artwork by GPT-4o

An AI-Powered Approach to Structural Abstraction - The KRA Model in Reverse Engineering

Philosophy of AI

Part 4 of 6Ever felt utterly swamped? Faced with a complex system, a mountain of data, or a dense technical document, it can feel like trying to drink from a fire hose. Raw, unfiltered information at scale is simply overwhelming. Cutting through that noise, finding the core essence, and truly understanding the heart of complex ideas is a fundamental challenge.

This is where abstraction comes in. Far from being a dusty, academic concept, abstraction is a vital, pervasive tool that shapes how we interact with the world, how we think, and critically, how we build and understand intelligent systems. Looking through the lens of the KRA (Knowledge Representation & Abstraction) model [1], and considering how AI can be leveraged, we can see abstraction not just as a philosophical notion, but as an operational necessity for navigating complexity.

Figure. Overwhelmed by Complexity: In a world of unfiltered information and intricate systems, abstraction becomes the key to clarity and understanding.

The striking thing about abstraction is its universality. Its roots literally mean “to draw away,” but its meaning has evolved. It’s not just about taking things away; it’s about purposeful simplification. “To abstract,” as Goldstone and Barsalou [4] put it, “is to distill the essence from its superficial trappings.” This process is found everywhere – in philosophy formalizing how we form abstract ideas, in mathematics finding general patterns beyond specific numbers, in natural language, in art, and in our own cognitive processes. In computer science, it is completely vital; without abstraction, we couldn’t possibly manage the sheer scale and intricacy of modern software or data structures. We’d be drowning in the weeds.

This article closely aligns with the ideas presented by Saitta and Zucker in “Abstraction In Artificial Intelligence And Complex Systems” [1] while adding our own perspective on how abstraction can be practically applied in the context of reverse engineering [2,3].

Abstraction in AI

And while its presence is felt across many domains, abstraction becomes absolutely essential when we talk about Artificial Intelligence. For AI to tackle really tough problems - planning complex sequences of actions, solving large-scale constraint satisfaction problems like scheduling, representing vast amounts of knowledge, or enabling agents (like robots) to function in the real world; it cannot operate solely on ground-level detail. It needs abstract views. As we surveyed recent researches, abstraction isn’t merely a nice-to-have for advanced AI; it’s foundational. Without a solid grasp and application of abstraction, much of the sophisticated AI we envision simply wouldn’t be possible.

Figure. Abstraction across Disciplines: Highlighting its fundamental role in Philosophy, Mathematics, Art/Natural Language, and Computer Science.

Given its importance, defining abstraction precisely is, perhaps fittingly, tricky. There isn’t one single universally agreed-upon definition. Different theories focus on different aspects: syntactic approaches look at manipulating the structure of information (like summarizing text by shortening sentences), while semantic approaches focus on preserving meaning (ensuring the summary captures the core message). Related concepts like granularity (the level of detail, like looking at a city map vs. a street map) and reformulation (changing the representation, like discussing spending trends instead of listing individual purchases) interact with abstraction, but abstraction’s core characteristics set it apart.

Key among these characteristics is information reduction – deliberately removing details irrelevant to the current goal. It’s also often an intensional property, relating to concepts and meanings rather than specific instances. Critically, abstraction is relative; what’s abstract depends entirely on the context and the purpose. It’s fundamentally a process, an active transformation, not a static state. And it crucially involves information hiding, intentionally concealing details to simplify focus. While generalization (finding common features to group things) or approximation (replacing precise info with something less exact) are related, abstraction uniquely combines information reduction with purposeful focus on the essential for a specific task.

The KRA Model: A Framework for Operational Abstraction

Okay, so we understand the concept, but how do we do it, especially in a structured way for AI? This is where the KRA model [1] comes in. Presented as a central framework, KRA provides a systematic way to understand and perform abstraction, making it operational. It defines abstraction not in a vacuum, but tied to:

- Query Environment (Q): The specific task or question driving the need for abstraction. The abstraction is performed relative to Q – what is relevant depends on what you are trying to figure out or achieve.

- Description Frame (Γ): This is the schema or vocabulary that defines the types of elements (objects, attributes, functions, relations) that can be observed and reasoned about in the system being modeled. It’s the potential structure.

- Configuration Space (Ψ): This is the universe of all possible system states or descriptions that could be built based on the Description Frame (Γ).

- Data Generation: The process by which we obtain actual information from the system – the raw observations that populate the model.

It’s distinct from the Description Frame (Γ), which is a schema of potentially observable elements, and the Configuration Space (Ψ), which is the space of all possible descriptions based on Γ. The P-Set is the concrete, observed data that populates this framework for a specific moment in time.

The P-Set: Ground Truth Data

This brings us to the heart of the observed data in KRA: the P-Set, or perception set. This is the concrete, super-detailed snapshot of the system as perceived by our “sensors.” If the Description Frame (Γ) is the blueprint, the P-Set is the actual filled-in form for a given moment.

A P-Set is formally defined as a 4-tuple: P = (O, A, F, R), where:

- O (Objects): This is the actual set of identifiers of (typed) objects observed in the system S (e.g.,

'server1'is type'server'). These are the instances of the types defined in Γ. - A (Attributes): This represents the specific instantiations of the attributes (defined in Γ) observed on the actual objects in O. It’s the collection of attribute-value pairs measured for the specific objects detected (e.g.,

('server1', 'status') = 'online'). - F (Functions): This contains the specific instantiations (i.e., the covers or sets of tuples satisfying the function) of the functions (defined in Γ) observed on the actual objects in O. It represents the observed relationships captured by functions for the detected objects. (e.g.,

calculate_distance('point A', 'point B') = 5.3). Functions map tuples of objects to values. - R (Relations): This contains the specific instantiations (i.e., the covers or sets of tuples satisfying the relation) of the relations (defined in Γ) observed on the actual objects in O. It represents the observed relationships captured by relations for the detected objects. (e.g.,

'server1' connects_to 'database alpha'). Relations describe relationships between tuples of objects (boolean truth values are implied).

In essence, the P-Set is:

- The observed data: It’s what you “perceive” from the system S.

- An instance of the Description Frame (Γ): While Γ defines the potential types, attributes, functions, and relations that could be observed, the P-Set contains the actual observed instances and values for a specific situation.

- Linked to the Configuration Space (Ψ): A P-Set is consistent with a subset of configurations in Ψ. If all observations are perfectly specified (no “UN” values), the P-Set corresponds to a single unique configuration. If there are “UN” values, it corresponds to a set of compatible configurations [1, p. 156-157].

