artwork by Gemini 3 Pro

Generative Ontology: From Game Knowledge to Game Creation

Game Architecture

Part 8 of 7In February 2025, we explored how ontologies reveal the hidden structure of tabletop games. But understanding games is not the same as creating them. What if that same structured knowledge could become a creative engine? This is the promise of Generative Ontology, when knowledge representation learns to imagine.

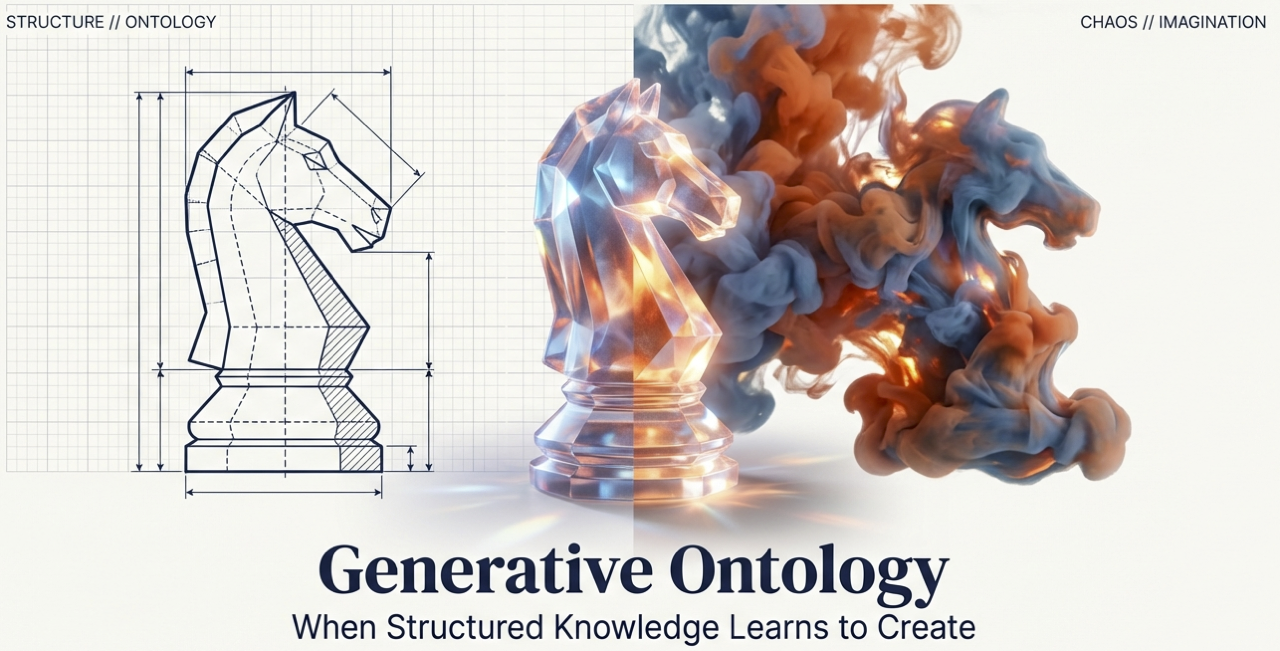

Figure. Structure meets Imagination, the duality at the heart of Generative Ontology.

This article is the conclusion of the Game Architecture series. In Part 4 [8], we built an ontology for tabletop games, decomposing CATAN into mechanisms (resource trading, modular board, dice-driven production), components (hex tiles, resource cards, settlements), and player dynamics (competitive, negotiation-heavy, variable player count). The ontology gave us a vocabulary for understanding games, a precise language for analysis. In Part 5, we demonstrated how that ontology powers a multi-agent generation pipeline. In Part 6, we explored the theory behind structured creative generation. And in Part 7, we showed how a conversational AI partner can learn a designer’s taste.

Figure. Games like CATAN and Dune: Imperium share a common ontological structure beneath their vastly different themes.

Now, in this final article, we tackle the question that analysis alone cannot answer: can the same ontology that helps us understand CATAN help us create games that CATAN’s designers never imagined?

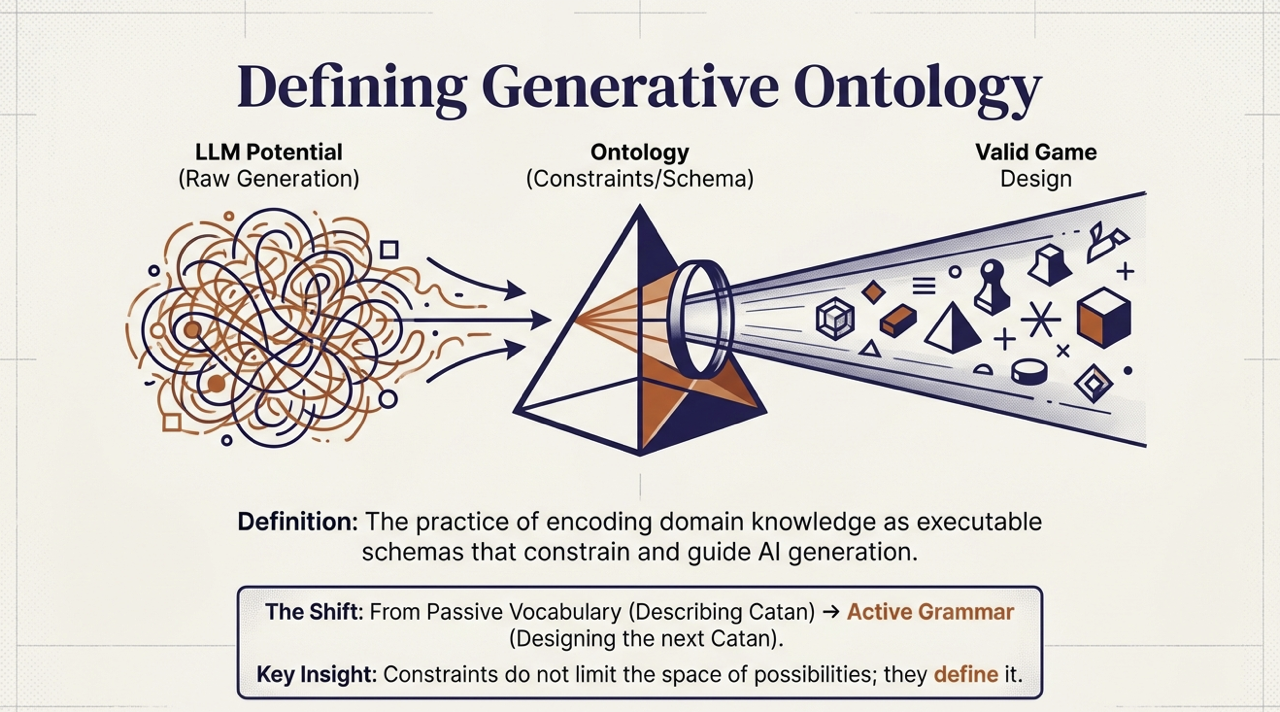

We call this synthesis Generative Ontology: the practice of encoding domain knowledge as executable schemas that constrain and guide AI generation, transforming static knowledge representation into a creative engine. This article presents the theoretical framework, walks through a complete game generation from theme to playable design, and provides the experimental evidence that it works.

