artwork by Stable Diffusion AI

Spatial Reasoning Under Uncertainty

Spatial reasoning is a critical aspect of many real-world applications, including urban planning, environmental monitoring, and transportation logistics. It involves the processing and interpretation of spatial data to understand and analyze the relationships between objects in a given space. Traditional GIS systems and geometric processing algorithms often assume that spatial data is precise and accurate. However, real-world spatial data is often imprecise, and incorporating this uncertainty into spatial reasoning can lead to more robust and reliable results. The ability to handle imprecise spatial data, much like human cognitive abilities, is a valuable asset in the field of spatial reasoning and analysis.

[2024/10/04] We can listen to this article as a Podcast Discussion, which is generated by Google’s Experimental NotebookLM. The AI hosts are both funny and insightful.

images/spatial-reasoning-under-uncertainty/Podcast_Spatial_Reansoning_under_Uncertainty.mp3

Figure. Illustraing the complexity of spatial reasoning under uncertainty. (image credit: Stable Diffusion AI)

Throughout the post, we will provide imaginary town of “Sensorville” as the examples to illustrate the importance of accounting for uncertainty in spatial decision-making processes. By the end of this article, you will have gained valuable insights into the methods and techniques used to navigate spatial reasoning under uncertainty and their potential applications in various domains.

In our previous discussion titled Spatial Reasoning in AGI - Insights from Philosophical Perspectives, we highlighted the critical role of spatial reasoning abilities for achieving Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). It has become evident that current Large Language Models (LLMs) fall short in spatial comprehension, which is essential for tackling numerous practical challenges. The trend is now shifting towards the incorporation of Knowledge Graph techniques to enhance LLMs with a more concrete connection to the real world. For those who are keenly following this development, the article provides valuable insights on constructing Knowledge Graphs that incorporate spatial relationships amidst uncertainty.

Outline

- Introduction

- Spatial Reasoning with Mereology and Mereotopology

- Dempster-Shafer Theory for Uncertain Spatial Reasoning

- Concluding Remarks

- References

Spatial Data Uncertainty

Spatial data uncertainty is a critical aspect to consider when dealing with real-world applications like urban planning, land use decision-making, and infrastructure requirements. Unlike the textbook GIS and computational geometry, real-world data often contains uncertainties that can significantly impact analysis and decision-making processes. By understanding the sources of uncertainty, we can determine whether to address them upfront or incorporate spatial reasoning techniques to resolve them during processing.

The uncertainty can be arises from many sources, including measurement errors, attribute inconsistencies and geometric uncertainties. The data collection process can easily be tinted with incomplete or missing data, data quality issues and data integration challenges can all contribute to uncertainty in spatial processing tasks.

When spatial data cannot be resolved upfront by eliminating the causes of uncertainty, it is crucial for us to develop strategies to manage it. To understand the problem more initutively, let’s tell the story of Sensorville.

The Story of Imaginary Town - Sensorville

Once upon a time, in a bustling city named Sensorville, a group of urban planners were faced with the challenge of installing a new network of emergency sensors to protect the residents from a variety of potential hazards such as earthquakes, floods, and fires. The city was divided into numerous distinct zones, each with its unique characteristics, risk levels, and spatial layouts.

Figure. Illustrate a group of urban planners in the city of Sensorville. (image credit: Stable Diffusion AI)

The head of the planning team, Dr. Mereo, was an expert in spatial reasoning and mereology. He knew that by understanding the relationships between the zones and their parts, as well as reasoning about the spatial properties of the environment, they could make informed decisions on where to place the sensors.

We shall see how the story developed.

Spatial Reasoning with Mereology and Mereotopology

Spatial reasoning is a broader concept that encompasses the ability to understand, manipulate, and draw conclusions about objects and their spatial relationships. Inherently, it does not have a built-in theoretical formulation. Through the field’s historically development, we found Mereology and Mereotopology provide the necessary theoretical frameworks to represent and reason about spatial relationships and address the uncertainties in spatial data. In this section, we will introduce these concepts with minimum symbolic notations to discuss their potential applications in handling spatial uncertainty.

Mereology: The study of part-whole relationships

Mereology is a branch of formal ontology that deals with the study of part-whole relationships. It offers a set of axioms and principles to describe and reason about the composition and decomposition of spatial objects. Some of the key principles in mereology include reflexivity, antisymmetry, transitivity, and supplementation.

Taking the predicate constant, $P$, to be interpreted as the parthood relation.

(P.1) Reflexivity: Every object is a part of itself. $A \le A$ , in predicate $P(x,x)$

- Example: Your finger is part of your finger.