- The starting point for abstraction in KRA: In the KRA model’s bottom-up perspective, the P-Set ($P_g$) represents the “ground truth” and is the input to the methods associated with abstraction operators (like

meth[Pg, ω]) to generate a more abstract P-Set ($P_a$) [1, p. 175, 204].

This P-Set is the granular ground truth upon which KRA abstraction operators act.

Example: E-Commerce System (Microservices Architecture)

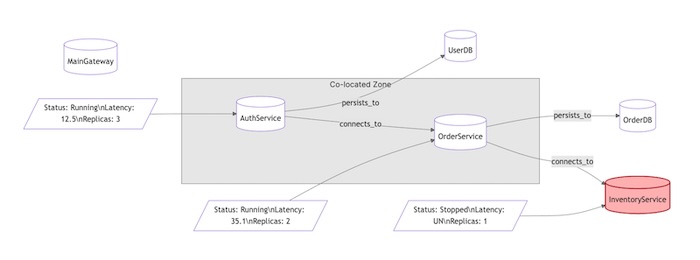

Assume we’re observing a running e-commerce system with sensors (Σ) that collect runtime architectural data. The Description Frame (Γ) defines what kinds of components, connections, and properties can exist in this system.

We might define elements in Γ such as:

- Types:

Service,Database,API Gateway - Attributes:

status(Service) -> {Running, Stopped},latency(Service) -> Float,replicas(Service) -> Int - Functions:

connects_to(Service, Service) -> Boolean,persists_to(Service, Database) -> Boolean - Relations:

co_located(Service, Service)– for services deployed in the same zone.

Now suppose your monitoring tools observe the system and generate a Concrete P-Set (Observed System State) at a given point in time:

Figure. Using a concrete P-Set example to illustrate the observed system state.

This P-Set structure gives a precise, observed instance of the e-commerce system’s architecture at runtime. It shows:

- Which services and databases exist (O)

- Their current statuses and performance metrics (A)

- How services are connected or store data (F)

- How services are physically or logically related (R)

Specifically, based on the diagram and description, the P-Set could be represented as:

1. O — Objects

O = {

s1:Service ('AuthService'),

s2:Service ('OrderService'),

s3:Service ('InventoryService'),

db1:Database ('UserDB'),

db2:Database ('OrderDB'),

gw1:API Gateway ('MainGateway')

}

(Note: In a typical P-Set, objects would likely be just IDs like ‘s1’, ‘s2’, etc., with their type explicitly listed. The descriptive name ‘AuthService’ is for clarity here.)

2. A — Attributes

A = {

('s1', 'status') = 'Running',

('s2', 'status') = 'Running',

('s3', 'status') = 'Stopped',

('s1', 'latency') = 12.5,

('s2', 'latency') = 35.1,

('s3', 'latency') = 'UN', # unknown due to service being down

('s1', 'replicas') = 3,

('s2', 'replicas') = 2,

('s3', 'replicas') = 1

}

3. F — Functions

F = {

'connects_to': [('s1', 's2'), ('s2', 's3')], # AuthService -> OrderService, OrderService -> InventoryService

'persists_to': [('s1', 'db1'), ('s2', 'db2')] # AuthService -> UserDB, OrderService -> OrderDB

}

(Note: Functions map tuples to values. If connects_to is boolean, the presence of the tuple implies True. The diagram shows these connections explicitly.)

4. R — Relations

R = {

'co_located': [('s1', 's2')] # Auth and Order are in same deployment zone

}

(Note: Similar to functions, the presence of the tuple implies the relation holds.)

KRA Abstraction Operators

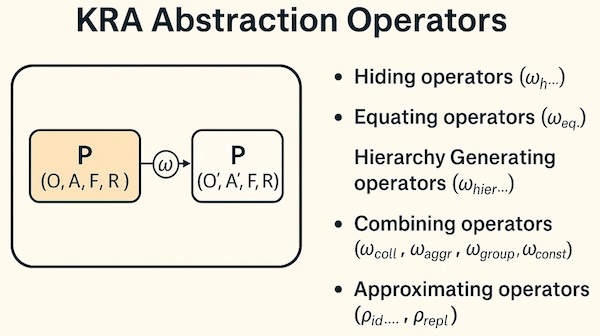

The KRA Abstraction Operators [1, p. 203+] are the tools for performing this transformation from a detailed P-Set ($P_g$) to a more abstract one ($P_a$). Defined conceptually at the level of the Description Frame (Γ), they have corresponding methods (meth) that apply the transformations to the actual data in the P-Set. These methods, structured to modify the O, A, F, and R components of the P-Set, perform the “distilling.”

The operators are categorized by their mechanism [1, p. 204-209]:

Figure. KRA Abstraction Operators transform a P-Set P(O,A,F,R) into an abstract P-Set P’(O’,A’,F’,R’) via a method ω.

- Hiding operators (

ωh...): Selectively remove elements, attributes, attribute values, function definitions, relation definitions, or arguments from the P-Set view. They make information unavailable. - Equating operators (

ωeq...): Group similar elements or values into equivalence classes. They replace multiple specific instances with a single abstract representative. - Hierarchy Generating operators (

ωhier...): Build compositional or type hierarchies. They create new, higher-level elements or attributes derived from lower-level ones. - Combining operators (

ωcoll,ωaggr,ωgroup,ωconstr): Group multiple existing things into a single entity or construct new elements based on existing ones. They aggregate information. - Approximating operators (

pid...,prepl): Replace precise information with less exact, representative values, often losing some fidelity but gaining simplicity. They change the detail level of information.

Here is a summary table derived from the KRA model literature [1, Appendix E Table E.6, Chapter 7], showing the categories and specific operators:

Summary Table of Abstraction and Approximation Operators (Derived from KRA Model [1])

| Category | Operator | Type | Acts on Γ (Arguments in operator definition) | Method Acts on P | Description/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hiding | ωhobj |

Abstraction | o (object identifier) | P-Set P | Hides specific objects from view. |

ωhtype |

Abstraction | t (type identifier) | P-Set P | Hides specific types from view. | |

ωhattr |

Abstraction | (Am, Am) (attribute and its domain) | P-Set P | Hides specific attribute definitions/views. | |

ωhfun |

Abstraction | fh (function identifier) | P-Set P | Hides specific function definitions/views. | |

ωhrel |

Abstraction | Rk (relation identifier) | P-Set P | Hides specific relation definitions/views. | |

ωhfunarg |

Abstraction | fh, xj (function identifier, argument index) | P-Set P | Hides specific arguments in a function definition. | |

ωhrelarg |

Abstraction | Rk, xj (relation identifier, argument index) | P-Set P | Hides specific arguments in a relation definition. | |

ωhattrval |

Abstraction | (Am, Am), vi (attribute, domain, value) | P-Set P | Hides specific values from an attribute domain (can be used for discretization). | |