From Description to Creation

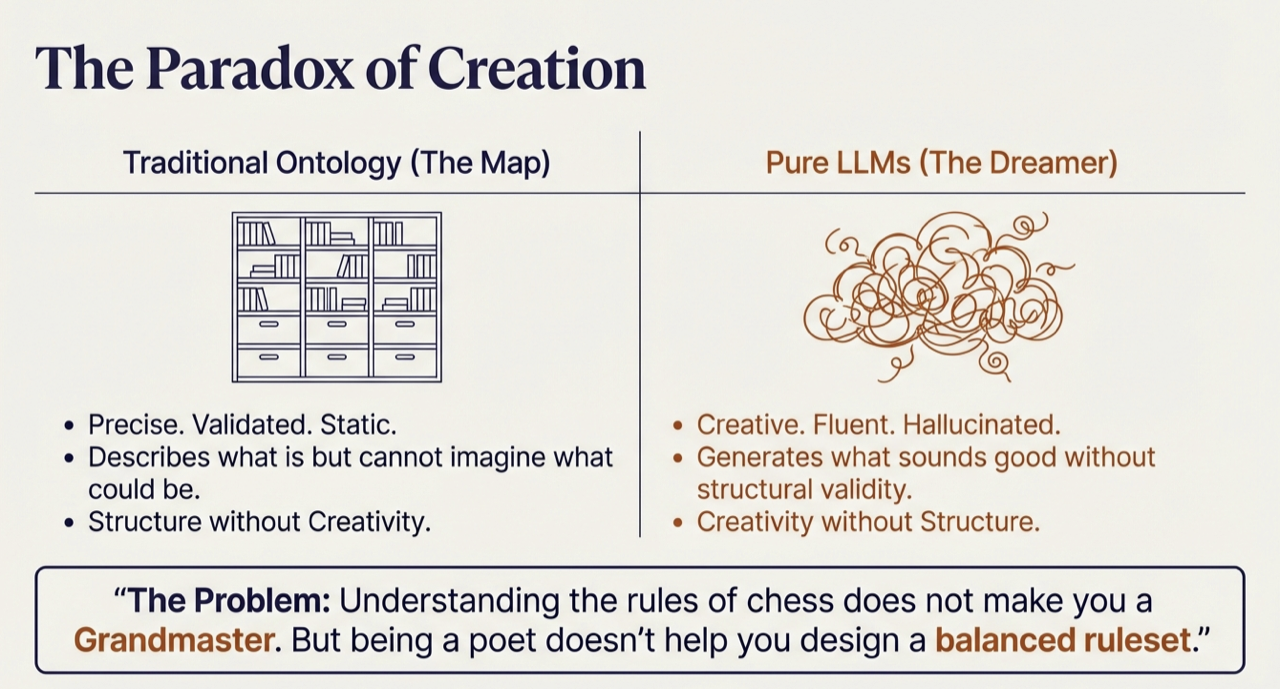

Our game ontology [4] can tell us that worker placement games typically include action spaces, worker tokens, and blocking mechanisms [3]. It cannot generate a novel worker placement game. Large language models have the opposite problem [6]. Ask an LLM to “design a deck-building game set in a haunted mansion,” and it will fluently describe players exploring Ravenshollow Manor, collecting ghost cards, managing a “fear mechanic.” It sounds plausible. But what cards exist in the starting deck? How do players acquire new cards? What triggers the end of the game? The LLM has generated the appearance of a game design without the substance.

Figure. Traditional Ontology (The Map) vs Pure LLMs (The Dreamer), understanding the rules of chess does not make you a Grandmaster.

| Approach | Strength | Weakness |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Ontology | Precise, structured, validated | Cannot generate novel outputs |

| Pure LLM Generation | Creative, fluent, abundant | Unstructured, invalid, hallucinated |

These limitations are complementary [5]. What ontology lacks, LLMs provide. What LLMs lack, ontology provides.

Figure. LLM Potential + Ontology Constraints = Valid Game Design, from passive vocabulary to active grammar.

The Grammar of Games

A poet does not experience grammar as a limitation. Grammar is not what prevents poetry. It is what makes poetry possible. Without syntax, semantics, and form, there would be no sonnets, no haiku, no free verse pushing against convention.

The same principle applies to game design. When we encode our game ontology as a schema, we are not limiting the AI’s creativity. We are giving it the structural vocabulary to be creative coherently. The schema says: every game must have a goal, an end condition, mechanisms that create player choices, components that instantiate those mechanisms. Within those constraints, infinite games are possible. Without them, no valid game emerges.

The grammar does not write the poem. But without grammar, there is no poem to write.

The Whiteheadian Connection

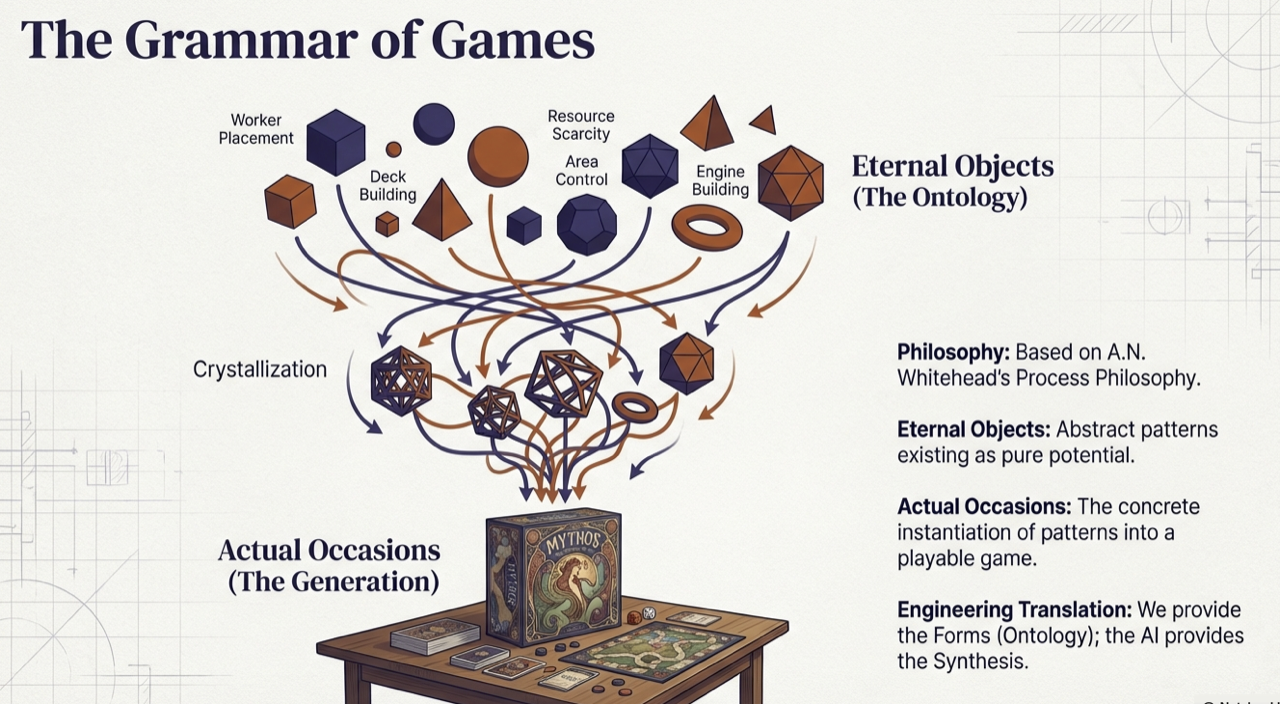

Figure. Eternal Objects (The Ontology) crystallize into Actual Occasions (The Generation), Whitehead’s process philosophy made computational.

