artwork by Style of Byzantine mosaics transfer to many faces

Attribute-based Encryption for Healthcare Blockchain

It’s no surprise that one of the greatest concerns for a healthcare provider is data security. One can argue that the data ownership is the most important asset in this information age. Healthcare patients are aware of the value of their personal information. As a result, a healthcare provider required to switch from a centralized ownership to a distributed ownership. The patient now has the full control of his health data while the provider only has permission to access to the data when necessary.

[2024/10/05] We can listen to this article as a Podcast Discussion, which is generated by Google’s Experimental NotebookLM. The AI hosts are both funny and insightful.

images/attribute-based-encryption-for-healthcare-blockchain/Podcast_Blockchain_ABE.mp3

Provided that a section of the private data is obscured before usage, a patient could be incentivized to share part of their health related data for the advancement of medical research. In order to make this decentralized data ownership and sharing work, it requires a new technique to protect the data privacy and provide a secure system.

Figure. Artistic style of Kandinsky transfer to a healthcare blockchain image

Our previous article on “Why Blockchain for Healthcare?” explained how to use blockchain to share data with the permissioned parties. In this article, we’ll expand on the discussion of healthcare data sharing, with a focus on the data privacy through Attribute-based Encryption. When a patient decided to share part of his/her health data, the data is recorded into a blockchain confidentially. Only the permissioned parties can decrypt the shared data.

As we explore the concept and practice of attribute-based encryption for healthcare blockchain, we’ll go through the following topics from a system perspective, simplifying the mathematical aspects. Of course, for the mathematically inclined readers, the original papers are listed in the References section for a deeper understanding.

- [

</style>

](#-include-open-embedhtml-)

- Personal Health Record (PHR) Security

- Attribute-based Encryption (ABE)

- ABE Experiment with Python

- References

Personal Health Record (PHR) Security

To start our journey into this new sharing convention, Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) is the industry standard for fast and efficient storage/retrieval of health data. Units of health data in FHIR are referred to as “Resources”. FHIR de fines multiple such resources, such as Patient, Practitioner, Observation, MedicalRequest, etc. where each resource can be linked to multiple other resources. In the previous post on FHIR Server Up and Running, we have provided a practical tutorial to setup a FHIR RESTful API service with the simulated patient health data. As always, our philosophy of balance between theory and practice is always helpful when we need to comprehend a new concept.

While FHIR enabled health data to be published easily, inadvertent or malicious disclosure of data that contains Personally Identi able Information (PII) to unauthorized individuals or organizations may have catastrophic consequences. Thus, healthcare providers must comply with federal and state policies when they release sensitive medical data. For example, the compliance policies, such HIPAA and HITECH, must be carefully studied and enforced for auditing. Ensure data security is a definite first step towards compliance.

Attribute-based Encryption (ABE)

Attribute-based Encryption (ABE) is a relatively recent approach that reconsiders the concept of public-key cryptography [SW05][GPSW06][BSW07][Waters11]. In traditional public-key cryptography, a message is encrypted for a specific receiver using the receiver’s public-key. Identity-based cryptography and in particular identity-based encryption (IBE) changed the traditional understanding of public-key cryptography by allowing the public-key to be an arbitrary string, e.g., the email address of the receiver.

ABE goes one step further and defines the identity not atomic but as a set of attributes, e.g., roles and context, and messages can be encrypted with respect to subsets of attributes (key-policy ABE - KP-ABE) or policies defined over a set of attributes (ciphertext-policy ABE - CP-ABE). The key issue is, that someone should only be able to decrypt a ciphertext if the person holds a key for “matching attributes” where user keys are always issued by some trusted party.

Identity and Attributes

At the time of registering a patient or a practitioner, attributes can be specified for them, which then are added to their X.509 certificates upon their enrollment to a Certificate Authority (CA). Examples of attributes include a role name such as an “Patient” or “Practitioner” that is agreed upon by the organizations participating in the network. When smart contract is executed, it can extract from the identity and attributes before the invoke or query transaction. At a simple level, this also allows application-level attributes to be passed down into smart contract through a X.509 certificate. The participant’s identity and attributes are fully secured and authenticated, i.e. no one can fake their identity and attributes.