ωhfunargval |

Abstraction | fh, xj, o (func id, arg index, arg value) | P-Set P | Hides specific values in a function argument domain. | |

ωhrelargval |

Abstraction | Rk, xj, o (rel id, arg index, arg value) | P-Set P | Hides specific values in a relation argument domain. | |

ωfuncodom |

Abstraction | fh, CD(fh), v (func id, codomain, value) | P-Set P | Hides specific values from a function codomain. | |

| Equating | ωeqobj |

Abstraction | φeq, o(a) (condition, abstract object name) | P-Set P | Builds equivalence classes for objects based on a condition. |

ωeqattr |

Abstraction | φeq, (A(a), ΛΑ(a)) (condition, abstract attr) | P-Set P | Builds equivalence classes for attributes based on condition. | |

ωeqfun |

Abstraction | φeq, f(a) (condition, abstract function) | P-Set P | Builds equivalence classes for functions based on condition. | |

ωeqrel |

Abstraction | φeq, R(a) (condition, abstract relation) | P-Set P | Builds equivalence classes for relations based on condition. | |

ωeqtype |

Abstraction | φeq(t1,…, tk), t(a) (condition, abstract type) | P-Set P | Builds equivalence classes for types based on a condition. | |

ωeqattrval |

Abstraction | (Α, ΛΑ), ΛΑ,eq, v(a) (attr, domain, value set, abstract value) | P-Set P | Builds equivalence classes for attribute values (can be used for discretization). | |

ωeqfunargval |

Abstraction | fh, xj, ГО,eq, o(a) (func id, arg index, equiv set, abstract value) | P-Set P | Builds equivalence classes for function argument values. | |

ωeqrelargval |

Abstraction | Rk, xj, ГО,eq, o(a) (rel id, arg index, equiv set, abstract value) | P-Set P | Builds equivalence classes for relation argument values. | |

ωeqfuncodom |

Abstraction | fh, CD(fh), Veq, v(a) (func id, codomain, equiv set, abstract value) | P-Set P | Builds equivalence classes for function codomain values. | |

ωeqfunarg |

Abstraction | fh, Zeq, z(a) (func id, equiv set, abstract value) | P-Set P | Builds equivalence classes for function arguments (based on the set of values they take). | |

ωeqrelarg |

Abstraction | Rk, Zeq, z(a) (rel id, equiv set, abstract value) | P-Set P | Builds equivalence classes for relation arguments (based on the set of values they take). | |

| Hierarchy | ωhierattr |

Abstraction | ΓΑ,child, (A(a), Λ(a)) (child attributes, abstract attr) | P-Set P | Builds attribute hierarchies, deriving abstract attributes from child attributes. |

ωhierfun |

Abstraction | ΓF,child, f(a) (child funcs, abstract func) | P-Set P | Builds function hierarchies, deriving abstract functions from child functions. | |

ωhierrel |

Abstraction | ΓR,child, R(a) (child rels, abstract rel) | P-Set P | Builds relation hierarchies, deriving abstract relations from child relations. | |

ωhiertype |

Abstraction | ΓΤΥΡΕ, child, t(a) (child types, abstract type) | P-Set P | Builds type hierarchies, deriving abstract types from child types. | |

ωhierfuncodom |

Abstraction | fh, CD(fh)child, v(a) (func id, child codom values, abstract value) | P-Set P | Builds hierarchies for function codomain values. | |

| Combining | ωcoll |

Abstraction | t, t(a) (original type, new type) | P-Set P | Builds collective objects by grouping multiple objects of the same type. |

ωaggr |

Abstraction | (t1,…, ts), t(a) (original types, new type) | P-Set P | Aggregates objects of different types into a composite object. | |

ωgroup |

Abstraction | φgroup, G(a) (condition, abstract group name) | P-Set P | Builds group objects based on a condition (often extends ωeqobj by creating a new object for the equivalence class). |

|

ωconstr |

Abstraction | Constr, y (construction rule, new element name) | P-Set P | Constructs new description elements (attributes, functions, relations) from existing ones using a rule. | |

| Approximating | prepl |

Approximation | X(g), y, y(ap) (involved set, element, approximation) | P-Set P | Replaces a set of description elements with an approximating one. |

pidobj |

Approximation | φid, o(p) (condition, representative object name) | P-Set P | Makes a set of objects less precise by selecting a representative. | |

pidtype |

Approximation | φid (types) | P-Set P | Makes a set of types less precise. | |

pidattr |

Approximation | φid (attributes) | P-Set P | Makes a set of attribute definitions less precise. | |

pidfun |

Approximation | φid (functions) | P-Set P | Makes a set of function definitions less precise. | |

pidrel |

Approximation | φid (relations) | P-Set P | Makes a set of relation definitions less precise. | |

pidattrval |

Approximation | (Α, ΛΑ), ΛΑ,id, v(p) (attr, domain, value set, representative value) | P-Set P | Approximates attribute values (replacing a set with a representative value). | |

pidfunargval |

Approximation | fh, xj, ГО,eq, o(a) (func id, arg index, equiv set, representative value) | P-Set P | Approximates function argument values (replacing a set with a representative value). | |

pidrelargval |

Approximation | Rk, xj, ГО,eq, o(a) (rel id, arg index, equiv set, representative value) | P-Set P | Approximates relation argument values (replacing a set with a representative value). | |

pidfuncodom |

Approximation | fh, CD(fh), Veq, v(p) (func id, codomain, equiv set, representative value) | P-Set P | Approximates function codomain values (replacing a set with a representative value). | |

pidfunarg |

Approximation | fh, Zid, z(a) (func id, equiv set, representative value) | P-Set P | Approximates function arguments (based on the set of values they take). | |

pidrelarg |

Approximation | Rk, Zid, z(a) (rel id, equiv set, representative value) | P-Set P | Approximates relation arguments (based on the set of values they take). |

The operators are classified according to the mechanism they employ and the elements or values of the description frame they act upon. The main categories of abstraction mechanisms mentioned are hiding information, making information less detailed by building equivalence classes, generating hierarchies, or combining elements. Approximation operators are also included in the summary tables and are defined as those that identify sets of elements and replace them with one of their members.

Each operator concept (ω) defined on the Description Frame (Γ) has a corresponding method (meth) that implements the specific transformation logic applied to the data in a P-Set.

Example: Implementing meth_hidetype

From the Hiding category, let’s consider the ωhtype operator, which hides all information related to objects of a specific type. We want to implement its method, meth_hidetype, as a Python function that operates on a P-Set.