In Part 6 and our earlier exploration of Process Philosophy for AI Agent Design [9], we connected Whitehead’s metaphysics to structured generation. Whitehead distinguished between eternal objects (pure forms existing as potentials) and actual occasions (concrete events where forms find expression) [1]. Our game ontology is a collection of eternal objects: the abstract patterns of worker placement, deck building, area control.

What makes this precise is Whitehead’s concept of concrescence: the process by which an actual occasion selects from available eternal objects and synthesizes them into a novel unity [2]. This is exactly what the generation pipeline does. The ontology presents the full space of available patterns. The LLM, constrained by the schema, performs concrescence: selecting from those patterns, combining them with theme, and producing a concrete game that has never existed before. The creativity is real, but it is structured creativity.

From Ontology Classes to Generation Schemas

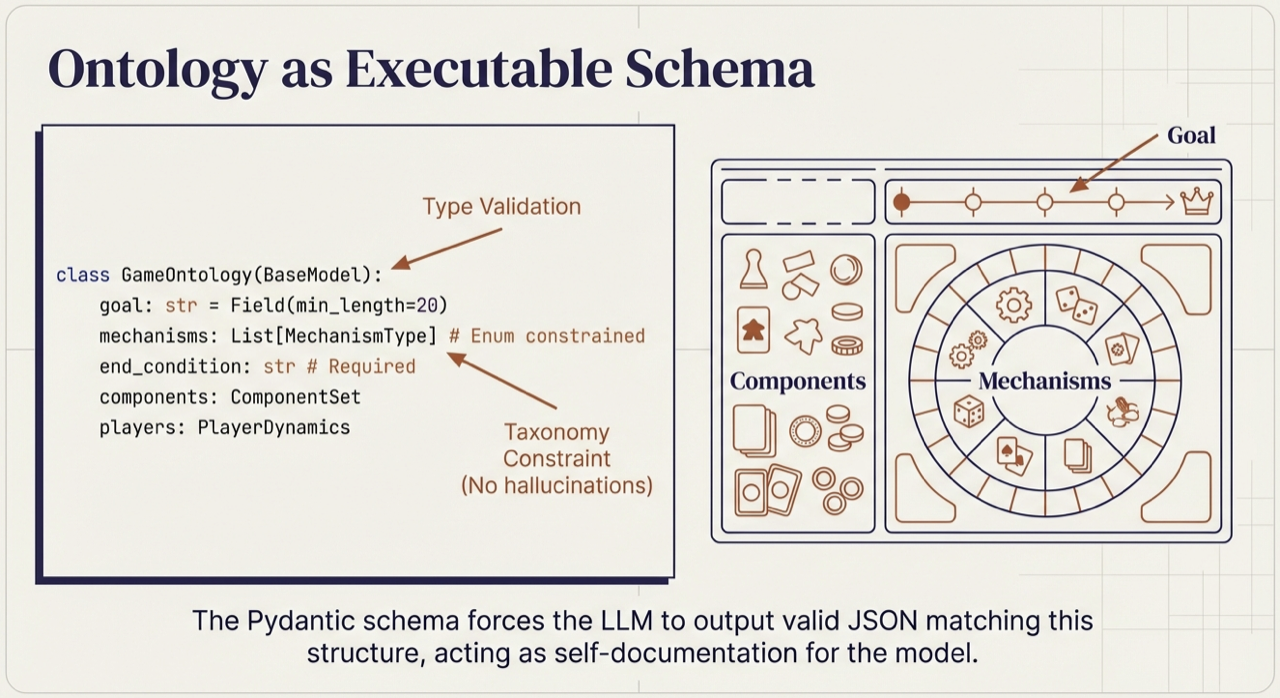

Figure. The schema forces the LLM to output valid structured data matching ontological requirements, acting as self-documentation for the model.

Philosophy illuminates the path; engineering builds the road. The key insight is surprisingly direct: ontology classes map naturally to schema definitions, and schema definitions become the structured outputs that constrain LLM generation.

The Transformation Pipeline

The four ontology concepts from Part 4 [8] — Game, Mechanism, Component, Player — each become typed schema definitions:

| Ontology Concept | Schema Role | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Game Types | Constrained enumeration | Limits to valid game modes (cooperative, competitive, semi-cooperative) |

| Mechanisms | Typed list from taxonomy | Ensures only recognized mechanics are referenced |

| Components | Structured nested object | Specifies physical game elements with required fields |

| Goal and End Condition | Required string fields with minimum length | Guarantees playability criteria are never left vague |

Every ontology class finds expression in the schema. Every relationship (Game has Mechanisms, Game uses Components) becomes a nested structure. The schema is the ontology made executable.

From Static to Generative

The schema flips the ontology’s relationship to creativity. Where ontology was a tool for analysis (decomposing CATAN into its parts), the schema makes it a tool for synthesis. Provide a theme, and the constrained generation produces a complete game satisfying every ontological requirement. The schema does not tell the LLM what game to create. It tells the LLM what a game must be to count as valid.

But a schema alone is not enough. A single LLM call, even constrained by our ontology, must simultaneously consider mechanisms, theme, components, balance, and player experience. Human design teams do not work this way.

Specialized Agents for Each Ontology Domain

Figure. We split the task to create creative tension, preventing shallow, agreeable outputs.

A game designer sketches mechanics while an artist develops visual language while a playtester identifies broken interactions. Each specialist brings focused expertise.

Generative Ontology enables the same division of labor. As we demonstrated in Part 5, we decompose the ontology into domains and assign specialized agents to each. The result is not just better output. It is output that benefits from focused attention at every layer.

The Agent Roster

Our ontology naturally suggests specialization boundaries:

| Agent | Ontology Domain | Expertise | Anxiety |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanics Architect | Mechanisms | Turn structure, action economy, resolution systems | “Is there meaningful player agency?” |

| Theme Weaver | Narrative | Setting, flavor, thematic integration | “Does the theme feel alive in every mechanism?” |

| Component Designer | Components | Cards, tokens, board layout, physical affordances | “Can players physically manipulate this smoothly?” |

| Balance Critic | Cross-domain | Interaction analysis, dominant strategy detection | “What breaks? What is unfun when optimized?” |

| Fun Factor Judge | Player experience | Engagement loops, tension, satisfaction | “Would I want to play this again?” |

The “Anxiety” column is the key design innovation. Each agent is not merely assigned a domain. It is given a concern, a professional worry that shapes its generation and critique. The Mechanics Architect does not just produce mechanisms; it worries about whether those mechanisms create meaningful choices. This anxiety-driven design prevents the “yes-man” tendency of LLMs to produce plausible but shallow output.

The agents have different anxieties: the Mechanics Architect wants elegant systems; the Fun Factor Judge wants excitement. This built-in tension mirrors real design team dynamics. Information flows through the typed schemas as explicit handoffs, and critics identify issues that refiners must address before the pipeline accepts output.