For an authenticated participant, we can find the subject’s attributes from their X.509 certificate, such as

Name;

Organization;

Position;

Role;

...

We can also add the application-level attributes, capturing the operational context, such as

Action;

IP-address;

Time;

Device;

...

Interested reader should refer to our latest article on X.509 Identity for Attribute-based Encryption, describes the practical approach to demonstrate how to use Python cryptography to generate X.509 certificate with custom atributes; subsequently, we use charm-crypto framework’s hybrid adapter to perform CP-ABE (ciphertext-policy) with the X.509 custom attributes.

Ciphertext-Policy ABE

In ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption (CP-ABE) a user’s private-key is associated with a set of attributes and a ciphertext specifies an access policy over a defined universe of attributes within the system. A user will be able to decrypt a ciphertext, if and only if his attributes satisfy the policy of the respective ciphertext. Policies may be defined over attributes using conjunctions, disjunctions and \((k,n)\) threshold gates, i.e., \(k\) out of \(n\) attributes have to be present. For instance, let us assume that the universe of attributes is defined to be \({A,B,C,D}\) and user 1 receives a key to attributes \({A,B}\) and user 2 to attribute \({D}\). If a ciphertext is encrypted with respect to the policy \((A \land C) \lor D\), then user 2 will be able to decrypt, while user 1 will not be able to decrypt.

CP-ABE are not necessarily encrypted to one particular user as in traditional public key cryptography. Instead both users’ private keys and ciphertexts will be associated with a set of attributes or a policy over attributes. A user is able to decrypt a ciphertext if there is a “match” between his private key and the ciphertext.

CP-ABE thus allows to realize implicit authorization, i.e., authorization is included into the encrypted data and only people who satisfy the associated policy can decrypt data. Another nice features is, that users can obtain their private keys after data has been encrypted with respect to policies. So data can be encrypted without knowledge of the actual set of users that will be able to decrypt, but only specifying the policy which allows to decrypt. Any future users that will be given a key with respect to attributes such that the policy can be satisfied will then be able to decrypt the data.

CP-ABE Algorithms

What we really want is to be able to define that the access is based on other things, such as his location, or whether he is the practitioner associated with a patient. These are defined as attributes for his access rights, and define attributed-based security, where we can define fine-grained control on the decryption process. For example, we might define that some sensitive health information is only accessible when the patient and the practitioner have both authenticated themselves, and are in a provable location.

CP-ABE Encryption Process

We have several stages for the encryption process [BSW07]:

- Setup. The setup algorithm takes no input other than the implicit security parameter. It outputs the public parameters \((PK)\) and a master key \((MK)\).

- Encrypt(PK, M, A). The encryption algorithm takes as input the public parameters \((PK)\), a message \((M)\), and an access structure \((A)\) over the universe of attributes. The algorithm will encrypt \((M)\) and produce a ciphertext \((CT)\) such that only a user that possesses a set of attributes that satisfies the access structure will be able to decrypt the message. We will assume that the ciphertext implicitly contains \((A)\).

- Key_Generation(MK, S). The key generation algorithm takes as input the master key (MK) and a set of attributes \((S)\) that describe the key. It outputs a private key \((SK)\).

- Decrypt(PK, CT, SK). The decryption algorithm takes as input the public parameters \((PK)\), a ciphertext \((CT)\), which contains an access policy \((A)\), and a private key \((SK)\), which is a private key for a set \((S)\) of attributes. If the set \((S)\) of attributes satisfies the access structure \((A)\) then the algorithm will decrypt the ciphertext and return a message \((M)\).

- Delegate(SK, S˜). The delegate algorithm takes as input a secret key \((SK)\) for some set of attributes \((S)\) and a set \(S˜ \subset S\). It output a secret key \((S˜K)\) for the set of attributes \((S˜)\). [Note: this function is not used in this article]

