSocket connections. Show inventory changes as they happen.

Custom Model Training: Train on photos from the actual deployment environment. Improve accuracy for specific food items that appear frequently.

Concluding Remarks

FoodInsight demonstrates that practical edge AI is within reach for anyone with basic development skills and modest hardware. The combination of YOLO11, Raspberry Pi, and local-first architecture creates a system that was impossible to build affordably just a few years ago.

This project completes a journey that began in 2018 [12] when we first trained YOLO v2 on the UEC FOOD 100 dataset. Eight years later, the same dataset powers a complete edge AI system that runs on a $139 device. The model is smaller, faster, and more accurate. The deployment is simpler. The result is more useful.

The key insight is that useful AI doesn’t require cloud scale. A $139 edge device running a 22MB model can solve real problems that matter in daily life. No subscriptions. No data leaving your premises. No privacy concerns.

We started with a simple question: “What’s on the table?” Building the answer required computer vision, object tracking, API design, and web development. But the result is elegantly simple: point a camera at the food, check your phone, know what’s available.

The code is open source at github.com/bennycheung/FoodInsight [2]. Build your own. Adapt it for your kitchen, dining room, or office lunch area. The visibility problem is universal. Now the solution is too.

References

[1] Matsuda, Y., Hoashi, H., and Yanai, K. Recognition of Multiple-Food Images by Detecting Candidate Regions. IEEE ICME, 2012.

- The UEC FOOD 100 dataset from the University of Electro-Communications, containing 14,361 images across 100 Japanese food categories.

[2] Benny Cheung. FoodInsight Project. GitHub, 2026.

- The complete FoodInsight source code including edge detection, backend API, and consumer PWA.

[3] Ultralytics. YOLO11 Documentation. Ultralytics, 2024.

- Comprehensive documentation for YOLO11 object detection, including model variants, training, and deployment options.

[4] Kleppmann, M., Wiggins, A., van Hardenberg, P., and McGranaghan, M. Local-First Software. Ink & Switch, 2019.

- Foundational article on local-first software principles: data ownership, offline capability, and privacy by default.

[5] Tencent. NCNN: High-Performance Neural Network Inference Framework. GitHub, 2017.

- Optimized neural network inference for mobile and embedded platforms, enabling efficient CPU-based inference on ARM devices.

[6] Zhang, Y., Sun, P., Jiang, Y., et al. ByteTrack: Multi-Object Tracking by Associating Every Detection Box. ECCV, 2022.

- High-performance multi-object tracking that associates detection boxes across frames, enabling persistent object identification.

[7] Big Sky Software. HTMX. HTMX.org, 2020.

- Library that allows access to AJAX, CSS Transitions, WebSockets, and Server-Sent Events directly in HTML attributes.

[8] Ramirez, S. FastAPI. FastAPI, 2018.

- Modern Python web framework for building APIs with automatic OpenAPI documentation and Pydantic validation.

[9] SQLite Consortium. SQLite. SQLite.org, 2000.

- Self-contained, serverless SQL database engine used in billions of devices worldwide.

[10] Vue.js. Vue 3 Documentation. Vue.js, 2020.

- Progressive JavaScript framework for building user interfaces, featuring the Composition API for better code organization.

[11] Vite. Vite Documentation. Vite, 2020.

- Next-generation frontend build tool offering lightning-fast development server and optimized production builds.

[12] Benny Cheung. YOLO for Real-Time Food Detection. Benny’s Mind Hack, 2018.

- The original blog post documenting food detection using YOLO v2 and Darknet, where the food detection journey began eight years ago.

Food Detection Series:

- YOLO for Real-Time Food Detection (2018 - Where it began)

- You Only Look Once: 8 Years of Food Detection Evolution (Training the model)

- » FoodInsight: Edge AI Food Monitoring with Local-First Architecture (Deploying the system)