But collaboration alone does not guarantee correctness. Agents can still agree on outputs that look valid but are not. We need a final layer of assurance.

Validation and Refinement: Ontology as Contract

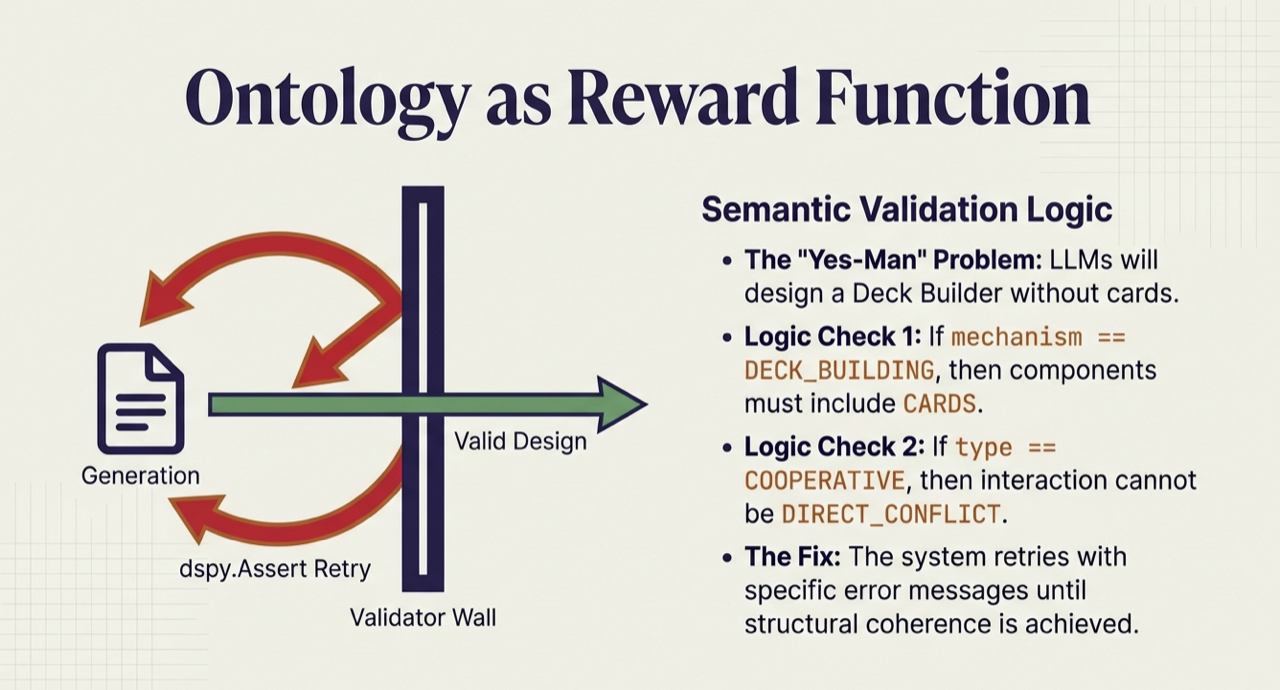

Figure. The system retries with specific error messages until structural coherence is achieved.

Generation is not enough. LLMs are notoriously agreeable. They will produce output that looks valid without ensuring it is valid. The ontology serves not only as a generation schema but as a validation function: a set of constraints that generated designs must satisfy to count as coherent.

Beyond Schema Validation

Schema validation catches type errors and missing fields. But semantic coherence, the relationship between mechanisms and components, between game type and player interaction, requires deeper validation. An LLM might declare “deck building” as a mechanism but include no cards in the components. It sounds valid but is structurally incoherent.

Ontology as Constraint Checker

We encode ontological constraints as validation rules that check cross-field consistency:

- Mechanism-Component Coherence: Deck building requires cards. Area control requires a board. Worker placement requires worker tokens. If a mechanism is declared, the corresponding components must exist.

- Game Type Consistency: Cooperative games cannot have direct conflict as their primary interaction mode. Competitive games should not declare cooperative interaction.

- Playability Requirements: Goals must be specific (not just “win” or “score points”). End conditions must be defined. Turn structure must be specified. Uncertainty sources must exist for replayability.

The Refinement Loop

When validation fails, the system does not simply report an error. It retries generation with the specific constraint violations included as feedback. The LLM sees: “Your previous design violated these constraints: deck-building mechanism declared but no cards in components. Please correct this.”

For complex validation that benefits from multiple attempts, we implement iterative refinement. Generate, validate, identify issues, refine, validate again. This loop continues until the design passes all ontological constraints or a maximum number of attempts is reached.

Validation as Contract

This validation architecture treats the ontology as a contract between the generation system and the downstream consumer. Just as a function signature guarantees what types are returned, the ontology validation guarantees what structure and coherence properties the generated design will have.

Downstream consumers, whether human designers reviewing output, automated balancing tools, or game engines that need to instantiate the design, can rely on these guarantees. The ontology is no longer just a vocabulary for describing games. It is an executable specification that enforces domain validity at generation time.

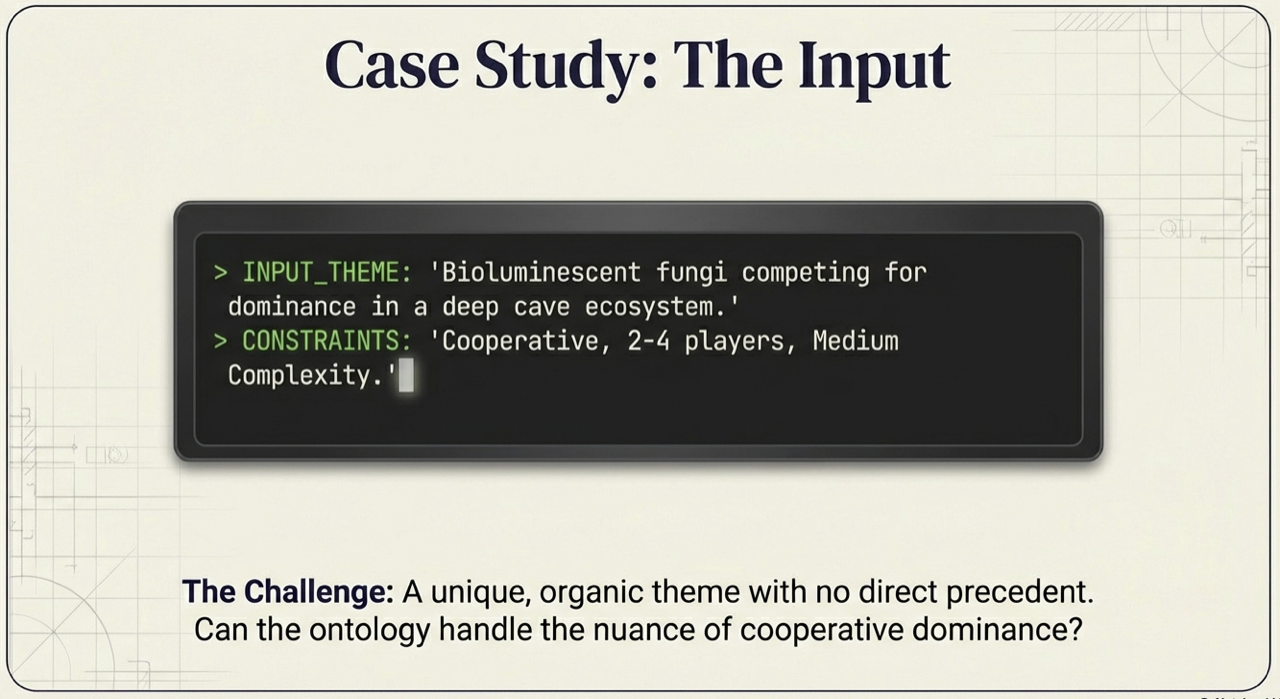

Case Study: A Game of Racing to AGI (Artificial General Intelligence)

Figure. A timely, high-stakes theme with no direct tabletop analog, can the ontology handle the nuance of competitive strategy with hidden information?