This Python implementation translates the described effect of the ωhtype operator via its meth_hidetype method on a P-Set structure, demonstrating how this specific abstraction operator works at the data level in the KRA model.

import copy

def meth_hidetype(pg_pset, target_type):

"""

Implementation of the meth[Pg, whtype(target_type)] method

for the whtype abstraction operator, based on KRA model structure [1, Appendix E, Chapter 7].

This method applies the "hide type" abstraction to a

specific P-Set (pg_pset).

It replaces the type of all objects of the target_type with

a generic 'obj' type (or removes them, depending on the specific

abstraction goal - here we rename). It also sets their specific

attribute values to 'UN' (Undefined/Unknown) and

removes tuples containing objects of the original type from

function and relation covers.

A MEMORY field is added/updated in the abstract P-Set (pa_pset)

to store information necessary for potential concretion (drilling down).

Args:

pg_pset (dict): The ground P-Set, structured as:

{'O': [(obj_id, type), ...],

'A': [(obj_id, attr_name, value), ...],

'F': {func_name: [tuple, ...]},

'R': {rel_name: [tuple, ...]},

'MEMORY': {}} # Initial or existing memory field

target_type (str): The type identifier to hide.

Returns:

dict: The abstract P-Set (Pa) after applying the

meth_hidetype method.

(Note: Full memory structure for complex concretion is not fully

implemented here, but the basic structure and data storage are outlined.)

"""

# Start with a deep copy to avoid modifying the original P-Set

pa_pset = copy.deepcopy(pg_pset)

# --- Identify objects of the target type ---

# We need the IDs of objects of the target type to know which

# attributes/tuples to modify later.

# We also store original types for memory/concretion.

objects_of_target_type = [(obj_id, obj_type) for obj_id, obj_type

in pg_pset['O'] if obj_type == target_type]

objects_of_target_type_ids = [obj_id for obj_id, _ in objects_of_target_type]

# --- Prepare memory structure for concretion info ---

# This is a placeholder for storing information needed to

# potentially reverse the process or provide drill-down details.

# In a full KRA model, this structure would be more detailed

# and might handle merging memory from sequential operations.

# For this simple operator, we store the changes it made.

memory_for_this_op = {

'type_changes': [], # Stores (obj_id, original_type) for objects whose type was changed

'attribute_value_changes': [], # Stores (obj_id, attr_name, original_value) for values set to 'UN'

'removed_f_tuples': {}, # Stores {func_name: [removed_tuple, ...]}

'removed_r_tuples': {} # Stores {rel_name: [removed_tuple, ...]}

}

# --- Apply transformations to P-Set components ---

# 1. Modify Objects (O): Change the type of target_type objects to 'obj'

# We build a new list for O in the abstract P-Set.

pa_o = []

for obj_id, obj_type in pg_pset['O']: # Iterate over original O

if obj_type == target_type:

# Change type to generic 'obj'

pa_o.append((obj_id, 'obj'))

# Store the original type in memory

memory_for_this_op['type_changes'].append((obj_id, obj_type))

else:

# Keep objects of other types as they are

pa_o.append((obj_id, obj_type))

pa_pset['O'] = pa_o # Update the O component in the abstract P-Set

# 2. Modify Attributes (A): Set attribute values for objects of the original type to 'UN'

# We iterate through the original A (pg_pset['A']) to capture original values for memory

# and build the new A (pa_a).

pa_a = []

for obj_id, attr_name, value in pg_pset['A']:

if obj_id in objects_of_target_type_ids:

# Set value to 'UN' for objects of the hidden type

# Note: Assumes 'UN' is a valid placeholder for undefined/hidden values

# In a real system, specific handling based on attribute domain might be needed

pa_a.append((obj_id, attr_name, 'UN'))

# Store the original attribute value in memory

memory_for_this_op['attribute_value_changes'].append((obj_id, attr_name, value))

else:

# Keep attributes of other objects as they are

pa_a.append((obj_id, attr_name, value))

pa_pset['A'] = pa_a # Update the A component in the abstract P-Set

# 3. Modify Functions (F): Remove tuples containing objects of the original type

# We iterate through original F covers (pg_pset['F']) for clean tuple checking.

pa_f = {}

# Helper to check if any element in a tuple is one of the target object IDs

def tuple_contains_target_object(tup, target_ids_list):

# Simple check: is element potentially an object ID (by being a string/ID type)

# and is it in the list of target IDs?

# Assumes object IDs in P-Set tuples are represented in a way comparable to target_ids_list elements.

for element in tup:

if isinstance(element, str) and element in target_ids_list:

# Note: This is a simple check. More robust checking might be needed

# depending on the tuple structure and what elements can be object IDs.

return True

return False

for func_name, cover_tuples in pg_pset['F'].items():

pa_f[func_name] = [] # Initialize the list of tuples for this function in pa_f

memory_for_this_op['removed_f_tuples'][func_name] = [] # Initialize memory for removed tuples

for tup in cover_tuples:

if not tuple_contains_target_object(tup, objects_of_target_type_ids):

# Keep tuples that do NOT involve objects of the hidden type

pa_f[func_name].append(tup)

else:

# Remove tuples that DO involve objects of the hidden type

# Store the removed tuple in memory

memory_for_this_op['removed_f_tuples'][func_name].append(tup)

pa_pset['F'] = pa_f # Update the F component in the abstract P-Set

# 4. Modify Relations (R): Remove tuples containing objects of the original type

# We iterate through original R covers (pg_pset['R']) for clean tuple checking.

pa_r = {}

for rel_name, cover_tuples in pg_pset['R'].items():

pa_r[rel_name] = [] # Initialize the list of tuples for this relation in pa_r

memory_for_this_op['removed_r_tuples'][rel_name] = [] # Initialize memory for removed tuples

for tup in cover_tuples:

if not tuple_contains_target_object(tup, objects_of_target_type_ids):

# Keep tuples that do NOT involve objects of the hidden type

pa_r[rel_name].append(tup)

else:

# Remove tuples that DO involve objects of the hidden type

# Store the removed tuple in memory

memory_for_this_op['removed_r_tuples'][rel_name].append(tup)

pa_pset['R'] = pa_r # Update the R component in the abstract P-Set

# --- Update P-Set Memory ---

# The 'MEMORY' key stores abstraction history. Each operation could add

# its specific memory structure keyed by the method name or operator parameters.

# For this example, we add/replace the memory related to this specific operation.

if 'MEMORY' not in pa_pset:

pa_pset['MEMORY'] = {}

pa_pset['MEMORY']['meth_hidetype'] = memory_for_this_op

return pa_pset

Testing meth_hidetype

To test the implementation, we shall create a synthetic example of figures that carry various attributes, similar to examples found in the KRA literature [1].

Figure. Synthetic example: figures ‘a’, ‘b’, ‘c’, ‘d’ with a segment ‘AB’.