CP-ABE Encryption Sequence

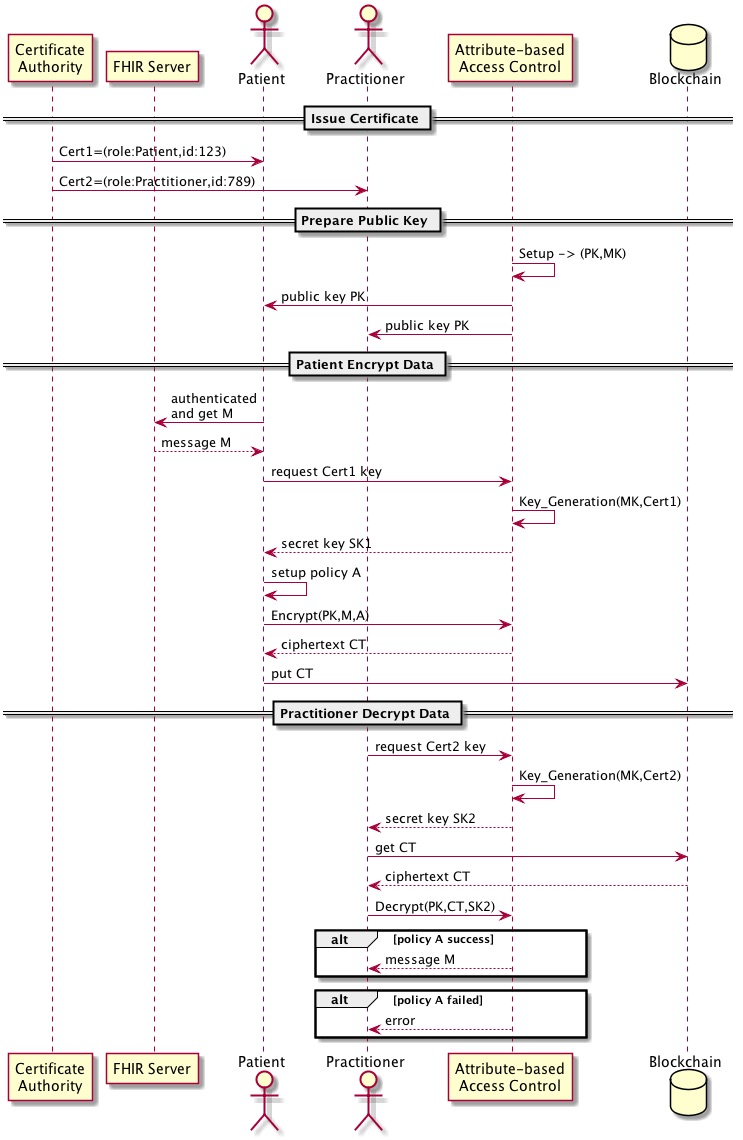

To digest how to apply this suite of CP-ABE algorithms, the following sequence diagram depicts the CP-ABE encryption process:

The Python implementation is shown in the later section ABE with Python

- Phase 1: Issue Certificates - both patient and practitioner are participating in the network, must be registered and enrolled. The certificate authority (CA) will issue the corresponding X.509 certificate to the participants. Each certificate contains the identity and attributes that described the participant precisely.

- Phase 2: Prepare Public Key - system uses the

Setupalgorithm to prepare the master key (MK) and public key (PK). The MK is only known to the attribute-based access control system for this is used to generate each participant’s secret keys. The PK is distributed to each participant for encrypting their data. - Phase 3: Patient Encrypt Data - patient authenticated and retrieved his health record (M) from FHIR server. Using patient’s certificate, the system use

Key_Generationto generate a patient’s secret key. An access policy (A) is used to encrypt the health record (M) byEncryptusing the public key (PK). The ciphertext (CT) can be put on the blockchain (or other storage system) for data sharing. - Phase 4: Practitioner Decrypt Data - Using practitioner’s certificate, the system use

Key_Generationto generate a practitioner’s secret key. After the practitioner requests for the ciphertext (CT) from the blockchain,Decryptcan be used to decrypt the ciphertext with the practitioner’s secret key. If practitioner’s secret key has satisfied the ciphertext policy (A), the health data (M) is returned; otherwise, the decryption failed with error.

Figure. The CP-ABE encryption process (1) patient and practitioner receives their credentials (2) ABAC prepared sharing keys according to respective participant credentials (3) patient encrpyted data with a policy (4) practitioner decrypted data if his secret key matched the policy

ABE on FHIR Patient Resource

For example, the “Patient” resource for smart-1032702 can be retrieved from the FHIR server.