How about a game of AGI? Theory is persuasive; demonstration is convincing. Let us trace a complete generation through our Generative Ontology pipeline, from initial theme to playable game design.

The Input

We provide a theme and constraints:

- Theme: “Rival AI laboratories racing to develop Artificial General Intelligence”

- Constraints: 2-4 players, medium complexity, competitive, 45-60 minutes

This theme was chosen deliberately: it is timely enough to resonate but has no direct tabletop analog, forcing the system to synthesize rather than imitate.

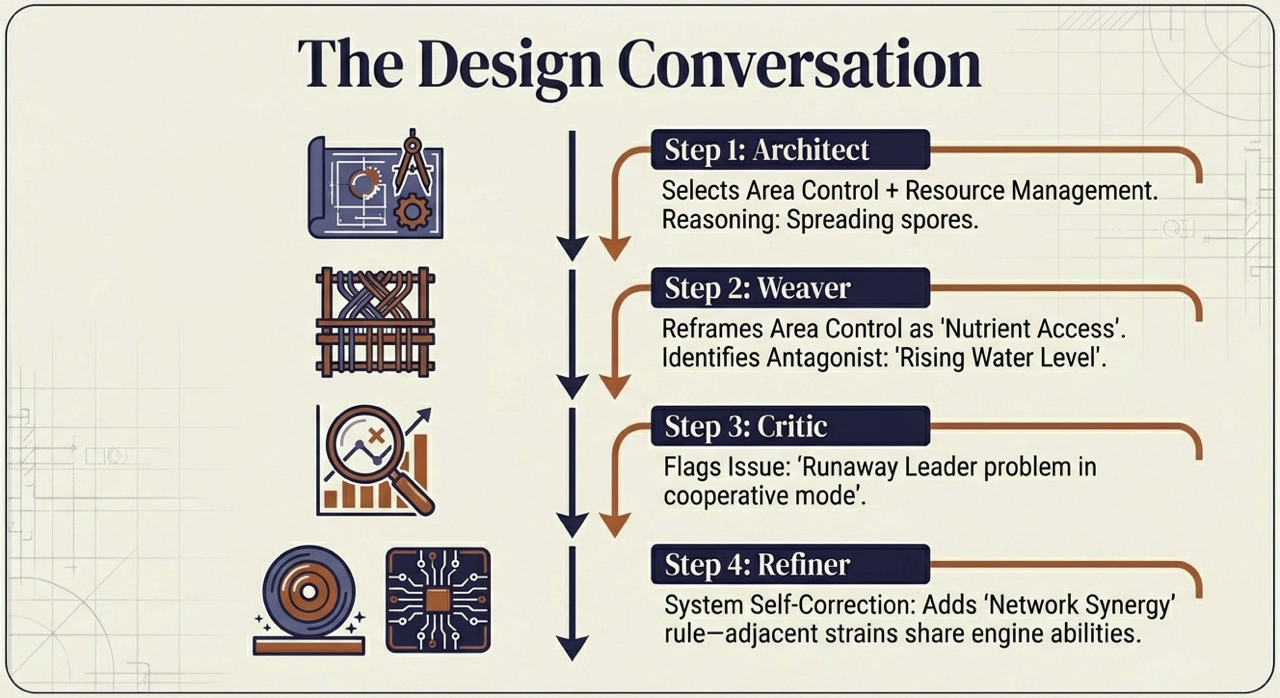

The Design Conversation

Figure. Step-by-step: Architect to Weaver to Critic to Refiner, system self-correction through specialized agents.

The Mechanics Architect analyzes the theme and identifies that rival AI laboratories suggest parallel development, resource competition, and technological breakthroughs. “Racing to AGI” implies a progress track with a finish line. Given the competitive constraint, players race independently toward a shared victory threshold. It selects action point allocation (secret departmental budgeting), engine building (infrastructure and research synergies), market/auction (competitive talent acquisition), and hidden information (unpublished breakthroughs) as core mechanisms. The turn structure combines simultaneous secret planning with sequential resolution.

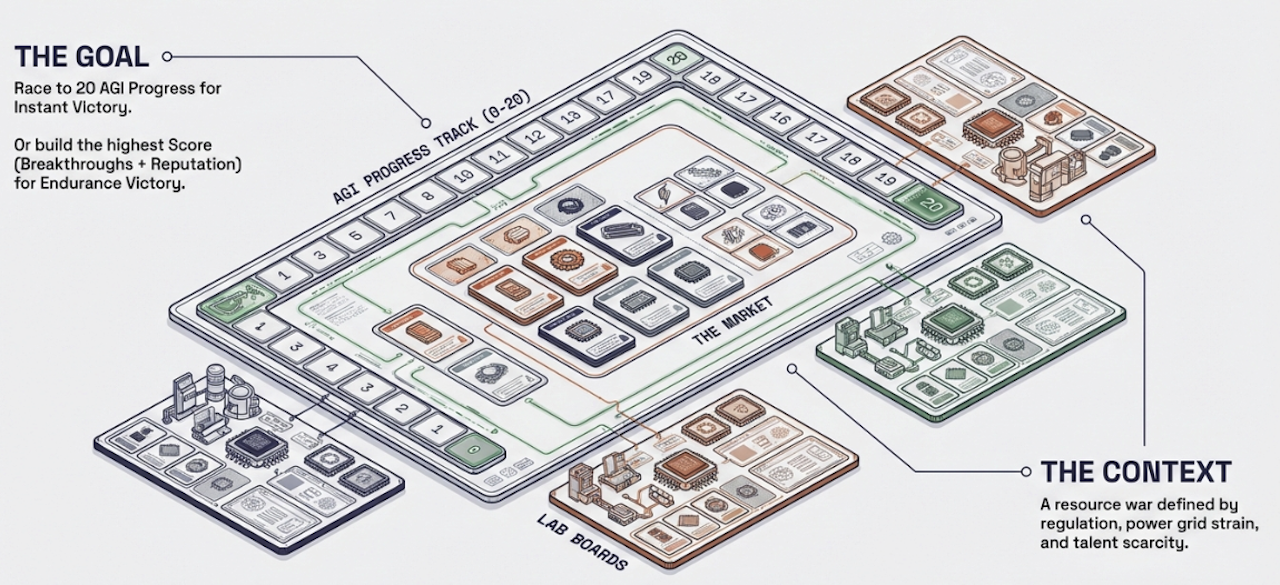

Figure. An imagined board layout for Neural Race – AGI Progress Track, lab boards, talent market, and research breakthrough cards.