We define a simple ground P-Set (ground_pset) based on the structure {'O': [...], 'A': [...], 'F': {...}, 'R': {...}, 'MEMORY': {}}:

# Example Usage

# Define a simple ground P-Set based on KRA Example ideas [1, e.g., 6.3/6.5]

# Assuming object IDs are strings like 'a', 'b', types are strings, attributes are strings/numbers.

ground_pset = {

'O': [('a', 'figure'), ('b', 'figure'), ('c', 'figure'), ('d', 'figure'),

('A', 'point'), ('B', 'point'), ('AB', 'segment')], # Added AB segment

'A': [('a', 'Color', 'green'), ('a', 'Shape', 'triangle'),

('b', 'Color', 'blue'), ('b', 'Shape', 'square'),

('c', 'Color', 'red'), ('c', 'Shape', 'circle'),

('d', 'Color', 'green'), ('d', 'Shape', 'rectangle'),

('AB', 'Color', 'black'), ('AB', 'Length', 10)], # Attributes for AB segment

# Points 'A' and 'B' may not have attributes in this simplified example

'F': {'Center': [('c', 'A')], # Example function cover: Center of 'c' is 'A'. Note: Mismatch with figure 'A'/'B' points for simplicity.

'Radius': [('c', 5)]}, # Example function cover: Radius of 'c' is 5.

'R': {'Rontop': [('a', 'b'), ('c', 'd')], # Example relation covers: 'a' is on top of 'b', 'c' is on top of 'd'

'Rleftof': [('a', 'c')], # 'a' is left of 'c'

'RisPortof': [('A', 'a'), ('B', 'b'), ('AB', 'AB')]}, # 'A' is part of 'a', 'B' part of 'b', 'AB' part of 'AB' segment object itself.

'MEMORY': {} # Initial empty memory

}

print("--- Original P-Set ---")

print(f"O: {ground_pset['O']}")

print(f"A: {ground_pset['A']}")

print(f"F covers: {ground_pset['F']}")

print(f"R covers: {ground_pset['R']}")

print(f"MEMORY: {ground_pset['MEMORY']}")

print("-" * 30)

# Test 1: Target type to hide (e.g., 'point')

target_type_to_hide_1 = 'point'

abstract_pset_1 = meth_hidetype(ground_pset, target_type_to_hide_1)

print(f"--- Abstract P-Set (after hiding '{target_type_to_hide_1}') ---")

print(f"O: {abstract_pset_1['O']}")

print(f"A: {abstract_pset_1['A']}")

print(f"F covers: {abstract_pset_1['F']}")

print(f"R covers: {abstract_pset_1['R']}")

print(f"MEMORY (meth_hidetype): {abstract_pset_1['MEMORY'].get('meth_hidetype', 'Not Stored')}")

print("-" * 30)

# Test 2: Example with another type (e.g., 'figure')

# Apply abstraction again on the *original* ground_pset for a clean comparison

target_type_to_hide_2 = 'figure'

abstract_pset_2 = meth_hidetype(ground_pset, target_type_to_hide_2)

print(f"--- Abstract P-Set (after hiding '{target_type_to_hide_2}') ---")

print(f"O: {abstract_pset_2['O']}")

print(f"A: {abstract_pset_2['A']}")

print(f"F covers: {abstract_pset_2['F']}") # Note: F covers might change if figures were in function tuples

print(f"R covers: {abstract_pset_2['R']}") # Note: R covers now empty as figures ('a', 'b', 'c', 'd') are gone from R tuples

print(f"MEMORY (meth_hidetype): {abstract_pset_2['MEMORY'].get('meth_hidetype', 'Not Stored')}")

print("-" * 30)

# Test 3: Example with a type that doesn't exist (should still run and make no changes except adding memory)

target_type_to_hide_3 = 'car'

abstract_pset_3 = meth_hidetype(ground_pset, target_type_to_hide_3)

print(f"--- Abstract P-Set (after hiding '{target_type_to_hide_3}') ---")

# We expect no changes except for the addition of the 'MEMORY' field for this operation

print("O: (No change)", abstract_pset_3['O'] == ground_pset['O'])

print("A: (No change)", abstract_pset_3['A'] == ground_pset['A'])

print("F covers: (No change)", abstract_pset_3['F'] == ground_pset['F'])

print("R covers: (No change)", abstract_pset_3['R'] == ground_pset['R'])

print(f"MEMORY (meth_hidetype): {abstract_pset_3['MEMORY'].get('meth_hidetype', 'Not Stored')}")

print("-" * 30)

After running the test, the output is:

--- Original P-Set ---

O: [('a', 'figure'), ('b', 'figure'), ('c', 'figure'), ('d', 'figure'), ('A', 'point'), ('B', 'point'), ('AB', 'segment')]

A: [('a', 'Color', 'green'), ('a', 'Shape', 'triangle'), ('b', 'Color', 'blue'), ('b', 'Shape', 'square'), ('c', 'Color', 'red'), ('c', 'Shape', 'circle'), ('d', 'Color', 'green'), ('d', 'Shape', 'rectangle'), ('AB', 'Color', 'black'), ('AB', 'Length', 10)]

F covers: {'Center': [('c', 'A')], 'Radius': [('c', 5)]}

R covers: {'Rontop': [('a', 'b'), ('c', 'd')], 'Rleftof': [('a', 'c')], 'RisPortof': [('A', 'a'), ('B', 'b'), ('AB', 'AB')]}

MEMORY: {}

------------------------------

--- Abstract P-Set (after hiding 'point') ---

O: [('a', 'figure'), ('b', 'figure'), ('c', 'figure'), ('d', 'figure'), ('A', 'obj'), ('B', 'obj'), ('AB', 'segment')]

A: [('a', 'Color', 'green'), ('a', 'Shape', 'triangle'), ('b', 'Color', 'blue'), ('b', 'Shape', 'square'), ('c', 'Color', 'red'), ('c', 'Shape', 'circle'), ('d', 'Color', 'green'), ('d', 'Shape', 'rectangle'), ('AB', 'Color', 'black'), ('AB', 'Length', 10)]

F covers: {'Center': [('c', 'A')], 'Radius': [('c', 5)]} # 'A' is hidden type, but it's a value in F, not an object in the tuple

R covers: {'Rontop': [('a', 'b'), ('c', 'd')], 'Rleftof': [('a', 'c')], 'RisPortof': [('AB', 'AB')]} # ('A','a') and ('B','b') removed as they contain 'point' objects 'A', 'B'