(P.2) Antisymmetry: If an object A is a part of object B and object B is a part of object A, then object A and object B are identical. $(A \le B \land B \le A) \rightarrow A = B$, in predicate $((P(x, y) \land P(y, x)) \rightarrow x = y$

- Example: Your finger is part of your hand, but your hand is not part of your finger.

(P.3) Transitivity: If an object A is a part of object B, and object B is a part of object C, then object A is a part of object C. $(A \le B \land B \le C) \rightarrow A \le C$, in predicate $((P(x, y) \land P(y, z)) \rightarrow P(x,z)$

- Example: Your finger is part of your hand, and your hand is part of your body, so your finger is part of your body.

Given the basic mereological axioms (P.1) - (P.3), we can introduce additional mereological predicates by definition. For example,

- Equality: ($EQ$) between two entities $x$ and $y$ is defined as $x$ being a part of $y$ ($P(x, y)$) and $y$ being a part of $x$ ($P(y, x)$).

- Proper Parthood: ($PP$) between two entities $x$ and $y$ is defined as $x$ being a part of $y$ ($P(x, y)$) and $x$ not being equal to $y$ ($\lnot (x = y)$).

- Proper Extension: ($PE$) between two entities $x$ and $y$ is defined as $y$ being a part of $x$ ($P(y, x)$) and $x$ not being equal to $y$ ($\lnot (x = y)$).

- Overlap: ($O$) between two entities $x$ and $y$ is defined as the existence of an entity $z$ such that $z$ is a part of both $x$ and $y$ ($P(z, x) \land P(z, y)$).

- Underlap: ($U$) between two entities $x$ and $y$ is defined as the existence of an entity $z$ such that both $x$ and $y$ are parts of $z$ ($P(x, z) \land P(y, z)$).

These additional predicates help describe more complex relationships between entities in a mereological system.

Figure. An intuitive model for these relations, with Parthood $P$ interpreted as spatial inclusion. To read the diagram table, $y$ is assumed to be $x_4$ , then the mereological relation between $x_n$ to $y$ are displayed as $+$ True or as $-$ False (image credit: Mereology, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

Mereological principles provide a solid foundation for understanding and formalizing part-whole relationships in the spatial domain. By applying these principles, we can develop a rigorous approach to spatial reasoning that accounts for the complexities of real-world spatial data.

For instance, the reflexivity principle (P.1) states that every spatial object is a part of itself. This principle can be applied to understand that any region within a city, such as a neighborhood, is also a part of the city as a whole. Similarly, the transitivity principle (P.2) allows us to reason about spatial relationships across multiple levels of granularity. If a building is part of a block and the block is part of a district, then we can deduce that the building is also part of the district.

The antisymmetry principle (P.3) ensures that two spatial objects can only be considered equal if they are part of each other. This principle can be useful in spatial data management and analysis, as it helps to maintain the consistency and integrity of spatial data by preventing the duplication of spatial objects.

By leveraging mereological principles in conjunction with other spatial reasoning techniques such as topological relationships, we can create a robust framework for analyzing complex spatial scenarios.

Mereotopology: Combining Mereology with Topology

Mereotopology, as a formal framework, offers a comprehensive approach to spatial reasoning by combining the strengths of mereology (part-whole relationships) with topology (the study of spatial properties preserved under continuous transformations). This integration allows for a more nuanced and expressive representation of spatial relationships between objects, enabling more accurate spatial analysis and decision-making.

The focus of mereotopology is on the representation and reasoning of spatial regions, their constituent parts, and the topological relationships between them. Regions serve as the fundamental building blocks in mereotopology, and their relationships are determined by examining the properties of their boundaries and interiors.

By combining mereological concepts, such as parthood and overlap, with topological concepts, such as connection and disjointness, mereotopology offers a powerful means of capturing complex spatial relationships.

There are several key mereotopological relationships (there are many more). For examples,

-

Parthood ($\leq$): A region $A$ is a part of region $B$ ($A \leq B$) if and only if $A$ is a subregion of $B$. This relationship is reflexive ($A \leq A$), antisymmetric (if $A \leq B$ and $B \leq A$, then $A = B$), and transitive (if $A \leq B$ and $B \leq C$, then $A \leq C$).

-

Proper parthood ($<$): A region $A$ is a proper part of region $B$ ($A < B$) if $A$ is a part of $B$, and $A$ is not equal to $B$.

-

Overlap ($O$): Two regions $A$ and $B$ overlap ($A O B$) if and only if they have a common subregion. If two regions share a common part, they are said to overlap.