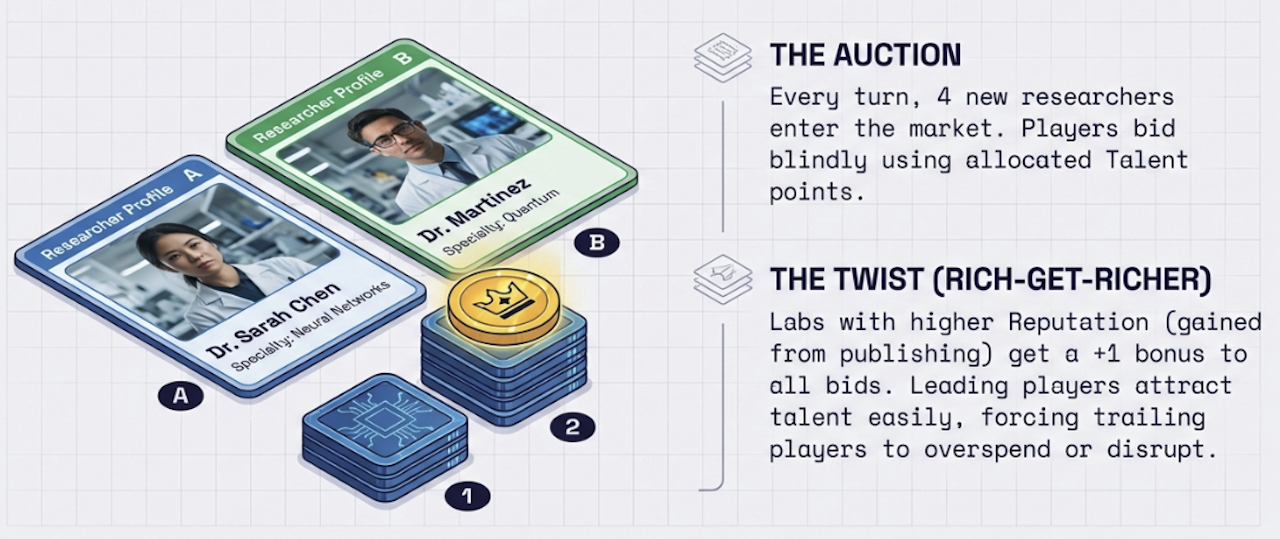

The Theme Weaver receives these mechanics and integrates narrative. Action point allocation becomes lab budget decisions across Research, Talent, Infrastructure, and Intelligence departments. Hidden information becomes proprietary research breakthroughs held secret until strategically published. The market becomes a talent war where labs bid for top AI researchers.

Figure. The talent market auction – researcher cards compete for top specialists, with reputation bonuses creating a rich-get-richer dynamic.

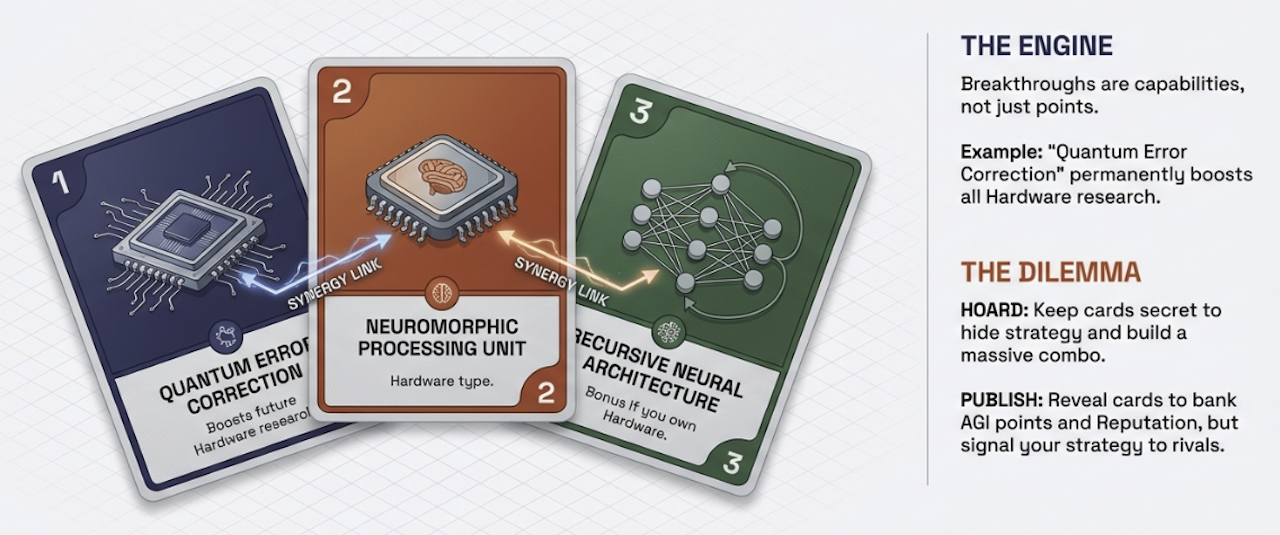

Engine building becomes the pursuit of synergistic breakthroughs across five research fields: Neural Networks, Robotics, Quantum Computing, Ethics & Safety, and Hardware.

Figure. Research breakthrough cards with synergy links – hoard for a massive combo or publish for immediate AGI points and reputation.

External events represent global volatility – regulatory crackdowns, power outages, breakthrough discoveries – that disrupt all players.

Figure. External event cards introduce global disruptions – AI ethics regulation, power grid strain, and breakthrough discoveries that affect all players.

The title emerges: Neural Race.

The Component Designer specifies the physical instantiation: a game board with AGI Progress Track (0-20) and Reputation Track, a 60-card Research Breakthrough deck across five fields, a 32-card Researcher specialist deck, a 24-card External Event deck, Action Point tokens, Reputation markers, and custom wooden robot meeples. Each player gets an allocation mat for secret departmental budgeting.

Figure. An imagined physical component design for Neural Race: 26x30 inch folding board, 116 cards across three decks, 76 tokens, and four custom wooden robot meeples.

The Critic’s Eye

The Balance Critic identifies three issues. First, runaway leader via infrastructure: flat upgrade costs allow leading players to rapidly scale Action Points, creating an insurmountable advantage. Recommendation: cap maximum Action Points at 10 or implement exponentially increasing upgrade costs (3, 5, 8 points). Second, a “rich-get-richer” dynamic in the talent market: reputation bonuses in bidding allow leading labs to acquire the best researchers, cementing their lead. Recommendation: grant bidding bonuses to trailing players or introduce researchers specifically valuable to weaker positions. Third, surprise scoring swings from holding and mass-publishing synergistic breakthroughs. Recommendation: implement stricter hand size limits or mechanics that force partial information reveals.