MEMORY (meth_hidetype): {'type_changes': [('A', 'point'), ('B', 'point')], 'attribute_value_changes': [], 'removed_f_tuples': {'Center': [], 'Radius': []}, 'removed_r_tuples': {'Rontop': [], 'Rleftof': [], 'RisPortof': [('A', 'a'), ('B', 'b')]}}

------------------------------

--- Abstract P-Set (after hiding 'figure') ---

O: [('a', 'obj'), ('b', 'obj'), ('c', 'obj'), ('d', 'obj'), ('A', 'point'), ('B', 'point'), ('AB', 'segment')]

A: [('a', 'Color', 'UN'), ('a', 'Shape', 'UN'), ('b', 'Color', 'UN'), ('b', 'Shape', 'UN'), ('c', 'Color', 'UN'), ('c', 'Shape', 'UN'), ('d', 'Color', 'UN'), ('d', 'Shape', 'UN'), ('AB', 'Color', 'black'), ('AB', 'Length', 10)] # Attributes of figure objects are UN

F covers: {'Center': [], 'Radius': []} # Tuples containing 'c' (a figure) are removed

R covers: {'Rontop': [], 'Rleftof': [], 'RisPortof': [('A', 'a'), ('B', 'b'), ('AB', 'AB')]} # Tuples containing 'a', 'b', 'c', 'd' (figures) are removed

MEMORY (meth_hidetype): {'type_changes': [('a', 'figure'), ('b', 'figure'), ('c', 'figure'), ('d', 'figure')], 'attribute_value_changes': [('a', 'Color', 'green'), ('a', 'Shape', 'triangle'), ('b', 'Color', 'blue'), ('b', 'Shape', 'square'), ('c', 'Color', 'red'), ('c', 'Shape', 'circle'), ('d', 'Color', 'green'), ('d', 'Shape', 'rectangle')], 'removed_f_tuples': {'Center': [('c', 'A')], 'Radius': [('c', 5)]}, 'removed_r_tuples': {'Rontop': [('a', 'b'), ('c', 'd')], 'Rleftof': [('a', 'c')]}}

------------------------------

--- Abstract P-Set (after hiding 'car') ---

O: (No change) True

A: (No change) True

F covers: (No change) True

R covers: (No change) True

MEMORY (meth_hidetype): {'type_changes': [], 'attribute_value_changes': [], 'removed_f_tuples': {'Center': [], 'Radius': []}, 'removed_r_tuples': {'Rontop': [], 'Rleftof': [], 'RisPortof': []}} # Memory is added, but empty as no objects of type 'car' were found

------------------------------

Seeing the implemented code and tests for a method makes their operational nature real. meth_hidetype, for instance, doesn’t just conceptually hide a type; it actively modifies the P-Set: relabeling object types to a generic 'obj', setting type-specific attribute values to 'UN', and removing tuples from function/relation covers that involved those objects.

Concretion and Memory

Crucially, the KRA P-Set structure includes a MEMORY component. When a method (meth) runs, it records the details of the transformation it performed. This memory is vital for concretion – the ability to “drill down” from an abstract view back to the underlying details, allowing a user to explore the ground truth that led to the abstract representation.

For example, using the memory_for_this_op stored by meth_hidetype:

- If a user is viewing the abstract P-Set (Test 2, hiding ‘figure’) and sees object

'a'is of type'obj'and has attribute('a', 'Color') = 'UN', they could consult the memory under'meth_hidetype':- Look up

'a'in'type_changes'to find its original type was'figure'. - Look up

('a', 'Color')in'attribute_value_changes'to find its original value was'green'.

- Look up

- If they wonder what relations

'a'was involved in before the abstraction, they could check'removed_r_tuples'for relations where'a'appeared, finding tuples like('a', 'b')in the original'Rontop'relation cover.

This ability to navigate between the abstract and concrete views, facilitated by the structured MEMORY, is powerful for analysis and understanding complexity without being overwhelmed. This roundtrip capability is essential in practical reverse engineering scenarios.

More Operator Examples (Conceptual)

Beyond hiding, KRA operators offer diverse transformations:

- Equating (

ωeq...): Imagine usingωeqattrvalon the E-commerce P-Set’slatencyattribute. Instead of12.5,35.1, etc., you could equate values within ranges (e.g.,[0, 50]to ‘Low’,[51, 100]to ‘Medium’). Themeth_eqattrvalwould modify the ‘A’ component, replacing specific latency values with these abstract categories for the relevant services. - Combining (

ωgroup): Using the E-commerce P-Set, you could applyωgroupwith a condition to group services and databases that are “part of the Order fulfillment process” (e.g., ‘OrderService’, ‘InventoryService’, ‘OrderDB’).meth_groupwould create a new abstract object in ‘O’ representing this group (e.g., ‘OrderFulfillmentComponent’), and potentially new aggregated attributes, functions, and relations in ‘A’, ‘F’, and ‘R’ summarizing the grouped elements. - Hierarchy (

ωhier...): On the figures example,ωhiertypecould group ‘triangle’, ‘square’, ‘circle’, ‘rectangle’ under a parent type ‘Polygon’ or ‘Shape’.meth_hiertypewould update the ‘O’ component to reflect this hierarchy, potentially allowing relations to be defined on the abstract ‘Shape’ type.

These examples illustrate how different operators, acting on the P-Set, enable various forms of abstraction, each serving a specific purpose related to a Query (Q).

In Reverse Engineering

This structured, operational approach is incredibly valuable when applied to real-world problems involving significant complexity, such as software system analysis via reverse engineering [2, 3]. Reverse engineering tools produce a fire hose of data about classes, methods, dependencies, configurations, and more. This output is our Ground P-Set ($P_g$) and potentially other data structures. The challenge is to make this immense detail understandable for specific analysis tasks (Queries $Q$) like understanding architectural dependencies, identifying refactoring candidates, or analyzing security flaws.