-

Connection ($C$): Two regions $A$ and $B$ are connected ($A C B$) if and only if their boundaries or interiors intersect. Connection is the most basic topological relationship in mereotopology and can be used to define other topological relationships such as disjointness, tangential proper parthood, and external connection.

-

Disjointness ($D$): Two regions $A$ and $B$ are disjoint ($A D B$) if and only if they are not connected.

Mereotopology can be used in situation where the reasoning about the spatial relationships between objects is crucial. It provides a qualitative and abstract way to represent and reason about spatial information, which can be advantageous in situations where precise numerical coordinates are not available or are not necessary.

Computational Mereotopology: the Region-Connection Calculus

Mereotopology provides a more general framework on the connection between regions. Mereotopology is flexible and can be extended to include more relationships, depending on the application.

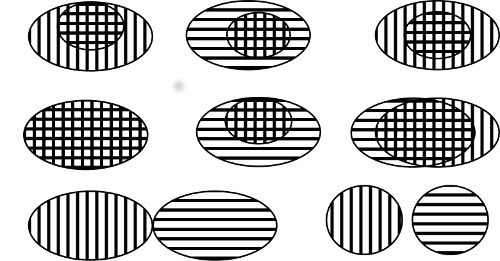

RCC-8 is a specific instantiation of the Region Connection Calculus, which provides a more fine-grained description of spatial relationships. RCC-8 defines 8 basic topological relationships between regions: disconnected (DC), externally connected (EC), equal (EQ), partially overlapping (PO), tangential proper part (TPP), tangential proper part inverse (TPPi), non-tangential proper part (NTPP), and non-tangential proper part inverse (NTPPi).

RCC-8 is superior for applications that require precise computations and detailed topological relationships, while mereotopology is more advanced for handling uncertainty and imprecise geometry.

Figure. Eight possible relations between regions in RCC, one shaded vertically and one horizontally (image credit: John G. Stell, Mereotopology and Computational Representations of the Body).

Mereotopology in Python

There is no specific Python module dedicated solely to mereotopology. However, we can use existing spatial libraries such as Shapely, which provides geometric operations and spatial relationships, and apply mereotopological concepts within your code.

Shapely can handle various spatial relationships and operations, such as intersection, union, and difference, which can be useful when working with mereotopological concepts.

Here’s an example of using Shapely to determine some mereotopological relationships:

from shapely.geometry import Polygon

# Define two regions as polygons

region_A = Polygon([(0, 0), (3, 0), (3, 3), (0, 3)])

region_B = Polygon([(2, 2), (5, 2), (5, 5), (2, 5)])

# Parthood (A is a part of B)

parthood = region_A.within(region_B)

print(f"Parthood: {parthood}")

# Proper parthood (A is a proper part of B)

proper_parthood = region_A.within(region_B) and not region_A.equals(region_B)

print(f"Proper parthood: {proper_parthood}")

# Overlap (A and B have a common subregion)

overlap = region_A.intersects(region_B)

print(f"Overlap: {overlap}")

# Connection (A and B are connected)

connection = region_A.touches(region_B) or overlap

print(f"Connection: {connection}")

# Disjointness (A and B are disjoint)

disjointness = region_A.disjoint(region_B)

print(f"Disjointness: {disjointness}")

While Shapely does not directly support mereotopological relationships, you can use its functionality to determine these relationships by applying the corresponding geometric and topological operations.

Mereotopological Theorem

With a robust theoretical foundation in place, we gain the ability to derive theorems that support more intricate reasoning tasks. Mereotopology offers a wealth of valuable theorems that facilitate a deeper understanding of spatial relationships and enable more effective reasoning about them. Some of the noteworthy theorems from mereotopology include:

- Boundary Connection Theorem: If two regions A and B are connected, then their boundaries either coincide or intersect. This theorem establishes a relationship between the connection of regions and their boundaries.

- Example: Parcels A and B share a common boundary (e.g., a road or a fence). We know that there exists a region D that is part of both A’s and B’s boundaries. This information can be used for planning purposes, such as determining the placement of utility lines or sidewalks.

- Whitehead’s Principle: If regions A and B are connected and their interiors do not overlap, then one is a part of the other’s boundary. This principle relates the connection of regions and the relationship between their interiors and boundaries.

- Example: Parcels A and B are connected, and their interiors do not overlap (i.e., they are adjacent but not overlapping). We can deduce that one of the parcels, say A, is a part of the other’s boundary, B. This information is essential for understanding how the parcels are situated relative to each other and can guide decisions about zoning or the placement of shared infrastructure.