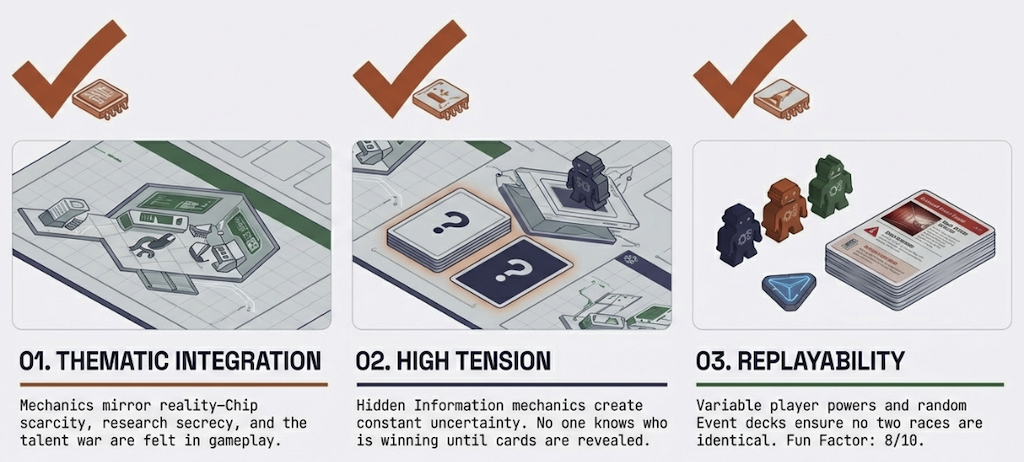

Figure. Design validation – thematic integration, high tension from hidden information, and replayability through variable powers and event decks. Fun Factor: 8/10.

The refinement agent addresses all moderate-severity issues, and the Fun Factor Judge evaluates the refined design at 8/10. Key engagement hooks: the race dynamic as players approach the AGI victory threshold, the uncertainty of opponents’ hidden breakthrough cards, and the risk/reward calculation of when to publish. Tension moments come from the simultaneous secret allocation forcing players to anticipate rivals, the competitive talent market bidding, and the constant pressure of resource scarcity demanding difficult trade-offs.

The Final Design

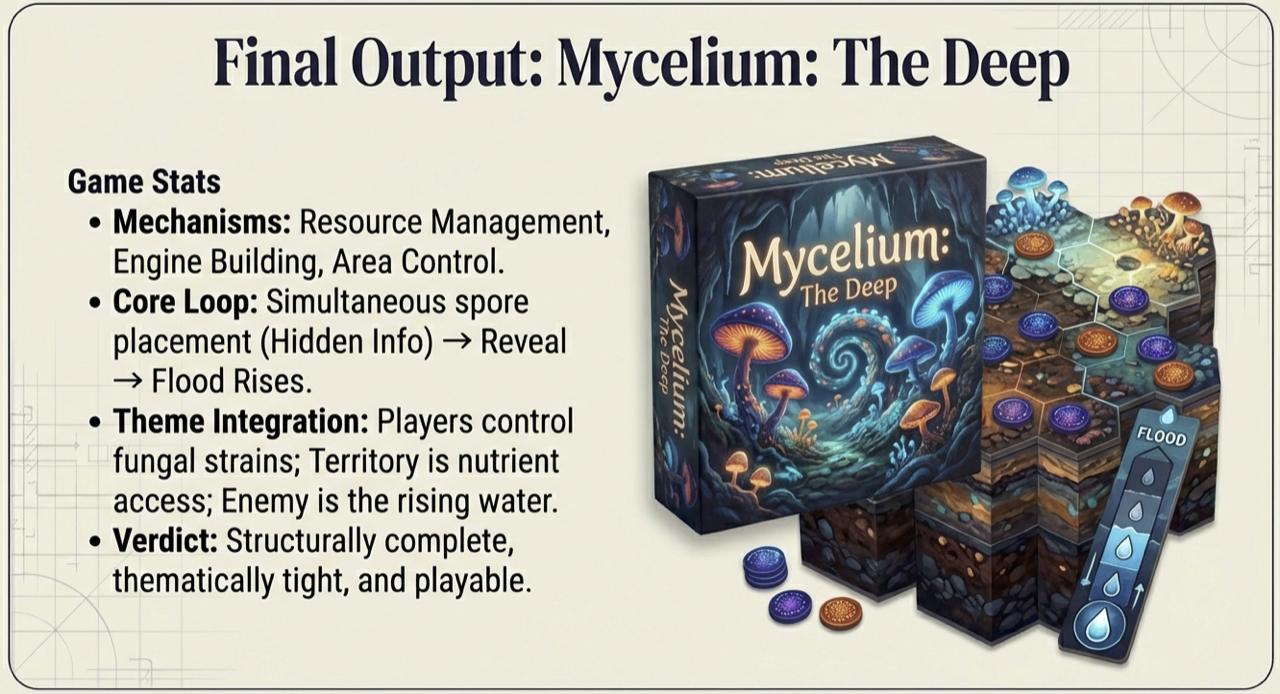

Figure. The AI-generated game design: structurally complete, thematically tight, and ready for prototyping. This is not a published game but a complete design produced entirely by the Generative Ontology pipeline. Explore the complete ontology for Neural Race on GameGrammar [11].

The complete output:

| Field | Value |

|---|---|

| Title | Neural Race |

| Theme | Rival AI laboratories racing to develop AGI in a high-stakes global competition |

| Game Type | Competitive |

| Goal | Advance on the AGI Progress Track by publishing research breakthroughs; first to 20 progress points wins |

| End Condition | Sprint: First player to 20+ AGI progress triggers immediate victory. Endurance: If no player reaches threshold, highest total of AGI progress + synergy bonuses + reputation wins. |

| Mechanisms | Action Point Allocation, Engine Building, Market/Auction, Hidden Information |

| Turn Structure | 1) Secret allocation of Action Points to departments, 2) Research execution and breakthrough draws, 3) Talent market bidding, 4) External event, 5) Progress evaluation |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Interactions | Competitive bidding, hidden breakthroughs, reputation race, variable lab specializations |

| Core Loop | Plan (allocate), Research (draw), Market (bid), Event (adapt), Evaluate (score), Repeat |

Every mechanism maps to a thematic action. Every component serves a mechanical purpose. The full component specification, from the 60-card Research Breakthrough deck to the custom wooden robot meeples, is detailed in the interactive ontology on GameGrammar [11].

What Generative Ontology Provided

Without the ontology schema, an LLM generating “a competitive game about rival AI labs” would likely produce vague victory conditions (“be the first to develop AGI somehow”), inconsistent mechanisms (mentioning an auction but specifying no bidding currency), missing components (no actual game pieces defined), and disconnected theme (mechanics unrelated to research or competition).

The Generative Ontology framework ensured:

| Requirement | How It Was Enforced |

|---|---|

| Complete goal specification | Minimum length constraint on goal field |

| Coherent mechanism-component alignment | Validation function checked that declared mechanisms have matching components |

| Thematic integration | Theme Weaver agent explicitly connected every mechanism to the narrative |

| Playability basics | Required fields for turn structure, uncertainty source, end condition |

| Balance review | Balance Critic agent with “break this” professional anxiety |

The output is not merely plausible. It is playable. A designer could take this output, build a prototype, and begin playtesting. The ontology grammar guaranteed that all the essential elements of a game are present and coherent.

But a single compelling example does not prove that the framework works in general. Does Generative Ontology reliably produce better designs than unconstrained LLM generation?

Does It Work? The Evidence

Figure. Generative Ontology enables AI to speak the lingua franca of experts, a partner that understands the grammar of the domain.