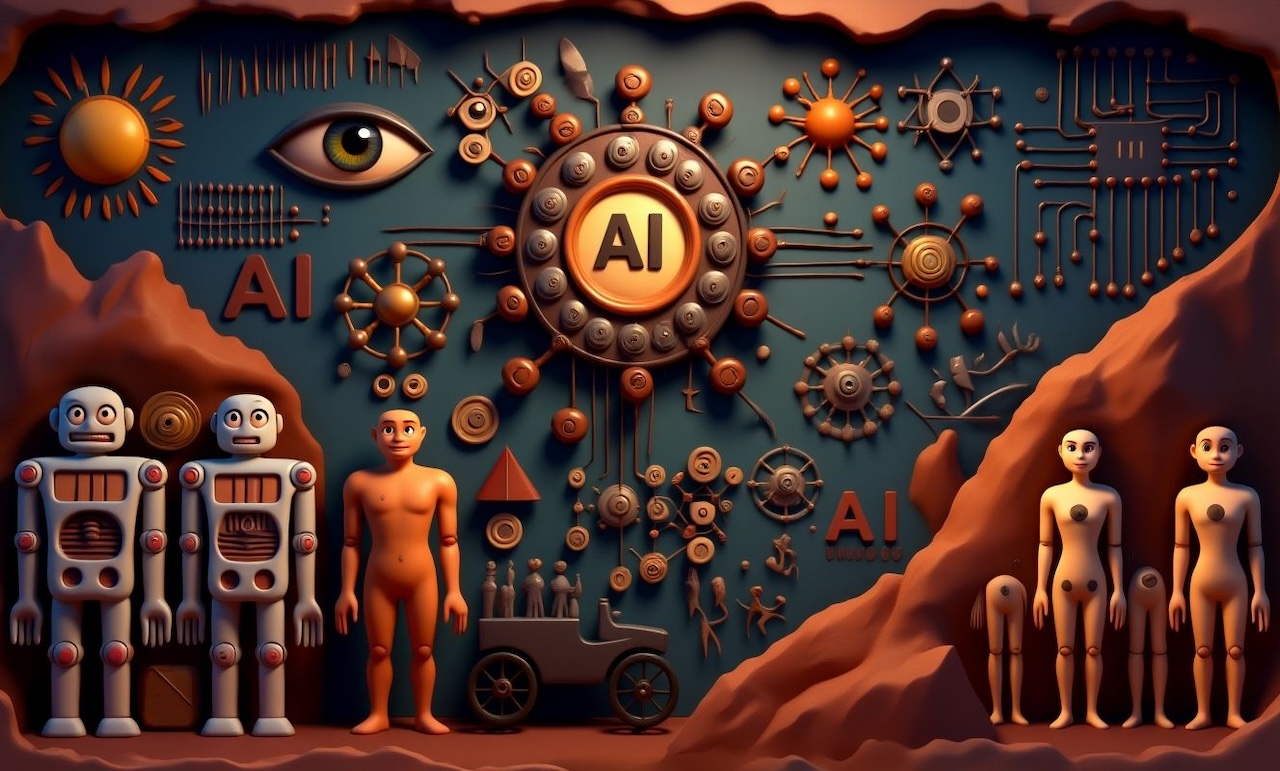

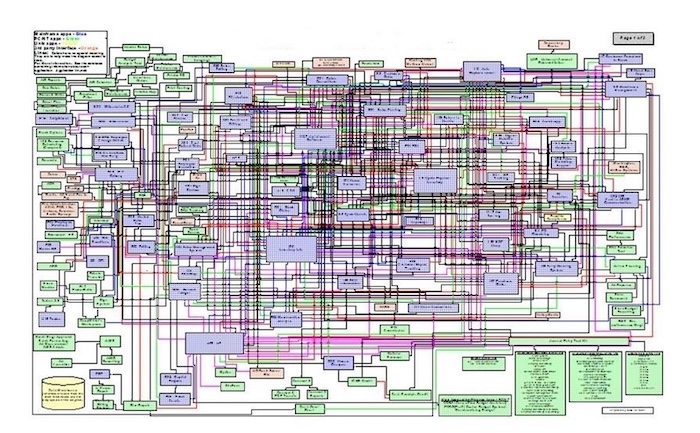

Figure. A Visual Illustration of IT System Complexity. This diagram exemplifies the overwhelming intricacy often found in large-scale IT systems. With hundreds of interconnected components, it highlights how low-level system representations can become nearly indecipherable—underscoring the need for abstraction and high-level modeling to manage and reason about such complexity effectively. (Note: Image quality is low in source: https://rickrobinson.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/it-systems.jpg)

KRA operators provide the systematic tools for this. We can use:

- Hiding (

ωh...): To clear away the noise – hiding private methods, specific attribute values (like line numbers), or low-level dependencies irrelevant to the current query. - Equating (

ωeq...): To simplify the vocabulary – equating different collection types, grouping error codes into categories, or treating specific DTO instances as a single concept for a particular analysis. - Hierarchy Generating (

ωhier...): To build architectural views – grouping classes into components (often working withωaggrorωgroupfor Combining), creating abstract attributes for modules (like stability or churn derived from file changes), or defining inter-component relations derived from class-level calls. - Combining (

ωcoll,ωaggr,ωgroup,ωconstr): To explicitly group elements – aggregating classes into services, grouping files by ownership or sprint, or constructing new relations from existing ones (e.g., ‘ServiceA_depends_on_ServiceB’ derived from multiple class-level dependencies). - Approximating (

pid...,prepl): To simplify attribute ranges or element types where some precision can be sacrificed for clarity – replacing specific version numbers with categories (‘major’, ‘minor’), or large sets of objects with a representative sample.

Using a formal model like KRA for this offers distinct advantages over ad-hoc scripting. It’s operational and repeatable. It encourages capturing reusable abstraction patterns. The built-in memory and concretion capability allows drilling down, providing necessary context without overwhelming the initial view. It’s a principled, structured approach that helps ensure abstractions are meaningful and fit for purpose, even providing a way to handle inconsistencies inherent in real-world systems.

Leveraging AI within the KRA Framework

This brings us to the exciting prospect of leveraging AI within the KRA framework. KRA gives us the what (the operators) and the how (the methods to apply them to the P-Set). AI can tackle the which and the when – deciding which specific operators, with which parameters, to apply in what sequence to best address a user’s query (Q) on a complex system representation ($DS_g$, effectively our $P_g$).

AI can first assist in the initial structuring of raw reverse engineering output into the KRA components ($O_g, A_g, F_g, R_g$). More significantly, AI can learn abstraction strategies. Given a user’s query (Q) and the ground P-Set ($P_g$), the goal is to produce a relevant abstract P-Set ($P_a$).

- Learning Operator Selection: Supervised learning can train models on examples of how expert architects or analysts successfully abstracted similar systems for similar tasks. The AI could learn to map characteristics of the query (Q keywords, analysis goal) and features of the $P_g$ (number of objects of certain types, density of relations, value ranges of attributes) to sequences of KRA operators and their parameters. Decision trees, rule learning systems, or even sequence-to-sequence models could potentially be used.

- Optimizing Abstraction: Reinforcement learning can allow an AI agent to explore the vast space of possible operator applications. Given a Q, the agent receives a reward based on metrics quantifying the quality of the resulting $P_a$ (e.g., size reduction, relevance to Q, clarity of structure, navigability via memory). The agent learns policies for applying operators sequentially to maximize this reward.