- Fusion Theorem: If two regions A and B have a common part C, there exists a region D which is the sum (fusion) of A and B. This theorem allows us to combine overlapping regions into a single region.

- Example: The city plans to build a park, which will include parts of all three parcels: A, B, and C. However, the park must be a single connected region. We can determine that there exists a region P (the park) that is the sum of parts from parcels A, B, and C. This ensures that the park will be a single connected region, as required by the city planners.

- Transitive Connection Theorem: If regions A, B, and C are connected, and region A is connected to region C, then regions A and B must also be connected. This theorem is useful for reasoning about connections between multiple regions.

- Example: Parcels A and C are not connected, but parcel B is connected to both A and C. We know that if there were another region, say D, that connects both A and C, then A and C must also be connected. Since A and C are not connected, we can infer that no such region D exists. This information can help planners understand the spatial relationships among these parcels and can be crucial for determining access routes, transportation, or connectivity between different areas of the city.

These theorems, along with other concepts and principles in mereotopology, provide a foundation for reasoning about spatial relationships, such as parthood, connection, and overlap.

Back to the Story of Sensorville

Dr. Mereo and his team began by using spatial reasoning to analyze the spatial properties of each zone. They considered factors such as the density of buildings, their types, and how they were interconnected. They also considered the city’s infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, and tunnels, and how they impacted the movement of emergency vehicles.

The team then applied Mereolotopology to identify connections and relationships between the zones and their parts. This allowed them to prioritize the most critical areas within each zone and determine how these areas were related to one another to address spatial reasoning under uncertainty:

-

Qualitative spatial reasoning: By concentrating on qualitative relationships between spatial objects, Mereotopology provides robust and reliable reasoning in the presence of uncertain or imprecise data.

-

Consistency checking: Mereotopological reasoning helps identify inconsistencies or contradictions in spatial data, enabling the detection and correction of errors or uncertainties.

-

Spatial decision-making: Mereotopology’s formal frameworks support decision-making processes under uncertainty by offering a structured representation of spatial relationships and facilitating the exploration of alternative scenarios or solutions.

As they were working on the problem, Dr. Shafer, a renowned expert in the Dempster-Shafer Theory, joined the team. He suggested that by using his theory, they could calculate the certainty of a zone being under emergency based on the available sensor data and other spatial factors. Dr. Shafer explained the concept of belief functions and how they could be used to fuse information from different sources, such as the partial coverage provided by the sensors and the spatial properties of the zones.

Dempster-Shafer Theory for Uncertain Spatial Reasoning

The Dempster-Shafer theory, also known as the theory of evidence, is a powerful mathematical framework for managing uncertainty and reasoning with incomplete or conflicting information. In this section, we will introduce the Dempster-Shafer theory and discuss how it can be applied to uncertain spatial reasoning.

Basic Concepts of Dempster-Shafer Theory

The Dempster-Shafer theory represents uncertain information using belief functions, which are a generalization of probability functions. It uses the concept of mass functions to assign a measure of belief to different sets of possible outcomes. The key components of the Dempster-Shafer theory are:

We covered Dempster-Shafer Theory in greater details in our previous article, Dempster-Shafer Theory for Classification using Python.

- Frame of discernment: A finite set of mutually exclusive and exhaustive hypotheses that describe the possible states of a system.

- Mass function: A function that assigns a belief mass to each subset of the frame of discernment, representing the degree of belief in that particular subset.

- Belief and plausibility functions: Derived from mass functions, these functions quantify the degree of belief and plausibility, respectively, associated with each hypothesis in the frame of discernment.

One of the main strengths of the Dempster-Shafer theory is its ability to combine multiple pieces of evidence, even when they are conflicting or uncertain. The Dempster’s rule of combination provides a mechanism for updating beliefs by merging multiple mass functions, resulting in a new mass function that represents the combined evidence.

Continue to the Story of Sensorville

The team collaborated and devised a strategy. They used spatial reasoning and mereology to determine the most critical areas within each zone and how they were related to one another. Then, they applied the Dempster-Shafer Theory to compute the certainty of each zone being under emergency, based on the sensor data from partially covered areas and the spatial properties of the zones.

Figure. Imagine a group of urban planners monitoring with all the advanced tools with spatial reasoning. (image credit: Stable Diffusion AI)

With the addition of the Dempster-Shafer theory can be used to handle uncertainties in spatial data and reasoning tasks, such as:

-

Data fusion: Combining spatial data from multiple sources, which may be uncertain or conflicting, to generate a more accurate and reliable representation of the spatial relationships.