In our formal study [12], we conducted three experiments to measure whether Generative Ontology reliably improves AI-generated game designs.

Study 1: Ablation — What Does Each Layer Contribute?

We generated 120 game designs across four conditions, progressively adding layers of the Generative Ontology framework:

| Condition | Configuration | Structural Errors | Creative Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 Baseline | Raw LLM, no schema | 5.03 errors/design | Low (fun: baseline) |

| C2 Schema | Pydantic validation only | 0.10 errors/design | Low |

| C3 Ontology | Schema + ontology, single agent | 0.00 errors | Moderate |

| C4 Pipeline | Full: schema + ontology + multi-agent | 0.00 errors | High |

The results are stark. Schema validation alone eliminates nearly all structural errors (Cohen’s d = 4.78). But structural validity does not guarantee creative quality. The leap from C3 to C4, adding the multi-agent pipeline with specialized anxieties, is where creative quality emerges:

- Fun rating: d = 1.12 (p < .001)

- Strategic depth: d = 1.59 (p < .001)

- Elegance: d = 1.14 (p < .001)

- Tension and drama: d = 0.79 (p < .05)

In plain terms: the ontology provides structural validity; the multi-agent pipeline provides creative quality. Neither alone suffices. The framework needs both layers.

Study 2: Benchmark — How Close to Published Games?

We then compared 30 pipeline-generated designs against 20 published board games (CATAN, Dune: Imperium, Wingspan, and others), evaluated across the same creative dimensions:

| Dimension | Published Games | Generated Designs | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fun Rating | 8.9 | 8.1 | Moderate |

| Strategic Depth | 8.9 | 8.1 | Moderate |

| Tension & Drama | 8.5 | 8.2 | Near parity |

| Social Interaction | 7.2 | 6.9 | Near parity |

| Elegance | 9.3 | 8.0 | Notable |

| Replayability | 9.1 | 7.6 | Notable |

Generated designs consistently score in the 7-8 range (good, playable first drafts) while published games score 8-9 (polished, playtested products). The gap is real but expected: published games have undergone months or years of human iteration. What matters is that the generated designs achieve near-parity on tension/drama and social interaction, the experiential qualities that make games feel engaging.

One surprising finding: generated designs had fewer structural consistency errors (1.27) than published games (2.80, d = 0.76). The ontology enforces a level of internal coherence that even professional designers sometimes overlook.

What the Evidence Tells Us

The experiments confirm the core thesis: structure enables creativity. Raw LLMs produce fluent but structurally broken output. Schema validation fixes structure but not quality. The full Generative Ontology pipeline, with ontology constraints, multi-agent specialization, and validation loops, produces designs that are both structurally sound and creatively engaging. The formal treatment with full statistical analysis is available in our paper [12].

Beyond Games: Generative Ontology as a General Framework

The tabletop game domain was our proving ground, but the pattern is not specific to games. Generative Ontology applies wherever three conditions hold:

- The domain has established structure. There exists a vocabulary of types, relationships, and constraints that experts use to reason about the domain.

- Valid outputs must satisfy cross-field constraints. Correctness is not just a matter of individual fields being well-formed, but of relationships between fields being coherent.

- Creative generation within structure has value. The goal is not retrieval or summarization but the production of novel outputs that conform to domain rules.

Medical summaries require that diagnoses align with reported symptoms and prescribed treatments [5]. Legal contracts require that defined terms appear in operative clauses. Software architectures require that declared interfaces match their implementations. Recipe generation requires that ingredient quantities yield a dish that actually works.

In each case, an unconstrained LLM produces fluent output that may violate domain constraints. And in each case, an ontology, encoded as executable schema, can provide the grammar that makes valid generation possible. The multi-agent pattern extends naturally: a medical ontology might decompose into diagnostic, treatment, and contraindication agents with their own professional anxieties.

The insight is general: domain ontologies are not just tools for understanding. They are grammars for creation. Any domain with sufficient structure can be made generative.

Concluding Remarks

Across this series, we have traced an arc: from analyzing games (Part 4) to generating them (Part 5) to understanding why structured generation works (Part 6) to collaborating with designers in real time (Part 7). This final article has provided the theoretical synthesis and the empirical evidence.

In Whitehead’s terms [1], we have given eternal objects, the abstract patterns of game design, a computational mechanism for concrescence, the synthesis of familiar forms into novel actualities [2]. Generative Ontology is creative advance made operational.

Much remains to explore. Can AI systems induce ontologies from corpora of successful examples, learning generative grammars from exemplars rather than encoding them by hand? Can the generated designs be simulated and playtested automatically, closing the loop between generation and evaluation? These are open research questions. But the foundation is established: structured knowledge, made alive, enables structured creation.

The grammar does not write the poem. But without grammar, there is no poem to write. And now, we have evidence that the grammar works.

- Unlocking the Secrets of Tabletop Games Ontology (Part 4)

- Introducing GameGrammar: AI-Powered Board Game Design (Part 5)

- GameGrammar: The Theory of Generative Board Game Design (Part 6)

- Nova: The AI Co-Designer That Learns Your Taste (Part 7)

- » Generative Ontology: From Game Knowledge to Game Creation (Part 8)

References

[1] Alfred North Whitehead. Process and Reality. Free Press, 1929/1978.

- Foundation for the eternal objects / actual occasions framework

[2] Timothy Barker. Artificial Creativity: A Process Philosophy of Technology Perspective. Journal of Continental Philosophy, 2024.

- Connects Whitehead’s process philosophy to generative AI creativity

[3] Geoffrey Engelstein and Isaac Shalev. Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design: An Encyclopedia of Mechanisms. CRC Press, 2020.

- The comprehensive taxonomy underlying our game ontology

[4] Natalya F. Noy and Deborah L. McGuinness. Ontology Development 101. Stanford University.

- Foundation for ontology design principles

[5] Jorge Martínez-Gil, et al. Ontology-Constrained Generation of Domain-Specific Clinical Summaries. arXiv:2411.15666, Nov 2024.

- Closest methodological precedent using ontology-guided constrained generation

[6] Roberto Gallotta, et al. Large Language Models and Games: A Survey and Roadmap. arXiv:2402.18659, Feb 2024.

- Comprehensive survey of LLM applications in games

[7] Matthew Guzdial, et al. Boardwalk: Towards a Framework for Creating Board Games with LLMs. arXiv:2508.16447, 2025.

- Board game code generation from rules (contrasts with our design generation approach)

[8] Benny Cheung. Unlocking the Secrets of Tabletop Games Ontology. Feb 2025.

- Part 4 of the Game Architecture series, foundation for this post

[9] Benny Cheung. Process Philosophy for AI Agent Design. Jan 2026.

- Whiteheadian framework connecting to creative advance

[10] GameGrammar. Dynamind Research, 2026.

- AI-powered tabletop game design platform built on Generative Ontology

[11] Neural Race on GameGrammar. Dynamind Research, 2026.

- Interactive display of the complete generated game ontology from the case study in this article

[12] Benny Cheung. Generative Ontology: When Structured Knowledge Learns to Create. arXiv:2602.05636, Feb 2026.

- Formal paper with ablation study (120 designs), benchmark comparison, and evaluator reliability analysis