- Parameter Discovery: AI techniques like clustering or pattern mining can automatically discover useful parameters for operators. Clustering objects in $P_g$ based on their attributes or relations can suggest groups for

ωeqobjorωgroup. Analyzing attribute value distributions can inform parameter choices forωhattrvalorωeqattrval. Identifying common graph patterns in F or R covers can suggest candidates forωconstr. - Workflow Adaptation: Case-based reasoning can store and adapt past successful abstraction workflows (sequences of operators with parameters) for similar queries or system structures.

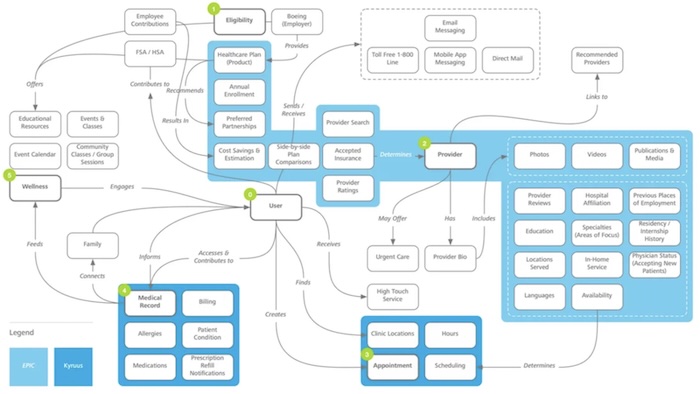

Figure. Abstracted View of an IT Healthcare System: as an illustration, a user-centered abstraction of a complex healthcare IT ecosystem. By applying AI-driven abstraction operators—such as grouping related functions (ωgroup), hiding low-level technical details (ωh...), and highlighting key user flows—the system becomes comprehensible at a glance. It illustrates how abstraction transforms overwhelming technical complexity into an intuitive, actionable map that supports clarity, navigation, and decision-making. (image source: Christina Wodtke [5] (http://architecture.31bio.org/information-architecture-concept-model/))

This vision culminates in an AI-powered KRA workbench – an integrated platform connecting reverse engineering tools to a KRA representation. The AI component interprets the user’s query and the system structure ($P_g$), then recommends or automatically applies sequences of KRA operators. It executes the corresponding methods on $P_g$, producing a simplified $P_a$. The user interacts with this abstract view, and the platform, using the KRA memory, facilitates drilling down into details as needed. The system learns from the user’s feedback and interactions, refining its abstraction recommendations over time.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the feeling of being swamped by complexity is pervasive. Abstraction is our most powerful tool for distilling essence from superficial trappings, making the incomprehensible manageable. The KRA model [1] provides a rigorous, operational framework with defined operators and methods for performing this abstraction on observable data (the P-Set). By leveraging AI – through machine learning, clustering, pattern recognition, and intelligent recommendation systems – we can automate and optimize the selection and application of KRA operators based on user queries and the underlying data. This synergy of the formal KRA structure and the learning power of AI holds immense potential to fundamentally change how we analyze and interact with large, complex systems, not just in software reverse engineering [2, 3], but potentially in any domain where drinking from the fire hose of raw detail prevents true understanding. The question for us is, what essence do we need to distill from the complexity around us?

References

- Saitta, Lorenza, and Jean-Daniel Zucker. Abstraction In Artificial Intelligence And Complex Systems. Springer, May 2013. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7052-6_1

- This book presented a model of abstraction, the KRA (Knowledge Representation & Abstraction) model, but this is not the core of the book. It has a limited scope and serves two main purposes: on the one hand it shows that several previous proposals of abstraction theories have a common root and can be handled inside a unified framework, and, on the other, it offers a computational environment for performing abstraction by applying a set of available, domain-independent operators (programs).

- Paolo Tonella, Marco Torchiano, Bart Du Bois Tarja Systä, Empirical studies in reverse engineering: state of the art and future trends, Empir Software Eng, Springer, 2007. DOI 10.1007/s10664-007-9037-5.

- Starting with the aim of modernizing legacy systems, often written in old programming languages, reverse engineering has extended its applicability to virtually every kind of software system. Moreover, the methods originally designed to recover a diagrammatic, high-level view of the target system have been extended to address several other problems faced by programmers when they need to understand and modify existing software. The authors’ position is that the next stage of development for this discipline will necessarily be based on empirical evaluation of methods. In fact, this evaluation is required to gain knowledge about the actual effects of applying a given approach, as well as to convince the end users of the positive cost-benefit trade offs. The contribution of this paper to the state of the art is a roadmap for the future research in the field, which includes: clarifying the scope of investigation, defining a reference taxonomy, and adopting a common framework for the execution of the experiments.

- Tonella, Paolo, and Alessandra Potrich. Reverse Engineering of Object Oriented Code. Vol. 1. Springer, 2005.

- The algorithms described in this book deal with the reverse engineering of the following diagrams: Class diagram, Object and interaction diagrams, State diagram, Package diagram. (Descriptions omitted for brevity, but available in the source).

- Robert, Goldstone and Lawrence Barsalou, Reuniting perception and conception, Cognition 65 (1998) 231–262

- Work in philosophy and psychology has argued for a dissociation between perceptuallybased similarity and higher-level rules in conceptual thought. Although such a dissociation may be justified at times, our goal is to illustrate ways in which conceptual processing is grounded in perception, both for perceptual similarity and abstract rules.

- Christina Wodtke, Five Models for Making Sense of Complex Systems, Medium, 11 Feb 2017

- Introduces five visual frameworks to help individuals and teams navigate and understand complex systems. These models serve as tools for both exploration and communication, facilitating a deeper understanding of complex systems through visual thinking.

- Ruixin Hong, Hongming Zhang, Xiaoman Pan, Dong Yu, Changshui Zhang, Abstraction-of-Thought Makes Language Models Better Reasoners, arXiv:2406.12442 [cs.CL], 18 Jun 2024.

- Abstract reasoning, the ability to reason from the abstract essence of a problem, serves as a key to generalization in human reasoning. However, eliciting language models to perform reasoning with abstraction remains unexplored. This paper seeks to bridge this gap by introducing a novel structured reasoning format called Abstraction-of-Thought (AoT). The uniqueness of AoT lies in its explicit requirement for varying levels of abstraction within the reasoning process. This approach could elicit language models to first contemplate on the abstract level before incorporating concrete details, which is overlooked by the prevailing step-by-step Chain-of-Thought (CoT) method. To align models with the AoT format, we present AoT Collection, a generic finetuning dataset consisting of 348k high-quality samples with AoT reasoning processes, collected via an automated and scalable pipeline. We finetune a wide range of language models with AoT Collection and conduct extensive evaluations on 23 unseen tasks from the challenging benchmark Big-Bench Hard. Experimental results indicate that models aligned to AoT reasoning format substantially outperform those aligned to CoT in many reasoning tasks.