-

Uncertainty propagation: Modeling the propagation of uncertainty through spatial processes, such as spatial transformations, measurements, or analysis operations.

-

Decision-making: Supporting decision-making processes under uncertainty by providing a formal framework for reasoning with uncertain spatial information.

As the sensors were installed, the team continuously analyzed the incoming data and updated the belief functions for each zone. They also used spatial reasoning to adapt their decisions in real-time, accounting for changes in the environment, such as construction or road closures. By doing so, they were able to make informed decisions and allocate resources efficiently during emergencies, keeping the residents of Sensorville safe and secure.

Concluding Remarks

Spatial reasoning under uncertainty is a critical aspect of many real-world applications and decision-making processes. As we have seen throughout this article, several techniques, such as Mereology, Mereotopology, and Dempster-Shafer theory can help address the challenges posed by uncertain spatial data and relationships. By understanding and applying these methods, practitioners can effectively analyze and reason about complex spatial problems, even when faced with incomplete or imprecise information.

In practical applications like urban planning and environmental monitoring, the use of these techniques can lead to more informed decisions and better management of resources. Moreover, advancements in NLP and AI technologies can further support the integration of these methods into real-world workflows, enabling practitioners to efficiently process large volumes of uncertain spatial data and derive valuable insights from them.

In conclusion, spatial reasoning under uncertainty is an essential and evolving field, with promising potential for addressing complex problems in various domains. By continuing to explore and develop new techniques and methodologies, researchers and practitioners can enhance our understanding of spatial relationships and drive more effective decision-making in the face of uncertainty.

References

These references provide a solid foundation for readers. By studying these materials, readers can develop a deeper understanding of spatial reasoning under uncertainty and explore its applications across various fields.

Mereology

- Mereology, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Feb 12, 2016.

- This provides a comprehensive overview of historical and current development on Mereology.

- Carneades.org, Mereology (Basic), video, Mar 23, 2014.

- This video provides one of the best and easy way to explain Mereology.

- Roberto Casati & Achille Varzi, Parts and Places, Bradford Books, Jan 2003. ISBN: 978-0253345707

Mereotopology

- Location and Mereology, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Mar 12, 2018.

- This provides a comprehensive overview of historical and current development on Mereotopology.

-

John G. Stell, Mereotopology and Computational Representations of the Body, Computational Culture, Nov 28, 2017.

-

Randell, D. A., Cui, Z., & Cohn, A. G. (1992). A Spatial Logic Based on Regions and Connection. In KR (Vol. 92, pp. 165-176).

- Grigni, M., Papadias, D., & Papadimitriou, C. H. (1995). Topological Inference. In IJCAI (Vol. 95, pp. 901-906).

Dempster-Shafer Theory

-

Shafer, G. (1976). A mathematical theory of evidence (Vol. 1). Princeton University Press.

-

Karl Sentz and Scott Ferson, Combination of Evidence in Dempster-Shafer Theory, Sandia National Laboratories Report, April 2002

-

Richard Bowles, Dempster-Shafer Theory, video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=51ssBAp_i5Y

- This is the best explanation of D-S theory on the internet, with illustrative examples and sufficient mathematics to comprehend.

- Slides download at http://www.richardbowles.co.uk/ai_with_js/code11/#slides

Geographic Information System

-

Freksa, C., & Barkowsky, T. (1996). On the relation between spatial concepts and geographic objects. In International Conference on Geographic Information Science (pp. 115-131). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

-

Hunter, G. J., & Goodchild, M. F. (1997). Modeling the uncertainty of slope and aspect estimates derived from spatial databases. Geographical Analysis, 29(1), 35-49.

-

Longley, P. A., Goodchild, M. F., Maguire, D. J., & Rhind, D. W. (2011). Geographic Information Systems and Science. John Wiley & Sons.

-

Smith, B., & Mark, D. M. (1998). Ontology and geographic objects: An empirical study of cognitive categorization. In International Conference on Spatial Information Theory (pp. 283-298). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

-

Worboys, M., & Duckham, M. (2004). GIS: A Computing Perspective. CRC Press.

Related Post

-

Benny Cheung, Spatial Reasoning Explained, Benny’s Mind Hack, Dec 2016.

-

Benny Cheung, Geospatial Granular Computing, Benny’s Mind Hack, Dec 2018.

-

Benny Cheung, Dempster-Shafer Theory for Classification using Python, Benny’s Mind Hack, Aug 2020.

-

Benny Cheung, Spatial Reasoning in AGI - Insights from Philosophical Perspectives, Benny’s Mind Hack, Mar 2023.