GET http://localhost:8080/hapi-fhir/baseDstu3/Patient/smart-1032702

The FHIR server responses with the following result for smart-1032702,

{

"fullUrl": "http://localhost:8080/hapi-fhir/baseDstu3/Patient/smart-1032702",

"resource": {

"resourceType": "Patient",

"id": "smart-1032702",

"name": [

{

"use": "official",

"family": "Shaw",

"given": [

"Amy",

"V"

]

}

],

"telecom": [

{

"system": "phone",

"value": "800-782-6765",

"use": "mobile"

},

{

"system": "email",

"value": "amy.shaw@example.com"

}

],

"gender": "female",

"birthDate": "2007-03-20",

"address": [

{

"use": "home",

"line": [

"49 Meadow St"

],

"city": "Mounds",

"state": "OK",

"postalCode": "74047",

"country": "USA"

}

],

"generalPractitioner": [

{

"reference": "Practitioner/smart-Practitioner-72004454"

}

]

...

}

}

The smart contract received the patient’s record which can perform the ABE according to a policy. The ciphertexts of the patient’s record are attached to access policies and keys are associated with sets of attributes. For example, a policy \(A\) could say: the patient’s record can be decrypted by the specific patient and practitioner.

Policy A =

(Role=PRACTITIONER AND Id=SMART-PRACTITIONER-72004454) OR (Role=PATIENT AND Id=SMART-1032702)

or a policy \(A'\) could say in a greater generalization: for all practitioners working in a specific hospital.

Policy A' =

(Org=HOSPITAL AND Role=PRACTITIONER) OR (Role=PATIENT AND Id=SMART-1032702)

The fulfillment of all conditions provides access to a FHIR resource.

In this model, there is no limit to the complexity of the policy. Also, the encryption can be applied to a fine-grained control of the sensitive information, such as encrypting the birthDate or SIN number with different policies.

For further reading, readers can refer to [SM17] and [TM17] for the application of attribute-based access control for healthcare resources.

ABE Experiment with Python

Implementing ABE from scratch is challenging, we resorted to use existing Python cryptographic library and system to construct our experiment.

Our experiment is using the Python implementation of Attribute-based Encrpytion based on the Charm framework [AC17], Github repo: https://github.com/sagrawal87/ABE

The following steps will guide you through the installation and execution. The instructions are proven to work on a Mac (running OS X High Sierra).

Install Pre-requisites

PBC

PBC (Pairing-based cryptography) is a cryptographc library, website: https://formulae.brew.sh/formula/pbc

brew install pbc

...

==> Pouring pbc-0.5.14.high_sierra.bottle.tar.gz

🍺 /usr/local/Cellar/pbc/0.5.14: 35 files, 786KB

Charm

Charm is a framework for rapidly prototyping advanced cryptosystems [AGMPRGR13], Github repo: https://github.com/JHUISI/charm

Installing Charm from source is straightforward. First, verify that you have installed the following dependencies:

- GMP 5.x

- PBC

- OPENSSL

./configure.sh --enable-darwin

make install

...

Using /usr/local/anaconda3/lib/python3.5/site-packages

Finished processing dependencies for Charm-Crypto==0.50

Running the built-in test suite to ensure all crypto functions are working,

make test

ABE with Python

The following main.py was modified to run [BSW07] CP-ABE scheme.

The policy is using ((PATIENT and SMART-1032702) or (PRACTITIONER and SMART-PRACTITIONER-72004454))

- The patient attribute list is having

['PATIENT', 'SMART-1032702']so that thepatient_keyhas sufficient attributes to satisfy the policy. The cipher-text can be decrypted successfully. - Similarly, the practitioner attribute list is having

['PRACTITIONER', 'SMART-PRACTITIONER-72004454']so that thepractitioner_keyhas sufficient attributes to satisfy the policy. The cipher-text can also be decrypted successfully. - However, the practitioner#2 attribute list is having

['PRACTITIONER', 'SMART-PRACTITIONER-90000001']so that thepractitioner2_keydoes not satisfy the policy. The cipher-text decryption failed in this case.

from charm.toolbox.pairinggroup import PairingGroup, GT

from bsw07 import BSW07

def main():

# instantiate a bilinear pairing map

# 'MNT224' represents an asymmetric curve with 224-bit base field

pairing_group = PairingGroup('MNT224')

# CP-ABE under DLIN (2-linear)

cpabe = BSW07(pairing_group, 2)

# run the set up

(pk, msk) = cpabe.setup()

# generate a Patient key

patient_attr_list = ['PATIENT', 'SMART-1032702']

patient_key = cpabe.keygen(pk, msk, patient_attr_list)

# generate a Practitioiner key

practitioner_attr_list = ['PRACTITIONER', 'SMART-PRACTITIONER-72004454']

practitioner_key = cpabe.keygen(pk, msk, practitioner_attr_list)

# generate a Practitioiner#2 key

practitioner2_attr_list = ['PRACTITIONER', 'SMART-PRACTITIONER-90000001']

practitioner2_key = cpabe.keygen(pk, msk, practitioner2_attr_list)

# choose a random message pretend to be patient's record

msg = pairing_group.random(GT)

# generate a ciphertext

policy_str = '((PATIENT and SMART-1032702) or (PRACTITIONER and SMART-PRACTITIONER-72004454))'

ctxt = cpabe.encrypt(pk, msg, policy_str)

# decryption as Patient

rec_msg = cpabe.decrypt(pk, ctxt, patient_key)

if rec_msg == msg:

print ("Successful decryption as a Patient.")

else:

print ("Decryption as a Patient failed.")

# decryption as Practitioner

rec_msg = cpabe.decrypt(pk, ctxt, practitioner_key)

if rec_msg == msg:

print ("Successful decryption as a Practitioner.")

else:

print ("Decryption as a Practitioner failed.")

# decryption as Practitioner#2

rec_msg = cpabe.decrypt(pk, ctxt, practitioner2_key)

if rec_msg == msg:

print ("Successful decryption as a Practitioner#2.")

else:

print ("Decryption as a Practitioner#2 failed.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

After running main.py, we shall see the decryption is successful.

python main.py

Successful decryption as a Patient.

Successful decryption as a Practitioner.

Policy not satisfied.

Decryption as a Practitioner#2 failed..

After this experiment, we understand the practical CP-ABE techniques to ensure the patient’s data confidentiality. With sufficient integration skills and blockchain knowledge, we can even record the health data into the Hyperledger Fabric for real-life usage.

UPDATE 2020/08/17 The reader expected to encrypt any plain text message with CP-ABE. We shall provide an extended example in X.509 Identity for Attribute-based Encryption, to illustrate how to encrypt any plain text message and to decrypt with the certificate attributes

References

- [SW05] Sahai, Amit, and Brent Waters. “Fuzzy identity-based encryption.” In Eurocrypt, vol. 3494, pp. 457-473. 2005.

- [GPSW06] Goyal, Vipul, Omkant Pandey, Amit Sahai, and Brent Waters. “Attribute-based encryption for fine-grained access control of encrypted data.” In Proceedings of the 13th ACM conference on Computer and communications security, pp. 89-98. ACM, 2006.

- [BSW07] John Bethencourt, Amit Sahai, and Brent Waters. “Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption.” In Security and Privacy, 2007. SP’07. IEEE Symposium on, pp. 321-334. IEEE, 2007.

- [Waters11] Waters, Brent. “Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption: An expressive, efficient, and provably secure realization.” In Public Key Cryptography, vol. 6571, pp. 53-70. 2011.

- [AGMPRGR13] Akinyele, Joseph A., Christina Garman, Ian Miers, Matthew W. Pagano, Michael Rushanan, Matthew Green, and Aviel D. Rubin. “Charm: a framework for rapidly prototyping cryptosystems.” Journal of Cryptographic Engineering 3, no. 2 (2013): 111-128.

- [SM17] Subhojeet Mukherjee, et. al., “Attribute Based Access Control for Healthcare Resources”, ABAC ‘17 Proceedings of the 2nd ACM Workshop on Attribute-Based Access Control, pp 29-40.

- [AC17] Shashank Agrawal, and Melissa Chase. “FAME: Fast Attribute-based Message Encryption.” To appear in the Proceedings of the 24th ACM conference on Computer and communications security, 2017.

- [TM17] (video only) Tony Mallia, “Attribute Based Access Control (ABAC) in Healthcare”, Edmond Scientific Company, Cloud Identity Summit 2017.